BY DASHIELL ALLEN | In an effort to challenge the developer-funded status quo, 41 teams of architects from across New York City submitted proposals this spring to reimagine 5 World Trade Center as a 100 percent affordable high-rise tower.

Last month, on a rainy Saturday evening at The Clemente Cultural Center on the Lower East Side, architects and designers presented their proposals to housing activists in the Coalition For a 100 Percent Affordable Tower Five.

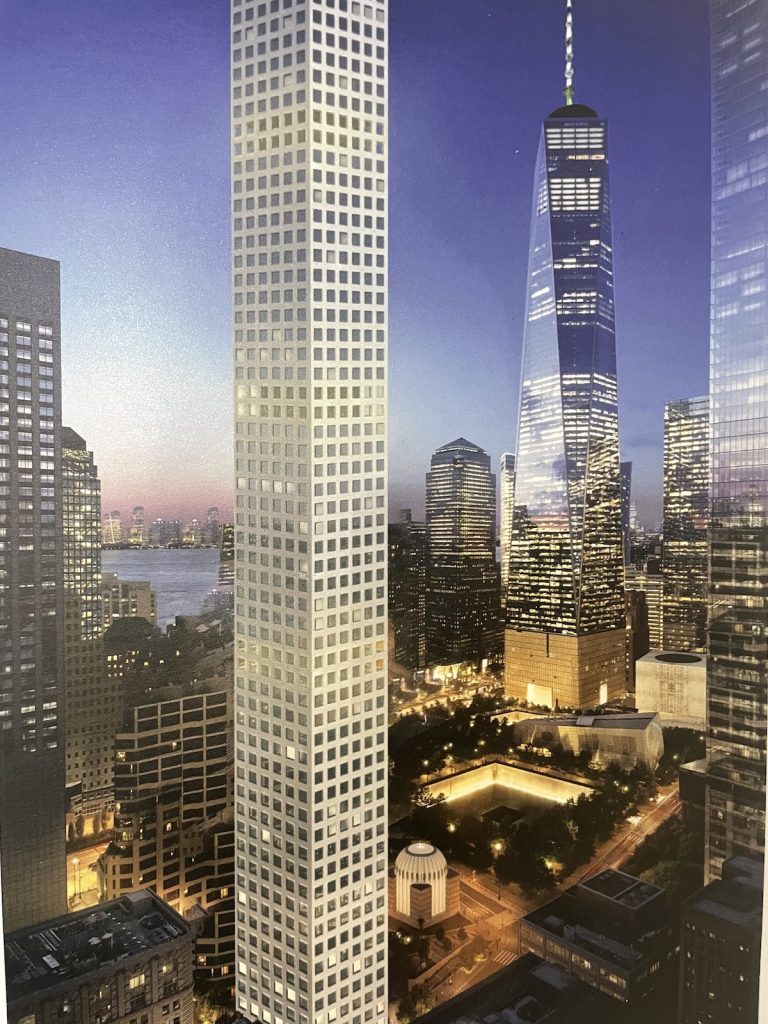

The last publicly owned, undeveloped site in the World Trade Center campus, the Port Authority and Lower Manhattan Development Corporation plan to build an 85-story residential tower with 75 percent luxury and 25 percent affordable housing at 5 World Trade Center.

Last year, in a closed request for proposals (R.F.P.), the two entities announced a single design, funded by developers Brookfield and Silverstein Properties. City Group, an activist architecture collective, however, decided to have more fun with the idea.

Their alternative design competition, developed in conjunction with the New York Review of Architecture, was based on the competition to design Chicago’s Tribune Tower in the early 20th century, as well as the original World Trade Center competition shortly after 9/11.

The former, which featured styles ranging from Art Deco to neo-Gothic and factory-inspired design, submitted by more than 260 architects from 23 countries, remains a pivotal moment in the history of architecture.

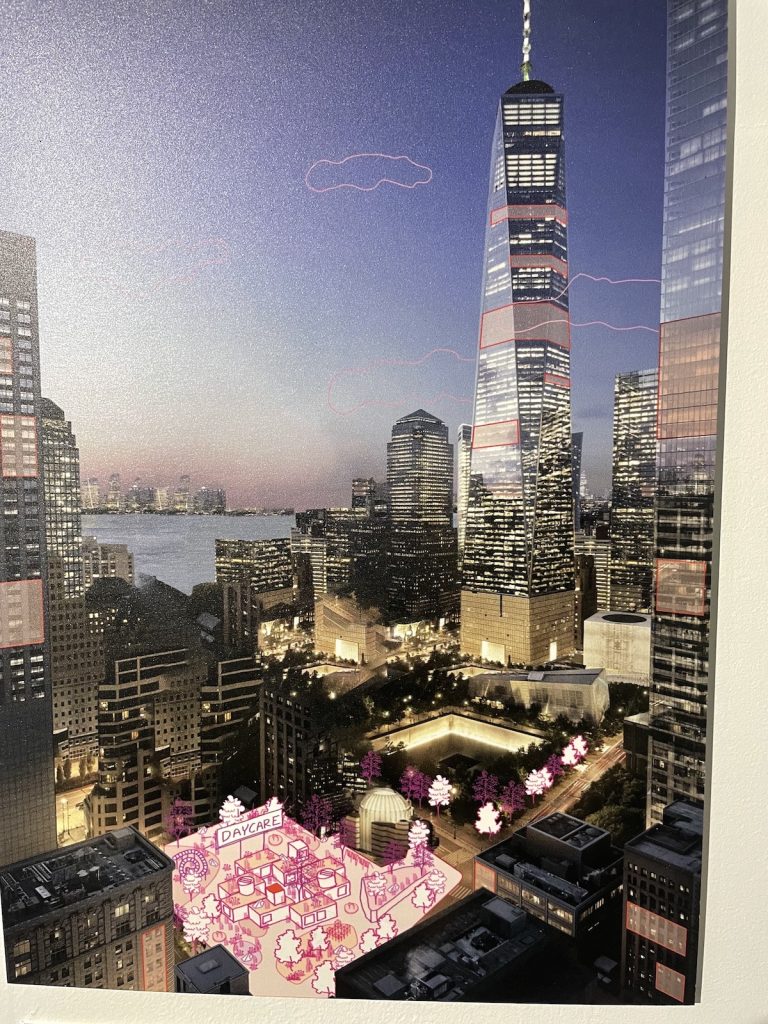

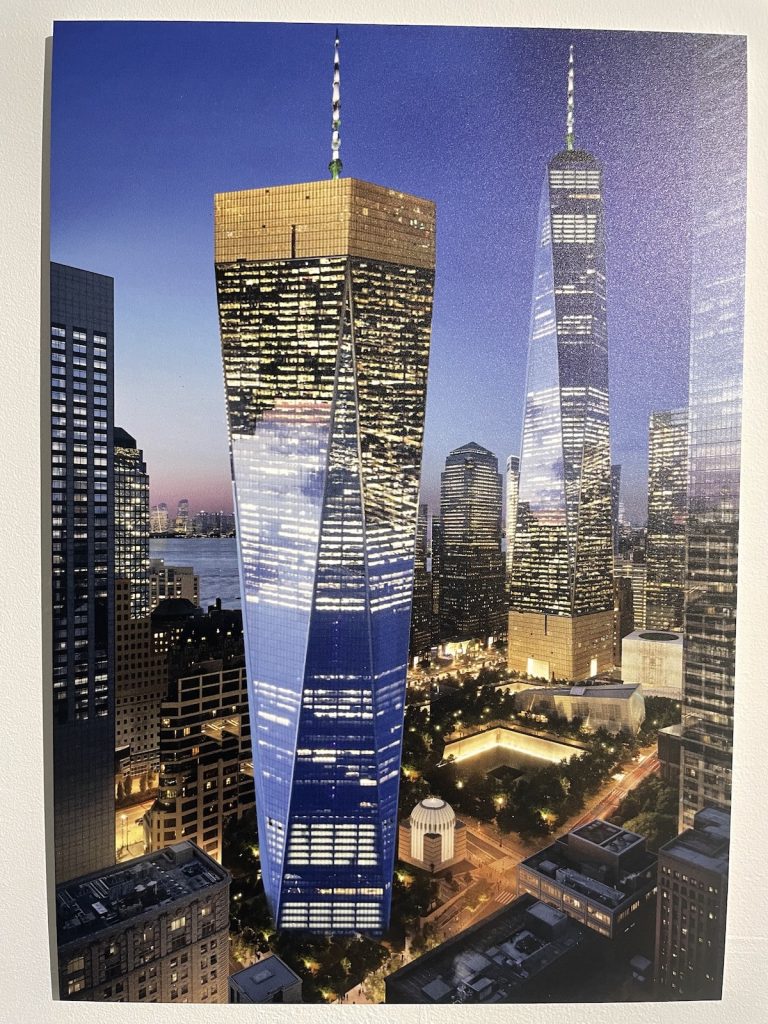

Throughout May, glossy renderings, similar to the ones posted at construction sites, adorned the walls of City Group’s gallery space on Forsyth Street. But while presenting at The Clemente, many architects expressed skepticism that design has any influence on the economics of building buildings.

“Architects cannot save New York City through architecture,” said Nile Greenberg, from the firm ANY. “The heroics of architecture often lead to disastrous decisions. The insistence from a lot of architects that the question of design is part of the question of affordability is a bit of a red herring. There’s something missing from that question, and distracting us from the policy and origination of these projects.”

His proposal was simply an empty box in the space of an affordable tower, as he put it, “resisting any imagination by an architect to insist that policy comes first.”

Another architect, Brad Isnard, described his design as “more or less arbitrary.” It was based around a social-housing development in Paris.

“We want to make a stand as architects, and not allow our project to be used to launder brutal austerity measures for us, while spending without care on these massive corporate investment projects, but provide a kind of earnest vision for a future that we all want to share and fight for,” he said. “The message is the same that it’s always been: that the costs are to be borne by the city and by the public, and the profits become private.”

In this case, Isnard pointed out, the state had already spent $250 million on acquiring and clearing the site. In their entirety, Forbes estimated last year the value of the World Trade Center campus’s skyscrapers to be $11 billion, including $3.3 billion in debt to tax-exempt Liberty Bonds.

Why, then, housing advocates ask, should the only residential building on the campus be forced to make a “profit” through luxury housing?

Lane Rick of the architecture and design studio Office of Things proposed placing an existing supertall “pencil tower,” 432 Park Ave., in the place of 5 World Trade Center.

Rising 96 stories at E. 57th Street, the tower contains a meager 104 units. In fact, Rick pointed out, “432 Park actually houses fewer people than the midrise buildings that it replaced.” (As The New York Times reports, however, life in 432 Park is not all it’s cracked up to be.)

Rick posited that, if reconfigured, the same structure could hold upward of 750 units.

“It’s actually something you could use to rethink every single other pencil tower through the city skyline across Billionaires Row,” she said. “You can recast this towering symbol of excess into a powerful symbol of affordability and resourcefulness.”

Architect Marc Wouters suggested that building slightly shorter — up to 60 stories — would allow the developers to save on the cost of more-expensive structural systems, accounting for higher wind loads and other maintenance fees.

There were some very unique proposals.

“Design optimization is the poisoned legacy of Christianity,” posited another entry, made by the anonymous practicing critic Dank Lloyd Wright.

“Rather than make design more affordable, we should elevate the human closer to God and design our buildings to worship Her perfection,” they said, proposing to place a giant statue of Julia Fox in the place of a tower.

All jokes aside, the central question was: What is the role of architecture to critique or challenge the economic superstructure of development? To many speakers at The Clemente, doing so appeared like a worthwhile goal, albeit incredibly daunting.

The answer to that question, and how the existing dynamic could change, has as much to do with the labor practices of the architecture industry as it does with the economics of development itself.

Andrew Daley was a practicing architect for more than a decade. At the beginning of 2021 he became a full-time organizer for the Machinists Union. During his time working in the profession, he began to realize that a large part of what was expected of him didn’t line up with the education he had received.

“We’re not taught business in school,” he said. “We take one professional-practice class, and most of them honestly are just an old white dude who was a principal at a firm for a long time, bringing in his buddies to tell war stories.”

According to Daley, architects are often required to work long, uncompensated, overtime hours — up to 80 hours per week on rare occasions. That’s at least in part because of development pressures.

When a developer or government agency releases an R.F.P., they typically expect to receive proposals without compensation to the submitters. While there often aren’t set guidelines for how much work is required for an R.F.P., since architecture and design firms are competing against each other, they would logically work as hard as they could to present the best thought-out designs and renderings.

Due to two antitrust cases brought against the American Institute of Architecture (A.I.A.), there’s also no standard fee and wage structures set for the industry, or between developers and clients. Ultimately, those are just some of the structural issues that have led to a push for unionization in the industry.

Last year, architects at SHoP, one of the most prominent architecture firms in New York City, responsible for designing Barclays Center, Essex Crossing, the tallest tower in Brooklyn and much more, attempted to form a union, only to be foiled in February 2022, citing a “powerful anti-union campaign.”

A shared recognition of desperately needed reforms in the industry has also led to the formation of the Architecture Lobby, a decentralized nationwide organization of which Daley is also a member.

A manifesto on the Architecture Lobby’s Web site lists some of its demands: “Build worker power and collective agency through unions and cooperatives; A living wage, benefits, job security, and wage transparency across the discipline; Fight for democratic alternatives to the capitalist system of development.”

Daley believes that the collective power of architects — when they recognize themselves as a unified workforce — has the potential to transform not just their working conditions but the industry itself.

“I think collective action around these things is what’s important,” he said of demands like 100 percent affordable developments. “I think architects have that ability, but it’s really hard to do it on an individual disparate basis. What it requires is massive organizing and that’s what unionization is really about.

“Once you’re together in that collective, what other things can we organize around? And I think that’s a powerful thing that unions make clear. This other issue — whether it’s abortion or immigration — those are labor rights, as well and we need to organize around those just as much as we need to organize around collective bargaining rights.”

And there is precedent for architects to make such demands as 100 percent affordability. For instance, in 2020 the New York chapter of A.I.A. issued a statement “calling on architects no longer to design unjust, cruel or harmful spaces of incarceration within the current United States justice system, such as prisons, jails, detention centers and police stations.”

“If we can make that kind of stance, why can’t we make other stances?” Daley asked.

Architects Violette de La Selle and Michael Robinson Cohen, the co-founders of CityGroup, agree.

“The economics of this particular site are completely out of whack,” de La Selle said of 5 World Trade Center. “Because the site is free, so is the cost of construction. And if the city says you can only build here if you provide 100 percent affordable housing, then they’re going to find a way to make it viable.”

“Architects are realizing their power as workers and their ability to actually form unions,” Cohen said. “At the same time, I think the way in which architecture has been practiced for so many years works against that. Architects do feel like they’re competing against each other for projects, and they have to devalue their skills and undervalue how much they charge clients in order to get jobs. So there are a lot of forces that are eroding the potential collective consciousness.”

“I feel like housing and affordable housing,” Cohen said, “is this force that can bring together so many people across the city into a popular movement.”

“Why, then, housing advocates ask, should the only residential building on the campus be forced to make a ‘profit’ through luxury housing?”

Weird statement. What “housing advocates” are saying this? Also seems to imply that if you take out the profit the housing could be affordable without subsidy, which is not the case. Also seems to imply that the office buildings don’t have to be economically viable, which isn’t true. They got subsidies including the tax-exempt bonds, but they have to pay those back and a lot of additional private money went into the office towers, which is being recovered through commercial rent.

It really warms my heart to read about architects with a conscience actually mobilizing for justice and housing and equity. Thank you for this article.

I thought the comment from Nile Greenberg was notable and worth thinking about:

“Architects cannot save New York City through architecture. The heroics of architecture often lead to disastrous decisions. The insistence from a lot of architects that the question of design is part of the question of affordability is a bit of a red herring. There’s something missing from that question, and distracting us from the policy and origination of these projects.”

Glad the article included that.