BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Coss Marte is the type of cannabis store operator that the city and state want to support. After getting his dispensary license about a year ago, he opened CONBUD last November at Delancey and Orchard Streets. It’s a great location — high foot traffic, and you can’t miss his big green-and-white awning on the corner.

A Lower East Side kid, Marte used to deal big time just a few blocks away from where his store stands today — and wound up doing time for it. As a criminal justice-involved applicant, he was among the first round of operators prioritized to get a dispensary license from the state’s new Office of Cannabis Management.

But even with a coveted cannabis license in hand, at first he wasn’t able to make the kind of profits he should have been making — because of the gray market, the thousands of unlicensed pot shops that have sprung up after New York State legalized weed three years ago. There were dozens of them near his place and they all operated with fewer restrictions — and more cheaply — than he could. (By contrast, there are currently only around 100 legal weed stores statewide, and more than 40 in New York City.)

Just one example, the illicit shops sport bright signage and colorful neon lighting to better lure in customers, whereas the legal stores’ exteriors are supposed to be more discreet. And, of course, by not paying state taxes on their product or having to sell New York-grown herb, their goods are less expensive.

In short, according to one cannabis insider who knows him well, at first Marte’s pot business “was hurting.”

New enforcement

But the wind has shifted against the illegal stores as Governor Hochul and Mayor Adams are flexing new enforcement power. In May, Adams launched Operation to Padlock to Protect to shutter the outlaw outlets.

“With these new enforcement powers and legal authority granted by the state,” Adams declared, “we are making it clear that any operator acting illegally will face swift consequences as we protect our city’s children, improve quality of life and facilitate a safe and thriving legal cannabis market.”

In its first month, the city’s new effort shut down 300 of the unlicensed shops. Meanwhile, the state’s new Cannabis Enforcement Task Force closed 100.

“We are committed to building the strongest, most equitable cannabis market in the nation,” Hochul said. “In order to advance that goal, we promised to expedite the closure of unlicensed cannabis storefronts, and I’m here today to say: We’re getting it done.”

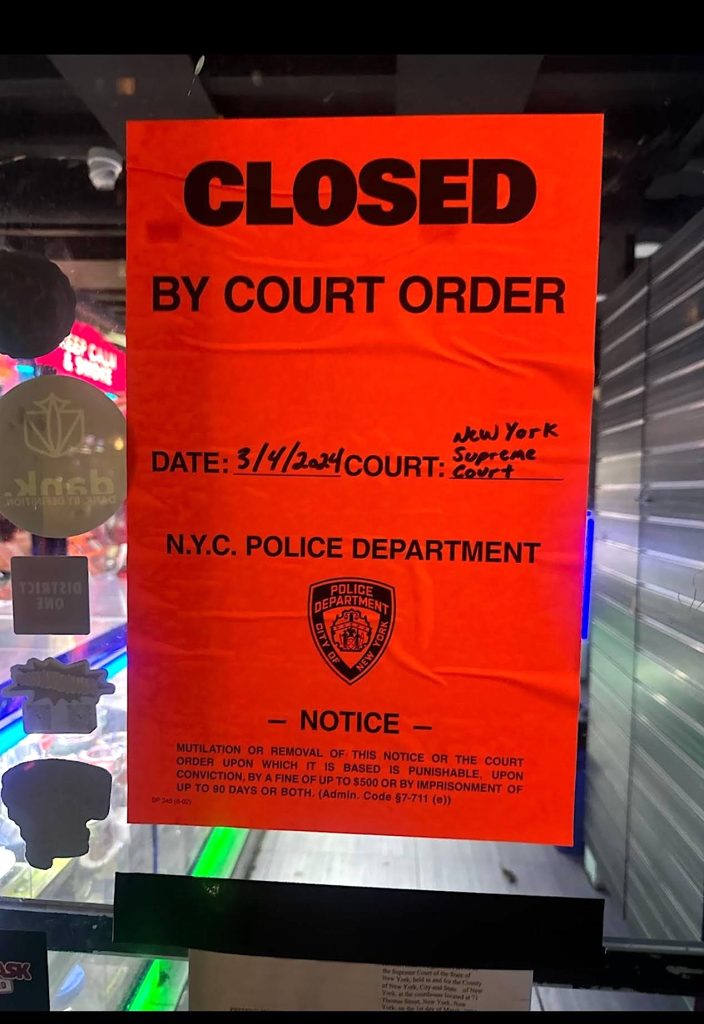

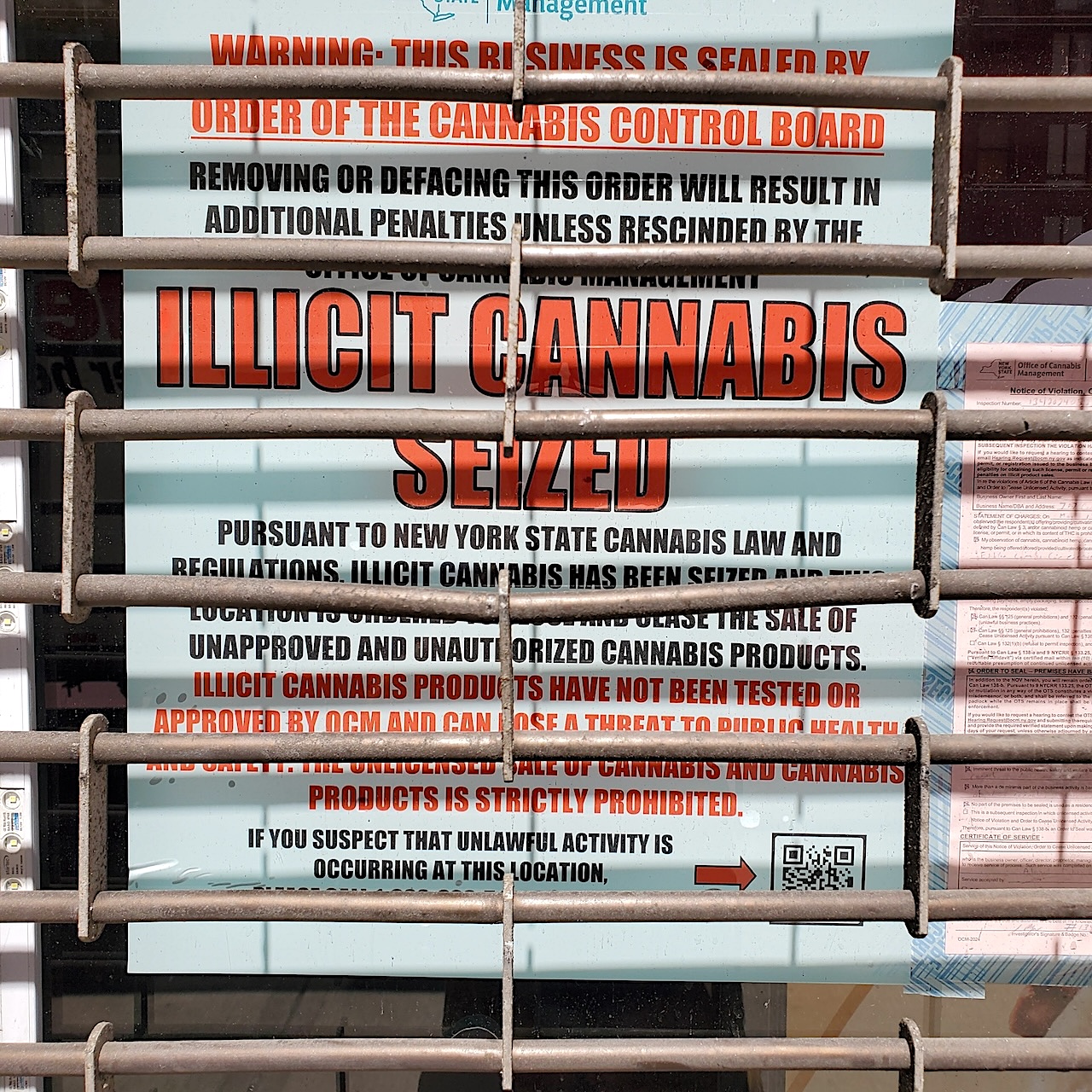

The effects on the street have been noticeable, with many rogue reefer places now shuttered and with stickers slapped on their doors and windows declaring they are closed and sealed. Merely removing one of the stickers can result in a fine of $500 and 90 days in jail. Around four different enforcement agencies are said to be conducting the shutdowns.

The Lower East Side alone has nearly three dozen gray-market ganja shops, and some of these operators are refusing to go down easy. In one recent case, the owners of a shuttered Stanton Street smoke shop with a red “CLOSED” sticker on their glass front door, rather than peel off the adhesive, simply smashed the whole thing out — and installed new glass.

The chips trick

As recently reported in The New York Times, a group of LES activists have diligently been keeping a Google spreadsheet tracking which illegal pot shops are open and closed in their neck of the woods. One of them, who spoke to The Village Sun on condition of anonymity for her safety, is adamant the new crackdown simply is not all that it’s cracked up to be.

“We have a store mentioned in the Times article that reopened in barely a week — removed their signs and reopened,” she said. “Many businesses that are selling have taken the products off the shelf and replaced them with chips. This is factual on the LES — back to what it was initially, i.e. under-the-counter sales with chips on the shelves, product not out in the open. You can’t pay $15,000-a-month rent selling chips — and it’s unlikely a business has transformed overnight from a weed shop to selling sodas and chips only.”

Yet, while some illegal pot places try to skirt the crackdown — Empire Cannabis, at Broadway and Howard Street, reportedly voluntarily shut down during the first enforcement wave, so as to avoid fines — some may be throwing in the towel.

Marte, for one, said there is clear proof the heightened enforcement is working — his bottom line. A number of illegal shops near him recently were hit by law enforcement.

“It’s really making a difference,” he said. “With the five shops they closed down we doubled revenue in a month.”

Unlicensed pot shops in Greenwich Village have not escaped the new pot dragnet. Captain Jason Zeikel, the commanding officer of the 6th Precinct, said he is optimistic this year will see a lot more closures of the unsanctioned stores.

“We look forward to padlocking more illegal smoke shops in the near future,” he said.

Glad for new efforts

The Travel Agency, one of the state’s licensed dispensaries, with three locations, including near Union Square, at 13th Street and Broadway, appreciates government’s new get-tough approach.

“Of course we are not happy with the amount of illegal stores selling cannabis products in New York,” said Arana Hankin-Biggers, The Travel Agency’s co-founder and president, speaking before the launch of Operation Padlock to Protect. “These illicit shops sell untested products that are not safe to consume. They sell frequently to minors, and are attracting crime to our neighborhoods while the state receives none of the tax revenue needed to improve the quality of life for New Yorkers.

“Although initiatives to shut them down are taking longer than we’d like, we applaud Governor Hochul’s newest proposal to expand the authority of government agencies to ramp up enforcement efforts, and are hopeful that her efforts will begin to pay off soon.”

Joanne Wilson, the owner of Gotham cannabis shop on E. Third Street, in an interview prior to the new push against the illegal stores, decried all the unlicensed places being allowed to operate.

“Business could be better,” she shrugged. “Unfortunately, there’s thousands of illegal stores around that are taking business. I don’t know if people even know the difference.

“There’s a lot of threats of enforcement but [after a raid] the stores are open the next day.

“And the illegal stores are not paying taxes.

“The $10,000 fine is a joke,” she scoffed. “This isn’t 1960. You want to stop something? Put a big f—ing number behind it. It should be half a million. Some of these stores could make up to $100,000 a day.”

Plus, Wilson noted, the illegal places are buying highly desirable — but cheaper — California flower versus the New York-grown weed legal stores are required to sell. (One insider predicted that eventually O.C.M. will pivot to allowing local dispensaries to offer the California and Oregon weed that consumers crave.)

Yet, the new enforcement notably includes the ability to seal the scofflaw stores longer — for up to one year. The owners can still fight the closures in OATH court (the city’s administrative law court) — yet, meanwhile, must remain closed.

Illegal stores fight back

However, an attorney recently filed a lawsuit on 27 of the unlicensed stores’ behalf charging that the new enforcement “lacks due process.” Basically, under the current procedure, there is a “roster” that illegal stores get put on based on “observation”; once a shop lands on this list, per the rules, law-enforcement officers can enter it without a warrant, seize merchandise and seal the premises. In response to the lawsuit, the Adams administration has countered that, in this case, the need for a warrant only applies to state agencies.

Cannabis attorney Jeffrey Hoffman represents two of The Travel Agency’s shops, as well as a number of other legal dispensaries. He said the current crackdown could have started in earnest two years ago, if only Albany had O.K.’d enabling legislation — but that, after the state Senate approved the changes, Speaker Carl Heastie declined to bring the matter up for a vote in the Assembly.

“I put the most blame on the Legislature. This is their law,” he said of the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act, or MRTA, which was approved in March 2021. “We were telling them they had a problem in 2022.”

Hoffman feels the foot-dragging following MRTA’s passage was because lawmakers didn’t want to be punitive.

“What was the worst city on anti-cannabis enforcement?” he asked, rhetorically. “New York City. What exactly do you not want to see? Black and brown people being perp-walked.”

Sasha Nutgent, director of retail cannabis at Housing Works Cannabis Co. in Noho, another legal dispensary, also told The Village Sun that it was common knowledge that the authorities had been consciously trying not to come down too hard on the illegal operators.

The current enforcement could work, Hoffman said, but only if there is strong oversight and a willingness to “keep going back” and repeatedly hitting illegal shops that defiantly reopen after being padlocked.

‘Take one building…’

In the attorney’s view, there is a much simpler, more effective way to get landlords to stop renting to the illegal shops.

“You take one building from a landlord,” he said, “and the rest of the landlords will solve the problem for you.”

Otherwise, he said, many of the unlicensed marijuana shops will do exactly what the Lower East source says they are already doing — pretending they are just delis and bodegas selling Fritos and Funyuns, meanwhile vending pre-rolls, gummies, vapes and maybe magic mushrooms, too, from under the counter.

Or, as Hoffman bluntly put it, “The cat and mouse game is on.”

Mar Fitzgerald, the chairperson of the Community Board 2 Cannabis Licensing Committee, said signs of the new crackdown were plainly evident when it started two months ago. She said that one day in early May, after dropping her daughter off at school in Midtown, she walked back toward Greenwich Village down Seventh Avenue and noticed all the illegal pot shops were closed along the avenue from 48th Street to 27th Street.

“They had swept every dispensary,” she said. “There were posters on every store for a 20-block stretch. They had padlocked everything. Weed World had posters plastered on every inch of window space at 36th Street and Seventh Avenue — and they had different dates, which means they went back [to do enforcement] several times.”

However, Fitzgerald said, she has since seen a few of those same stores reopen.

Change ownership — reopen

One store in the E. 30s that had been shut down for several weeks recently suddenly was back in operation. The hookahs and chips and chocolate bars that had been on the shelves before were still there. But the brightly lit, clear lucite display cases — ringed with illuminated green marijuana leaves — that were formerly stocked with pre-rolled joints, edibles and vapes were glaringly totally empty.

Asked if they were selling any pre-rolls, a young guy at the counter, pausing from speaking in Arabic to a co-worker, said, sure: The house ones were $12 and it went up from there, including Zkittlezz (pronounced “Skittles”), a brand of fruit-flavored joints. Asked to see one, he moved a few steps away, reached behind the counter somewhere and produced it within a few seconds.

Asked about the place having reopened, he shrugged, “Yeah, it takes a month.” All you need, he explained, is to form a “new organization” for the store’s ownership.

But the illegal stores reopen much faster on the Lower East Side.

“Maybe somewhere else it’s a month,” the source said. “We got a little over a week.”

Pointing to how tricky it can be to vet the applicants, Fitzgerald recalled the case of one man who came before her committee seeking the blessing of C.B. 2 to open a legal cannabis store in Greenwich Village. However, it turned out his brother was already operating a pot shop in the Village — an illegal one. When Fitzgerald called him out on it at the meeting, the man hung his head in embarrassment. The application was nixed.

In addition, advocates say legal challenges against the current enforcement efforts could cause cannabis regulations to be rewritten yet again (the rules are reportedly constantly being tweaked), likely to be followed by yet another round of lawsuits, leading to more years of limbo with the gray-market stores.

As for the notoriously slow and muddled rollout of the state’s cannabis program and opening of the legal stores, the glitches, delays and lawsuits have been well documented. In another twist, after four years, owners of CAURD (Conditional Adult-Use Retail Dispensary) licenses, the kind that Marte has, can sell them — and the new owners don’t have to have a criminal justice-involved background, diluting the thrust of the program’s intent.

Nevertheless, Fitzgerald, for one, remains confident the cannabis landscape is trending in the right direction

“I want to move into the future,” she said, “with hope.”

About 2 months ago was going into a Dunkin. The owner caught two 11-year-olds from Baruch Middle School with CBD gummies, he took it away from the kids. They ran like crazy out of the store. He said, They are like 10 or 11 years old, who the heck sells this stuff to kids?