BY STEPHEN DiLAURO | At the end of Julian Schnabel’s biopic “Basquiat,” the title character says, “We’re going to Ireland and have a drink in every bar.” A little while later in real life, Basquiat was dead of a heroin overdose at age 27. He never made it to Ireland.

I was recently invited to visit Dublin by someone who was a close friend of the late art world wunderkind. My host, a former New York artist who now enjoys Irish citizenship, is considered something of an expert on Basquiat, having been a consultant on two major museum shows. He asked that I not use his name in this article. He has a very low opinion of the contemporary art market.

“Jean-Michel’s theme was diseased culture, which we talked about on numerous occasions,” my host told me. “Now all those people buying his work for tens of millions of dollars are the people who make the culture diseased. They are the disease, infecting not just the culture but the entire planet.”

But I’m getting ahead of the story.

Dublin, with 92 percent of the Irish population having received their vaccination jabs, was opening up when I arrived. (On Oct. 22, all pandemic restrictions, including masks and social distancing, will be lifted.) One evening, my host invited me to join him and attend an art opening.

The place was thronged and buzzing. Every one of the 30 or so paintings, by a young Dublin artist who goes by the single name of Maser, had sold. Excitement at such success was coupled with the end of lockdown. As often happened during my visit, a stranger struck up a conversation with me. An Irish businessman and art collector, he also prefers to remain anonymous.

When he heard that I write about art and am from New York City, he said, “I have a Basquiat painting in my collection. At least, I think it’s a Basquiat.”

He told me how, in 1989, on a trip to Manhattan, he was partying one night with a friend named Mel. Mel took the young visiting businessman to meet some people in the East Village.

This Dubliner, according to his own account, was no stranger to powdered drugs in those years.

“I was all about wads of cash, cocaine and limousines,” he said. “That could be why people liked to party with me.”

On the 1989 evening in question, he was introduced to some people whose names he does not recall. As the evening progressed, it became clear that the person whose home they were visiting was seriously in need of a heroin fix. Mel asked the Dubliner if their host could borrow some money if he provided an artwork as collateral.

“Mel told me the piece was a Sumo, or Samu, or something like that,” he told me. “I didn’t know what he was talking about. But I didn’t want to see the guy get dope sick, so I gave him a grand and he gave me the piece.”

Basquiat was three years in his grave by this point in time.

Of course, the art collector now knows that the piece was (quite possibly) by Jean-Michel Basquiat and that Samo was the famous graffiti duo of which the late artist was half.

“At the time I didn’t know who either Basquiat or Samo were,” he admitted. “I probably would have given the guy the money without any collateral because I was really stoned and didn’t want to see him get dope sick.”

Mel, he told me, died of an overdose about seven years ago.

I beckoned my host to join the conversation and asked the Dubliner to repeat the story. Soon we had an invite to the man’s home to examine the purported Basquiat. Later that night, in my room in my host’s home, an almost electric excitement staved off sleep. Was I about to discover an unknown Basquiat masterpiece?

Two days later we headed to the Dubliner’s house in Francis Street, the heart of Dublin’s antique district. He lives in a charming multilevel home chockablock with art and antiques. My host said it reminded him more of Paris than Dublin.

In the living room, my attention immediately went to a large (104 cm x 122 cm) baroque painting that looked to me to be old enough to be authentic. The Dubliner said it was “Judith With the Head of Holofernes,” created in 1613 by Cristifano Allori (1577 – 1621), a Florentine mannerist painter. The piece in front of me was a copy from the period, probably made in the Allori studio. It is an impressive piece.

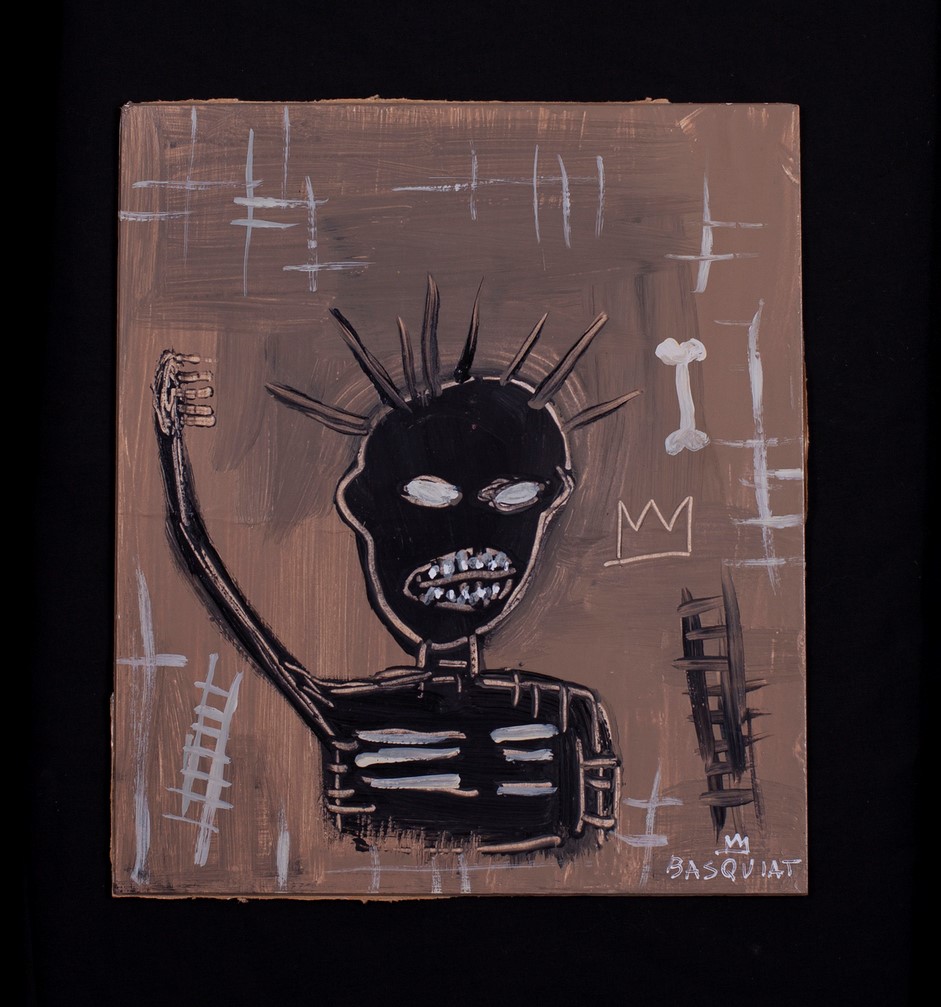

Meanwhile, my host was looking intently at a small (24 cm x 28 cm), framed work hanging on the wall. It had attracted him much the same as the Allori had immediately caught my eye. I was a bit deflated upon realizing that this was the Basquiat we had come to see. It was way too small to be considered a masterpiece. Nonetheless, it was interesting, having a characteristic Basquiat central image, and looked to me to be authentic. But I am not a Basquiat expert.

The Dubliner was very accommodating, allowing us to take it out of the frame and photograph it.

“I’d love to know if it’s real,” he mused. “I’m not going to sell it, but it would be fun to know if it’s genuine.”

My host compulsively documented Basquiat and his techniques and materials photographically back in the day: “The signature looks good, and that’s certainly one of Jean-Michel’s iconic images,” he observed.

So, is it authentic?

“I’d say it’s 80/20 in favor of being real,” my host opined. “I’ve never seen that image rendered so small. On the other hand, it’s on cardboard and he did so many of these things. They were like his calling cards.”

So, what’s it worth?

“Hard to say,” he said. “If it was on canvas it would be worth a lot more. Of course, the market for Jean-Michel’s work is insane these days. If it’s real, it’s certainly worth somewhere in the low six figures. You’d need a second authority like an auction house for it to be considered beyond question.”

“Good to know,” said the Dubliner. “Like I said, it’s not for sale. I just wanted to know for myself.”

“Well, that’s the best I can do,” said my host.

The Dubliner thanked us both for coming. We thanked him for an art world adventure and left.

Later at home, I pumped my host for more: “You said you never saw that image that small. Could it be an early cartoon of the image before he went big with it?”

“Anything is possible,” he answered. “But you would need documentary evidence, like a photo of that exact piece in the studio, to confirm that theory. As it is, there’s no way I’m risking my name and reputation on this. Even if it’s real, it’s not an important piece.”

What did he think of the Dubliner’s story?

“It probably happened just like he said,” he offered. “But that still doesn’t mean it’s authentic. The art world doesn’t work like that and you know it. You have to have provenance.”

I felt a bit like the Oscar Wilde quote regarding those who know the price of everything and the value of nothing. But Wilde was referring to young people and I am anything but. Oh well.

In the end, I got a story out of it. In Dublin, a good tale is almost as good as money. Properly told, it will inevitably lead to someone standing you a pint of Guinness. A story and a pint — sometimes that’s all you need.

DiLauro is a playwright, critic and musician who lives in Greenwich Village.

Be First to Comment