BY ALEX EBRAHIMI | On a clear day, the song says, you can see forever. In the Village, you’ll see Kazuya “Kaz” Morimoto.

“My work is about question and answer,” he told me at his West 11th Street studio on a clear, albeit short day in late November.

As he picked out a sketchbook from the shelf, I asked, “Why the Village?”

Checking the year written on the binding, he said, “Still waiting for the answer.”

“Well, what’s the question?”

“How long is it going to last?” he said flipping through the pages.

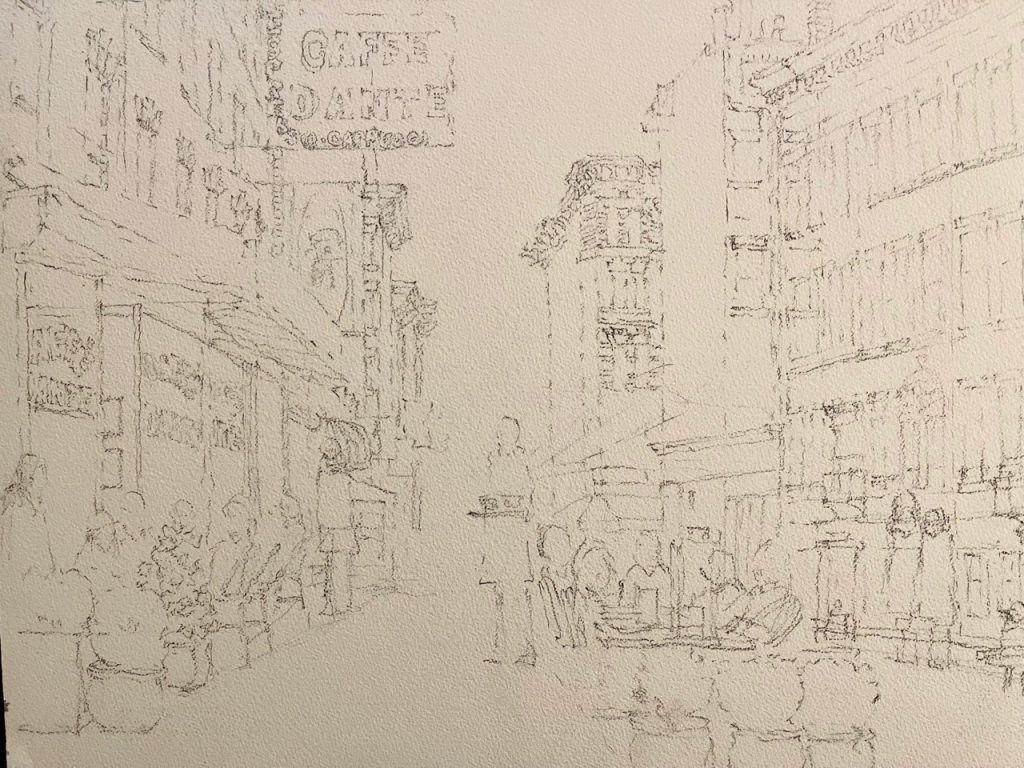

Distracted by two unfinished watercolors of the Caffé Dante at two different angles, I asked, “How long does it take you to finish a painting?”

“That one’s taken years… .”

Setting up doesn’t take long. Watercolor paper clipped to a board on his lap. Legs crossed into a makeshift easel. Prints of his other paintings for sale around him. He sits where he paints and paints where he sits.

Before the brush, he sketches in pencil. Once he’s got the graphite skeleton of the scene, he’s ready to paint. But today’s painting is one he’s returning to. It’s almost there. It’s just a matter of the Caffé Dante. The waiter who never smiles is waiting to be painted. But Dante…Dante…where’d it go?

It’s Dante he sketched the other day, not the scaffold that’s there now. Even the waiter who never smiles started wearing a mask.

But as long as the day’s clear, he’ll keep on painting. From MacDougal Street, he packs up his palette and trade for a backup location: Sheridan Square.

There’s something about water towers in this town. But the day’s too short to find the right words. And realizing now that the water tower’s too tall, he erases it. Trying again. Once he’s got it, he picks up the brush when…

An old woman wearing a white fur coat screeches her walker nearer to ask: “Where’s the bar?”

He checks the painting, then the square itself. No bar. Not even a scaffold.

“Are you sure?” he asks.

“Of course,” pointing to where it should be in the painting, “I had my first date with Steve McQueen at that bar!”

People come and go as he paints. Dog walkers. Stroller pushers. Stopping now and then. To watch. To talk. Many recognize him. Even abroad. Filling sketchbook after sketchbook of European summers in black ink.

If painting the Village taught him anything, it’s the coming and the going. Of people. Of buildings. Tourists along 14th. Zoning around Noho. The Bowery isn’t what Reginald Marsh painted. And what remains of Art Deco is just the echo.

The Village is a town at low tide. Like the shipyard Kaz once painted in Cornwall, England. Starting with a sketch of a boat on stilts, returning to find the boat afloat.

Not the first time the English Channel’s interfered with the creative process. Monet was nearly swept away by the rising tide while painting the Normandy coast on the other side.

Not the last time a painter was nearly swept away by the rising tide. Looks like the landlord’s selling the W. 11th Street studio. But Monet didn’t drown. And there’s always the studio on the Upper West Side Kaz keeps for storage.

But the day’s too short to worry about drowning in the English Channel. The day’s too short…and now the wind. A homeless man pushing his shopping cart down W. Fourth Street howls back, “Moooore wind please! Moooore wind please!” Kaz calls it a day.

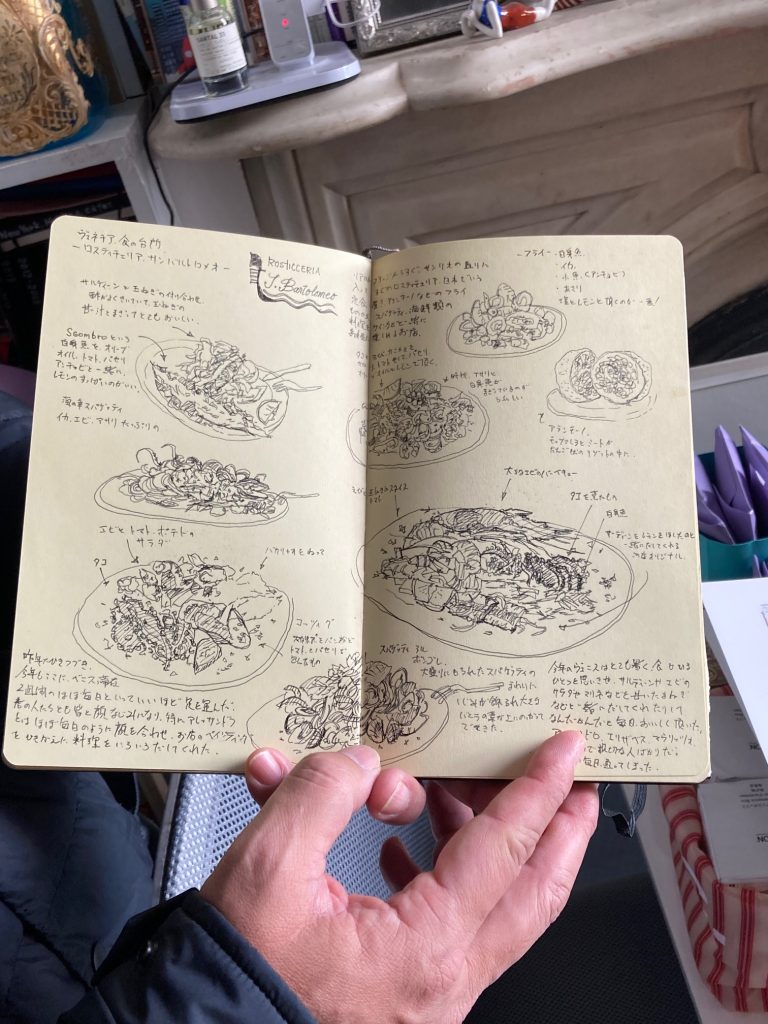

“I don’t know why,” he says showing me that sketchbook he took from the shelf, “but I’m nostalgic about Venice.”

At the top of the first page he’s written the Italian “Venezia.” Under it, and for the rest of the sketchbook, all the sketchbooks of his European summers, his observations are written in Japanese. Justifying the juxtaposition he said, “otherwise I’ll forget Japanese.”

“How many years has it been since you left Japan?” I ask, as he turns to a sketch of Vittore Carpaccio’s Lion of St. Mark.

“Twenty years,” he says, turning page after page.

Distracted by a spread covered with sketches of various dishes from his favorite rosticceria in Venice, I ask, “Doesn’t it get cold?”

“Cold?” he asks, as he finally stops turning the pages.

“The food!”

“Oh!” he laughs as he goes on turning the pages.

“By the time you finish drawing your lunch, it must be dinner,” I quip.

Like impressionist paintings, Kaz’s watercolors are of clear days. And like the impressionist period, there’s nothing forever about them.

The phrase “a place in the sun” sounds like the title of an impressionist painting. And that’s just how it was. The competition didn’t allow any one painter his or her “place in the sun.” And that’s just how it decayed.

With painters like Gauguin it wasn’t just the competition that didn’t allow him his place in the sun, but the rising tide of industrialization. That’s why he found his place in the sun in Tahiti, the place farthest from the shores of the civilized, technological world.

With Kaz it wasn’t just the conservatism of the Japanese countryside that sent him away, but the social Darwinism of how to make it as an artist in Japan. The school you had to attend. The circle you had to join. The exclusivity of it all. The competition.

But Kaz found his Tahiti in the middle of what Gauguin was trying to get away from. A place at low tide. That’s why he brings more than one painting out on a day’s work. It’s rarely one location. Setting up can’t take long. The summers are too hot. And now, the days are too short. But the sunset isn’t always to blame. Lately, it’s just a matter of the Caffé Dante.

When he exhibits his work in Europe, now and then they don’t even recognize the New York he’s painted. They expect the rising tide of glass, not the coral reef being swallowed. They call him Kaz. They should call him the almanac painter.

Nice blog, keep it up.