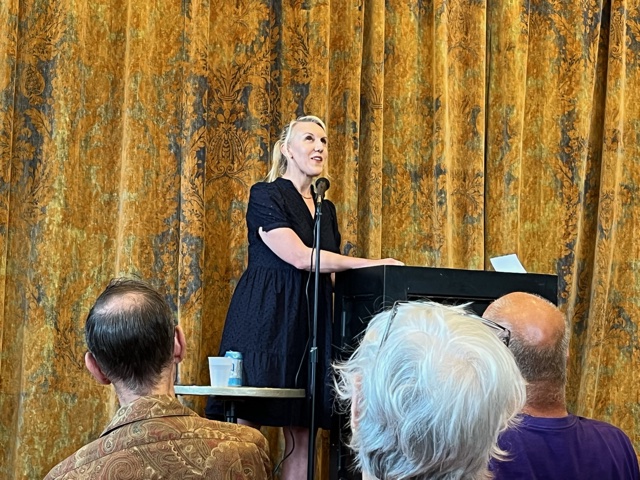

BY CASEY EPSTEIN-GROSS | On July 17, the writer Ada Calhoun returned to the newly reopened Jefferson Market Library — a place where she’d spent countless hours as a little girl — to read from her newest book, “Also A Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me,” which was recently published to rave reviews.

It was a homecoming of sorts. Calhoun, who was born and raised in the East Village, began the talk by recalling her fond memories of the library itself, remembering how she used to take its summer reading program very seriously. She was a voracious reader, especially when reading competitively, and, as she told the crowd, proudly remembers the time she even won a special library pencil for her efforts. Returning to the same spot 40 years later, not to soak in others’ words but to present her own, felt like a full-circle moment made all the more meaningful by the deeply personal content of the book itself.

“Also A Poet” is an unusual, hybrid book that mixes memoir with literary biography, weaving together the life and times of the beloved New York poet Frank O’Hara (1926-1966) with Calhoun’s own. The book focuses in particular on her fraught relationship with her distant father, the acclaimed New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl, and their shared love for O’Hara — one of the few things that she always felt connected them.

Several years ago, Calhoun stumbled on a box of dusty cassette tapes filled with dozens of hours of interviews with famous writers and artists that her father had conducted in the 1970s when he was contracted to write a biography of O’Hara, one of Schjeldahl’s personal heroes. Upon learning that her father had never completed the biography because he ran into problems with the poet’s estate, Calhoun decided she could succeed where her dad had failed and told him she was going to finish the book herself.

Her father’s response was underwhelming, but she went forward with the project anyway. She was sure that her general ease with people would ingratiate her to Frank O’Hara’s sister, the head of his estate, whose negative interactions with Schjeldahl were one of the primary reasons his progress stalled. As Calhoun explained to the crowd, however, it did not go as smoothly as she had hoped, and the biography she expected to write somehow morphed into a book retelling the experience of writing it, a meditation on confidence, forgiveness, parenthood, moving forward and writing itself.

Calhoun’s previous works include a variety of ghostwritten celebrity biographies, a critically acclaimed history of St. Mark’s Place and the East Village (“St. Marks Is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street”) and a series of essays on marriage and modern relationships. This, however, is by far her most raw and personal book to date.

After her reading, multiple attendees approached her and thanked her for her candor and vulnerability both in the book and in the talk. It’s true — “Also A Poet” is an exercise in honesty, in telling the painful truth, even when it hurts. When it comes to her father, Calhoun pulls no punches, revealing Schjeldahl to be a difficult person and detached father with far more affection for his work than his daughter. For most of her life, Calhoun had struggled to voice these feelings. She confided that she plunged ahead with this brutally candid book because her father was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer while she was in the midst of working on it: He was given what was essentially a death sentence, meaning that she wrote it thinking he wouldn’t be alive to read it.

But, surprising everyone, Schjeldahl beat the odds, leaving Calhoun with a full manuscript and a deep uncertainty about where to go from there. Even so, she decided to show her father the book, figuring it was the only real way forward. It turns out her fear was unwarranted. Her father loved the book, even saying it was one of the best he had ever read, and all of the discomfort it brought him was overshadowed by the strengths of the book as a whole. This, Calhoun said, was more praise and respect than her father had shown her in her entire life, and the sense of closure she felt was immeasurable.

Calhoun recited several of O’Hara’s poems about daily life in New York, read passages from the book and talked about its origins, and responded to a varied set of questions from the lively and engaged audience. As this suggests, much like the book itself, Calhoun’s talk at Jefferson Market Library was a hybrid of sorts: Part of the crowd was clearly there for Frank O’Hara, part for the father-daughter drama, and part perhaps because “Also A Poet” is the next book on the list for the library’s book club.

As Calhoun said, this strange combination of people drawn to the book has been one of the most rewarding aspects of its widespread success: In the process of writing her own story, she has been able to introduce O’Hara’s wonderful work to many who otherwise would never have read him.

Sometimes there are books written because the author needs to write them, and sometimes there are books written because the audience needs to read them. “Also A Poet” is both. Whether you’re looking for an intense chronicle of a difficult relationship that might feel all too real at times, an insight into the process and struggles of writing a biography when faced with an uncooperative literary estate, or an introduction into the work of one of the great poets of New York, Frank O’Hara, “Also A Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me” will have something for everyone.

Fantastic article! Thank you!