BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Forget (for a moment, at least) abortion, gun control, expanding the Supreme Court and even monkeypox. One of the hottest issues in the 10th Congressional District primary election is East River Park.

On Tuesday, former Trump impeachment attorney Dan Goldman visited Corlears Hook on the Lower East Side to hear from park activists and see what former City Councilmember Kathryn Freed termed “the devastation.” The nearly 50-acre park’s southern half has been completely bulldozed for the East Side Coastal Resiliency megaproject. The park is being clear-cut, in a two-phase job, in order to elevate it 8 feet to create a flood barrier.

Not to be outdone, on Friday afternoon, Congressmember Mondaire Jones will also visit the same section of East River Park and meet with activists.

In addition, on Thursday afternoon, five minutes into an interview with Paul DeRienzo, the director of WBAI News, Jones accused Councilmember Carlina Rivera of “breaking her promise” to allow community input on the E.S.C.R. plan.

“Have you dipped your feet into any of these issues [surrounding East River Park],” DeRienzo asked Jones.

“Of course I have,” the representative responded. “You know, when I speak to folks in the Lower East Side, they are furious at their city councilmember, Carlina Rivera, for breaking her promise to them that there would be community input when it comes to the Lower East Side resiliency project. That’s why they’ve been protesting outside of every forum and debate we’ve been having for the past month and a half. …

“There are real differences between the candidates in this primary,” Jones said.

Asked by DeRienzo, if elected, whether he would “use his power to slow down or possibly change the [E.S.C.R.] project or scope of it,” Jones did not answer the question directly, but said, “I think we’ve gotta have community input. We’ve gotta have community input. There are a lot of concerns about the way the project went down, broken promises. Obviously, I’m a staunch supporter of being climate resilient — that is going to change lives. But we can do it in a way that is humane and preserves the social life of people in the Lower East Side — and that includes, by the way, a lot of low-income Black and brown people who deserve to have a park in a way that other communities throughout the city have.”

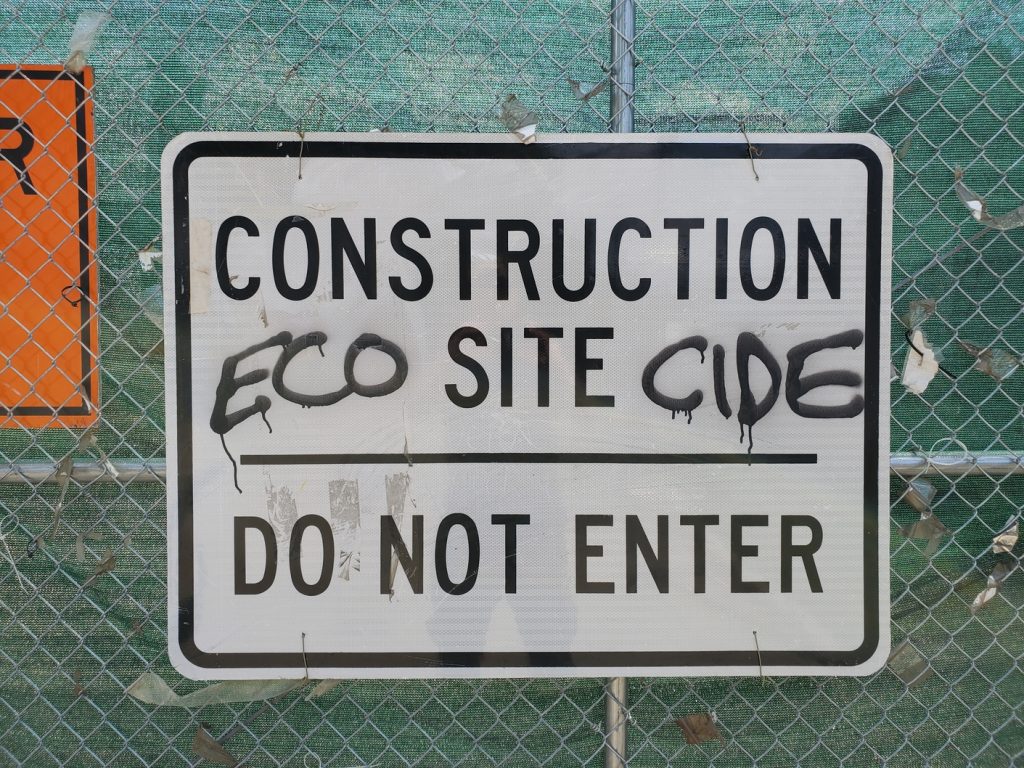

During Goldman’s visit to the park on Tuesday, he and the activists met near the now-chopped-down, former grove of cherry trees in Corlears Hook Park, then walked over the temporary bridge toward the NYC Ferry dock to survey the scene.

As they stood baking under the blazing sun amid the now-barren, treeless landscape, Goldman, who lives in Tribeca, mainly listened to what the park activists had to say — and they had a lot to say. The E.S.C.R. opponents spoke passionately, peppering him about the lack of transparency and accountability that they charge has plagued the project. They also stressed to him that they felt there were better alternative plans that wouldn’t have destroyed the entire park and all of its trees.

After reading in The Village Sun that Goldman would visit the park, the Frontline Communities Coalition — which includes tenant leaders of New York City Housing Authority complexes bordering the park — in a tweet asked if Goldman would also stop by the nearby NYCHA houses and hear from residents about the “devastation” they suffered from Hurricane Sandy’s flooding. So, The Village Sun asked him.

“I did,” Goldman answered. “I went around the Jacob Riis Houses with the tenant association.”

After the tour, The Village Sun had some more questions for Goldman — basically, what he thought after seeing the deforested former park landscape and whether he felt the resiliency project could and should have been done differently. But he had to rush off to his next campaign stop.

The newspaper e-mailed the questions for Goldman to Simone Kanter, the candidate’s communications director, who responded that, like Jones, Goldman thinks community input is essential for large-scale projects like this.

“Dan feels strongly that transparency should always be a priority and that it’s incredibly important to hear the concerns of the affected community on any given issue,” Kanter said. “When in Congress he looks forward to taking into account a wide range of perspectives on critical issues and working in partnership with the community to solve the challenges we face.”

Allie Ryan, the former City Council candidate, joined the park tour with her two young daughters, Virginia and Ruby Lee, in tow. The East Village family used to regularly use the waterfront green oasis. Ryan gazed from the bridge toward the northeast where a yellowing field of grass sat cordoned off behind a chain-link fence. Several people were squeezed into a corner of the field, having found a tiny bit of shade there.

“That’s supposed to be a passive open field,” Ryan remarked, “but it looks like the grass is dying.”

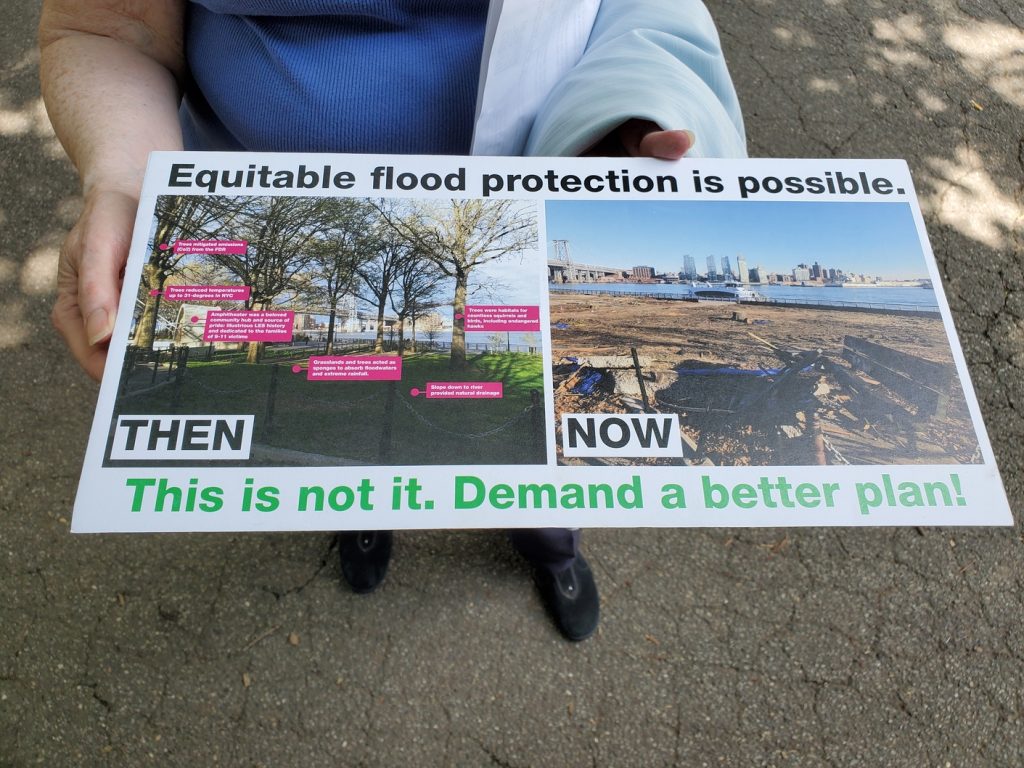

Freed showed Goldman large color prints of photos snapped by Pat Arnow, a leader of the group East River Park ACTION, depicting once-bucolic park scenes, like the shade-dappled wooden seating of the historic amphitheater. Today a large pile of rubble sits where the since-demolished performance venue once stood.

Freed said she supported a previous version of the resiliency plan that would have erected a berm along the F.D.R. Drive and would have only needed to destroy around 200 or 300 trees. Although E.S.C.R. supporters point to a comparison chart that shows the “berm plan” would have felled nearly 800 trees — or only 200 or so less than the nearly 1,000 under E.S.C.R. — Freed avers that, in her research, she is sure she saw an early version of the plan with the lower tree-kill count.

Freed, like other E.S.C.R. opponents, feels the park didn’t need to be raised but should have been allowed to function as “a sponge” in the event of storm surges, absorbing the floodwaters. While she conceded that would also have eventually transformed parts of East River Park into “marshland,” she contended that’s O.K. since it’s a natural flood barrier.

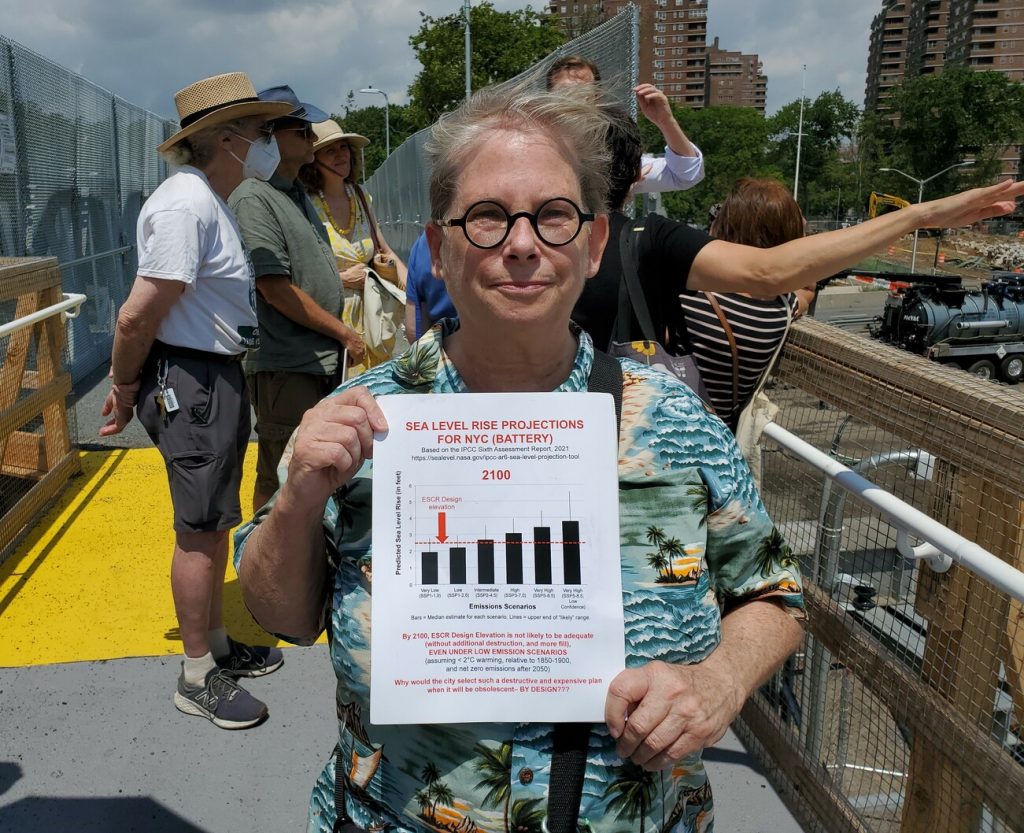

Meanwhile, Amy Berkov, a longtime tropical ecologist, said she backed an even earlier resiliency design that would have included simply erecting a new wall along the F.D.R. and only killing around 200 trees. Instead of fixating on the number of trees, though, Berkov said the key should have been to try to keep as many of the older, larger trees — and thus as much of the existing tree canopy — as possible, instead of wiping away the entire existing park. Plus, she scoffed that, since sea levels are predicted to keep rising, the E.S.C.R. protections will soon be ineffective anyway.

“My feeling is all of these plans are going to be obsolete in two decades,” she noted. “So why wouldn’t you take the least expensive and least destructive plan? And the least destructive was a wall.”

Ideally, the E.S.C.R. opponents generally supported the idea of “decking over” at least one lane of the F.D.R. to expand the park westward and help cut down on carbon emissions in the green space. Although the community bought into this design, the city never got on board with the idea of covering part of the highway.

John Plenge, a Parsons teacher and musician living in the East Village, noted that Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine just that morning had called for converting a lane of the West Side Highway into an expansion of the overcrowded Hudson River bikeway. Plenge said decking over part of the F.D.R. is basically the same kind of bold thinking as Levine’s proposal.

“If they can talk about that on the West Side, why not here?” he asked.

Again, for the most part, Goldman was mainly listening to the activists air their concerns. Freed said that, at one point, he asked if the opponents “want resiliency.”

“He didn’t say anything specific to me,” Ryan said. “My impression was he was listening, too — trying to get a better understanding of the difference between the current E.S.C.R. and the community-led E.S.C.R.”

Meanwhile, longtime Democratic political strategist Hank Sheinkopf, downplayed the importance of the contentious East River Park issue in the District 10 race in an election season full of pressing national issues, like abortion and the fight to save American democracy itself.

“In that district,” he shrugged, “they’re going to be talking about larger social issues.”

Growing up in Gramercy, it was through this park where I met my LES neighbors and saw a different side of my own backyard. The park served as an anchor of integration in an increasingly elitist city. Thanks, Carlina, for voting for the final nail in the coffin.

I agree that a barrier wall would have worked well and kept the lovely and necessary park. My son, a Cooper Union student, lives in the East Village, whom we visit often. Also, as a reference point, The Southwest Corridor Linear Park in Boston, a beautiful park adorned with community gardens, was created by decking over the Orange Line train tracks.

I don’t know where Hank Sheinkopf lives… Coastal resiliency is my #1 issue for this race. NY10 has a tremendous amount of coastline: Lower Manhattan, Governors Island and Brooklyn. (Yes, Governors Island is located in NY10.)

Hank Sheinkopf is the same “pundit” who predicted in this paper in June that Bill de Blasio would win this election. We all know that de Blasio has since dropped out in disgrace, since he was polling at the bottom.

The folks I talk to do not have “social issues” primarily on their minds in this election. The candidates generally agree on things like abortion, guns and human rights.

This election is more about political integrity, experience in the neighborhood and a candidate’s past record of accomplishments. Mr. Sheinkopf should indeed spend some time down here before making erroneous statements.

Just to clarify: My preference for the least expensive, least destructive floodwall was a preference among the options included in the ESCR Environmental Impact Statement. Decking over the FDR was not included… but that would increase open space, lift the athletic fields out of harm’s way, and — in terms of a flood barrier — stand the test of time.