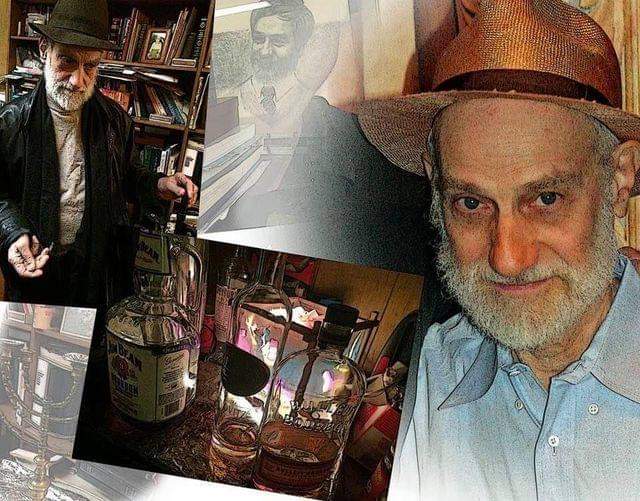

BY THE VILLAGE SUN | Updated Fri., Oct. 3, 1:12 p.m.: Herman Lowenhar, the longtime president of the Charles Street Synagogue, also known as Congregation Darech Amuno and the Greenwich Village Synagogue, died on Tues., Sept. 29. He was 86.

The cause of death wasn’t immediately known. According to a friend, Ben Kohanim, Lowenhar’s brother reportedly found him in his apartment.

The funeral was graveside at Sharon Gardens, in Valhalla, Westchester, on Thursday afternoon, according to Kohanim.

In his younger days, Lowenhar was part of the Village’s bohemian scene. He got involved with the synagogue in his 40s, started fixing things there if they needed fixing, and never left. A music lover, under him, the synagogue famously became known for hosting rousing bluegrass and jazz concerts.

More recently, the concerts had been moved to the synagogue’s basement, so as to avoid complaints by neighbors, and then had stopped for a while. But Lowenhar had started reviving the tradition last fall.

In a eulogy, his daughter, Amy Loewenhaar-Blauweiss, a psychotherapist and faculty member at Bard College, noted that her father “had many lives.”

“There were many incarnations of my dad,” she said. “At a very, very early age…he essentially got himself adopted into the childless households of two of the major artists at the Educational Alliance Art School. And so it was that a part of his development was about having grown up with members of the Algonquin Round Table — people like Dorothy Parker and Franklin Pierce Adams — in the ferment of the West Village in the mid- and late 1940s.

“In 1948, he worked for voter integration in Virginia, alongside Henry Wallace, while Wallace was campaigning [for president]. One of his proudest moments was when Wallace and he stood side by side on stage and Wallace took his hand and held it up in solidarity.

“In his early 20s,” his daughter continued, “he lived in a small community in Upstate New York, where he experienced a kind of picture-postcard Americana, and he found a way to both become the image of his surroundings, as well as to make them his own by integrating himself into the social fabric of the community and helping anyone in need. The friendships made during that time were foundational in his understanding of himself as first-generation American.

“Back in the city, in the 1950s, he was at the epicenter of Beatnik culture,” Loewenhaar-Blauweiss recalled. “When he met my mother at a party at my maternal grandmother’s apartment in the West Village, he was actually on his way to Crete. He had become a huge fan of the writer Nikos Kazantzakis and he was planning to make a pilgrimage. He had become involved in all things Greek. He was studying Greek with an elderly priest and, at one point, at a taverna in Astoria, he pointed to a cop sitting on a white horse and said what was roughly equivalent to, ‘Behold yonder blanched steed!’ In his unbridled enthusiasm for learning, he had not realized that the priest was teaching him Church Greek.

“How many kids read Henry Miller under their father’s watchful eye at 11 or 12? He was the most progressive educator imaginable, while still remaining absolutely loyal to a vast body of classical literature, history and philosophy. He was reading “War & Peace” for the third time during quarantine.

“He also had a brilliant scientific and mathematical mind,” his daughter recalled. “In 1968, while working as an investigative journalist for Space Aeronautics, he determined, based on measurements he was able to take while undercover, that our antiballistic missile system left us vulnerable for a full second. He was called to testify before Congress. It was no surprise that he turned out to be right, and that he also had no job waiting for him upon his return to New York.

“He spent the next several years working to support us by installing elevators in factories in Soho after hours and delivering refrigerators to walk up apartments. Needless to say he had my baby brother and I in tow so that my mother could work at home on the Russian encyclopedia she proofread for two years. I still went to private school and I still had piano lessons.

“Desperate to have children, he changed course and had a family and I was lucky enough to grow up in Greenwich Village in the ’60s and the ’70s in my father’s eccentric social world, peopled with characters of every imaginable stripe, state, age and persuasion.

“In his 40s, my father found the synagogue on Charles Street that became the focus of his life for the rest of his life. He must have passed this shul a million times without ever stopping in. … But on this particular day, he did stop in and then started attending services, and within very short order, there was a problem at the shul and it needed fixing or solving or rescuing, and my father decided to fix it and solve it and rescue it. And you know the rest of the story.

“Yet, even in my father’s orthodoxy, there was a heterodoxy that expanded to include the legendary musical life of that shul, and the thousands and thousands of people over the years of — again — every imaginable stripe, who became a part of my father’s concentric social universe.

“The consistent line that ran through the many historical selves he inhabited was his drive, his caring for others, his restlessness and his fierce intellect.”

The full eulogy is posted on the Charles Street Synagogue’s Facebook page.

The Andy Statman Trio played a decades-long running series of bluegrass concerts at the synagogue. In a post on Facebook, they wrote, “It is with the deepest sadness that we report the loss of our beloved friend Herman Lowenhar… . He was brilliant, loving and served as the genial and erudite host of our twenty-year concert series at the Charles Street Synagogue. Anyone who has joined us there knows that Herman was at least as important to the experience of our concerts as our music, and we shall miss him terribly.”

A fan of the Andy Statman Trio, Aaron Kleinbaum, posted on Facebook, calling Lowenhar a tzadik, or “righteous one” in Yiddish.

“Herman embodied all traits that a true Tzadik should have,” he wrote. “His warmth at welcoming guests to Charles Street is a memory many fans of Andy’s probably have. Though I was probably in his presence five to 10 times in my life, I will never forget this man.”

Also on Facebook, Uri Schneider wrote, “Herman was truly one of the most magnificent people on the planet. A constant spirit of generosity, giving and service to others. Yes, Dena and I frequented the Andy Statman Trio, and the highlight was MORE THAN THE MUSICAL MAGNIFICENCE… It was the incredible ambiance cultivated by Herman as he welcomed high-brow bluegrass and jazz enthusiasts from around the world, along with the Hasidic guests from Williamsburg, and the ‘rest of us’…with the same authenticity, humility humor and…l’chaim!

“He would serve bourbon and slivovitz in the basement of the Charles Street Synagogue to the aforementioned crowd,” Schneider recalled. “It is something you cannot imagine if you never had the privilege to be there. Truly, otherworldly.

“I am sad to learn that his spark has left the world, but his warmth will stay with me forever.”

A 2012 article in Mandolin Cafe, by Scott Tichenor, captures some of the spirit of Herman Lowenhar and the concerts at the Charles St. Synagogue.

Clarification: The original version of this article listed a cause of death for Herman Lowenhar that was not confirmed. That sentence has been removed from the article.

An obituary for a controversial person should be warts and all. My wife and I were among the substantial portion of the congregation at Derech Amuno who left the shul after Herman engineered the hiring of a part-time rabbi by exploiting a technicality in the synagogue’s bylaws. The hire needed to be voted upon by the congregation, and Lowenhar arranged to be given the proxy votes of people who had contributed to the shul but didn’t actually worship there. As I recall, roughly half of the congregation left because of that. (A similar effort was made at the Community Synagogue on E. 6th Street by the Australian Lubavitcher Simon Jacobson but failed. It took a six-figure effort to thwart the move in court.) After my wife and I left Derech Amuno, Herman insisted on continuing to send us the annual letter he sent to congregants. Those letters were used to disseminate Herman’s personal views on political matters, including his insistence that President Obama was a Muslim.