BY MICHELE HERMAN | Saturday, March 28: My mother’s 1950s Singer is the comforting color of chocolate milk with an extra squirt of Bosco stirred in.

I hoist it onto the dining table at the end of week two of sheltering in place. I bring out my gear, so much gear for such a small project: ironing board, iron, scissors, shears, pins, measuring tape, seam ripper (praying: please let me not need to use it), thread, bobbin, fabric, cutting mat and blade.

I also haul out all the bras in my drawer that are in the limbo between wearable-in-a-pinch and tossable, and every length of washable ribbon I can scrounge around the apartment.

I have found a new way to be of use: I am going to make some face masks.

I’ve looked at various patterns on the Web and have chosen the most professional-looking one: rectangular masks with proper seams and pleats and a little pocket at the top into which the wearer can stuff extra layers of insulation. This pattern requires a little sewing know-how, which I have.

No one has yet recommended that we all wear masks and no one really knows how effective they are, but the Times has run a feature about people sewing their own to free up the real ones for those on the front lines, and I’m a New Yorker: If the Times sanctions it, it must be real.

Aside from a car, a sewing machine is the only piece of heavy machinery I know how to operate, which is one more than many people. I feel extremely grateful that my seamstress mother taught me to use it and kept it well-lubricated and dust free for half a century.

It’s a good inheritance — this solid body with its complicated steel organs, its slight smell of oil, its lightly humming motor, its simple drop-in bobbin, its many zigzag options, its quick acceleration when I put the pedal to the floor, the chorus of healthy sounds it makes when sinking its teeth into whatever I feed it.

It takes me a while to get the hang of the task at hand, which seems to have way too many steps. It takes me most of the afternoon to make four masks.

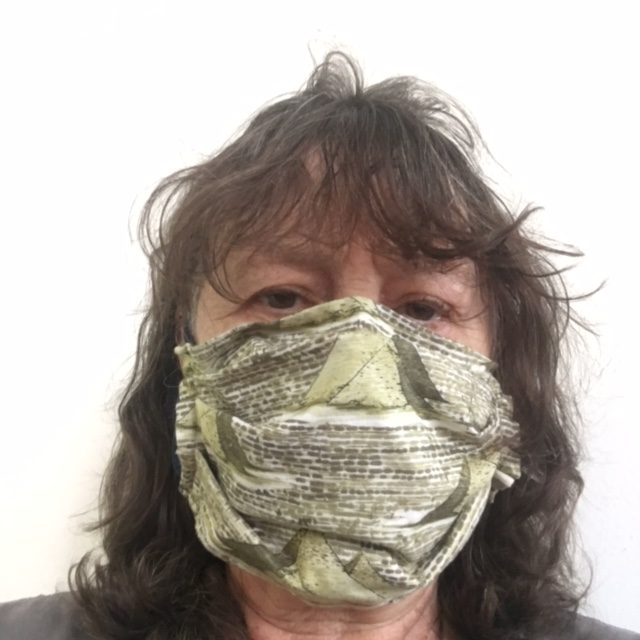

I use a piece of fabric given to me by a former down-the-hall neighbor, one of the original tenants of our converted warehouse. It’s cotton broadcloth printed with a pattern of pyramids in pale greens on a white background. She thought our boys might find a use for it, maybe for a school project, but they never did.

She could be a very difficult neighbor, but she was also generous, and always kind to our sons. I’m using the fabric as a tribute to her kindness and as a little in-joke, since some of the masks may help protect the faces of staffers she yelled at over the years.

Saturday’s masks: the two prettiest are the ones with the like-new elastic bra straps (adjustable!) sewn into the side seams as ear loops. The two others have ties at each of the four corners: One has bright green seam binding that I’ve cut in half down the middle and zigzagged at the edges to create enough lengths; the other has some polyester hem tape I found amid my sewing things, so old the cellophane covering the package crumbled when I removed it.

While digging in corners of our clothes closet for usable fabric, I come upon five brand-new white men’s T-shirts. My husband reminds me that he needed only one for a costume for his acting class, but it was cheaper to buy the six-pack at K-Mart.

Sunday, March 29: I take a deep breath and cut into one of the virgin Hanes T-shirts, all cotton, made in our hemisphere, in El Salvador. The cotton is thick and soft.

How had I never noticed the miracle of a white T-shirt — its completely seamless body, the ring of ribbing at its neckline falling perfectly into place, its even double rows of stitching at the shoulders and sleeves?

I will never have the skill of my mother, nor of whatever combination of sweatshop workers and robots made these shirts. Unfortunately, once I sew seams and insert ties and then pin three pleats into place, the sides of the masks are so thick, even the Singer struggles to scale the lumps. I have to keep lifting the presser foot and coaxing it along.

But everything is relative. I am in my own home with no boss scrutinizing my meager output, and I can get up and take a break whenever I want. As I keep telling friends who ask how I am: So far I’m healthy, I’m dry, I’m comfortable, I have food to eat and work to do and Netflix for the evenings; I’m fine.

Sunday evening, when I take the eight masks out of the dryer after laundering them, the polyester hem tape has wrapped itself around all the other masks tight as a phylactery.

Wearing rubber gloves, I spend half an hour disentangling them. I pack the clean masks in the fancy Ziploc sandwich bags we acquired at some point and that I never use because they seemed so fancy; the proverbial rainy day is here, a deadly storm with no end in sight.

Monday morning I give two masks to my super, who’s running low on disposable ones and is touched by the gesture. A friend who works for the V.A. posted something on Facebook about a need for P.P.E., so I call her up. She tells me the Army can’t take anything that’s not government sanctioned. But she mentions two friends, women I also know and like, who both happen to be diabetic and are afraid to go out.

I bike up from the Village to the Upper West Side to the bare-bones postwar high-rise on a desolate block in the 60s where one lives, and to the beautiful small apartment building just off Riverside Drive in the 90s where the other lives. Everything is relative. I get back effusive thank-yous.

Then I put a note up on NextDoor.com and get some takers. I spend the afternoon delivering masks to buildings in the Village and Chelsea, making different arrangements with each person for dropping them off without touching anyone. Here’s a note I get back from one of them, a self-described senior citizen:

You are so kind, I really appreciate it.

If there is anything I can do in return, please let me know.

I am a clinical psychologist, so if you need any emotional support

during this surreal time, I am more than happy to help.

Friday, April 3: My inbox has been filled all week with requests for masks. More than one stranger has told me I should go into business and get paid for my efforts. Someone offers to pay me a chunk of money on Venmo for my time and materials.

But I’ve been busy with my own work and my two ongoing online writing classes. I have also taken over a colleague’s live class, which is now a video class on a new app I have to learn, having already kind of learned Zoom a couple of weeks ago for my piano lessons.

Today Mayor de Blasio is recommending that all New Yorkers wear a mask whenever they go out, the main reasoning being that some of us may be asymptomatic carriers of the virus. Now I, the seamstress’s daughter, am the maskless one.

I hoist the Singer onto the table again and line up the gear. Last time I spent far too much time going back and forth between the sewing machine and the ironing board, my staging area. I’m determined to streamline the process.

This time I use cut-up pieces of old tights for ear loops, and for the ones with ties I’ve figured out how to feed eight lengths into the machine one immediately after another for zigzagging, so I don’t waste thread and time cutting it.

I complete 10 in one afternoon. I’m getting a little better at the pleats. “Pleats” — a word from my distant past. I used to tell my sons that knowledge is never wasted and that you never know when it will come in handy. Case in point.

Saturday, April 4: I’m about to go on NextDoor.com to gather people’s addresses, and then I’ll get on my bike to make deliveries, wearing Hanes cotton knit against my nose and mouth.

What do we learn about humanity in a pandemic? You can find any lesson you want: People are greedy, selfish, ignorant, cavalier.

I prefer a different lesson: People are kind and grateful when you make the smallest gesture.

Thank you, Michele, for your words, your masks, and your generous spirit! I’m, of course, reminded of your poem about your mother;s sewing box. She sewed and spoke in prose….

Thanks, Michele. You are the best! I thank your mother too. My mother was also a good seamstress. I never got the hang of it.