BY ISAAC SULTAN | The Supreme Court’s 6-to-3 decision rang out from Washington, D.C., on June 15: The justices’ landmark ruling will protect the rights of L.G.B.T.Q. people from workplace discrimination across the United States.

Though the moment emanated from the nation’s capital, it was a victory for the gay rights movement that is deeply rooted in the history of activism, protest and leadership of Greenwich Village.

“An employer who fires an individual merely for being gay or transgender defies the law,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for the majority opinion.

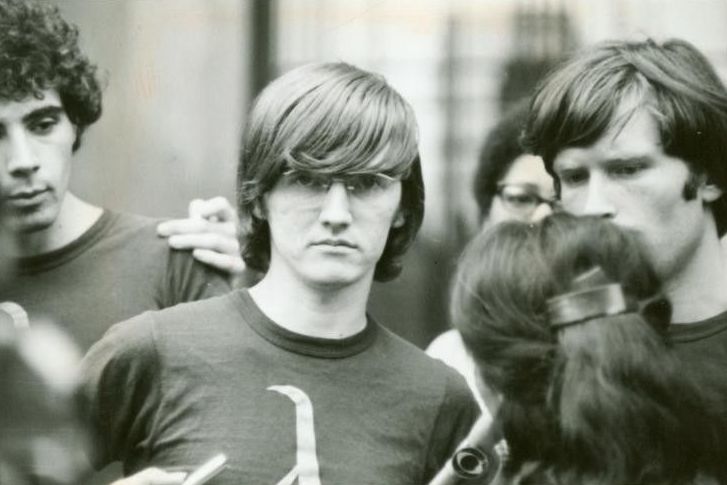

Gorsuch’s words stand on the foundation laid by local New York City trailblazers like Jim Owles, who have advocated for equal rights since the 1970s.

In 1969, Greenwich Villager Owles founded the Gay Activists Alliance of New York, the largest militant gay rights organization in the United States. Four years later, he became the nation’s first openly gay man to run for public office.

“Gays must redirect anger that has been largely inward, outward — where it belongs,” Owles said. “That doesn’t mean smashing windows. It means confronting people who do have the power and saying, ‘Look here, ours are not ridiculous or frivolous demands — they’re something every American should have!’”

Owles and fellow gay activists shared a building on Spring St.

He was one of the architects of the first gay rights bills to be introduced in New York City — and the country, in general. Furthermore, the bill was introduced by two Village congressmembers, Ed Koch and Bella Abzug.

It was a document that would become an important touchstone for federal legislation in the years to come to fight discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. After dedicating his life to improving gay rights, Owles died from AIDS at age 44 in 1993.

Another Village resident, Bruce Voeller, co-founded the National Gay Task Force in 1973, the first national gay rights organization in the U.S. As the organization’s first director, he was a regular witness before Congress, proudly discussing his homosexuality and boldly advocating for the gay rights movement on a national scale. Voeller’s leadership was influential in introducing anti-discrimination legislation to Congress. He was a leading voice and researcher in the fight against AIDS before passing away from the disease at the age of 59.

In an op-ed, Andrew Berman, the executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, remarked that, “As has so often been the case, ideas put forward and championed in the Village eventually filter their way into the mainstream, in this case nearly 50 years later. It’s always gratifying and amazing to see how much the Village leads the country and the world in terms of thought, ideas and action, especially in the arena of civil rights and social justice.”

Indeed, the legal protections written into the law of the land earlier this month are ones that past activists like Owles, Voeller and countless other men and women across the nation would only have imagined. As Berman noted, it is perhaps no surprise, though, that such meaningful change was instigated from the crooked streets of New York’s one and only Greenwich Village.

Jim Owles is truly one of the movement’s heroes. He would most certainly be proud of the steps forward the LGBT movement has achieved since his death in the summer of 1993.

“We do not ask for any respectability or sympathy from straight people. Others’ opinions are of no interest to us except to the extent that these private bigotries are allowed to become public policy.” — Jim Owles (1946 – 1993)

Much of the work done to make these historic gains in civil rights took place in buildings which still stand in our neighborhood, but without Landmarks protections and could be lost at any time. Help us to get them landmarked: Send a letter at http://www.gvshp.org/mayor.