BY ISAAC SULTAN | In an open letter to the Department of Education, the Elizabeth Street Garden’s executive director has offered to let the embattled green space be used for outdoor school classes when the academic year begins next month.

“We understand the complexity of ensuring that children safely receive their education and hope that providing the garden as an outdoor space for learning can serve as an example of resourceful measures during these trying times,” director Joseph Reiver wrote.

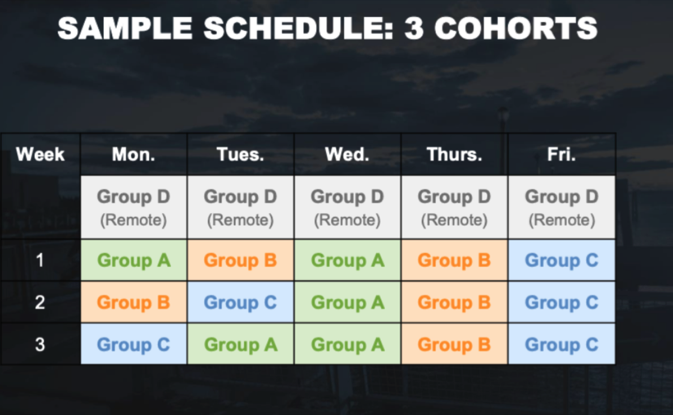

In early July, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the city’s plan to partially reopen its 1,800 public schools in September. The scheme calls for a “blended learning model,” in which students would attend in-person classes two to three days per week and take classes remotely from home for the rest of the week. By staggering attendance, schools aim to reduce their capacity and practice proper social distancing protocols to reduce the spread of COVID.

Outdoor learning could offer schools greater flexibility — and Reiver is not the only New Yorker endorsing it. An online petition organized by a group of New York City public school parents calling for the implementation of outdoor classes has garnered nearly 4,000 signatures so far.

“A combination of street closures adjacent to our public schools and a reimagining of our vast network of public parks will provide much of the needed outdoor space to make an outdoor schooling program achievable and successful for all,” the petition argues.

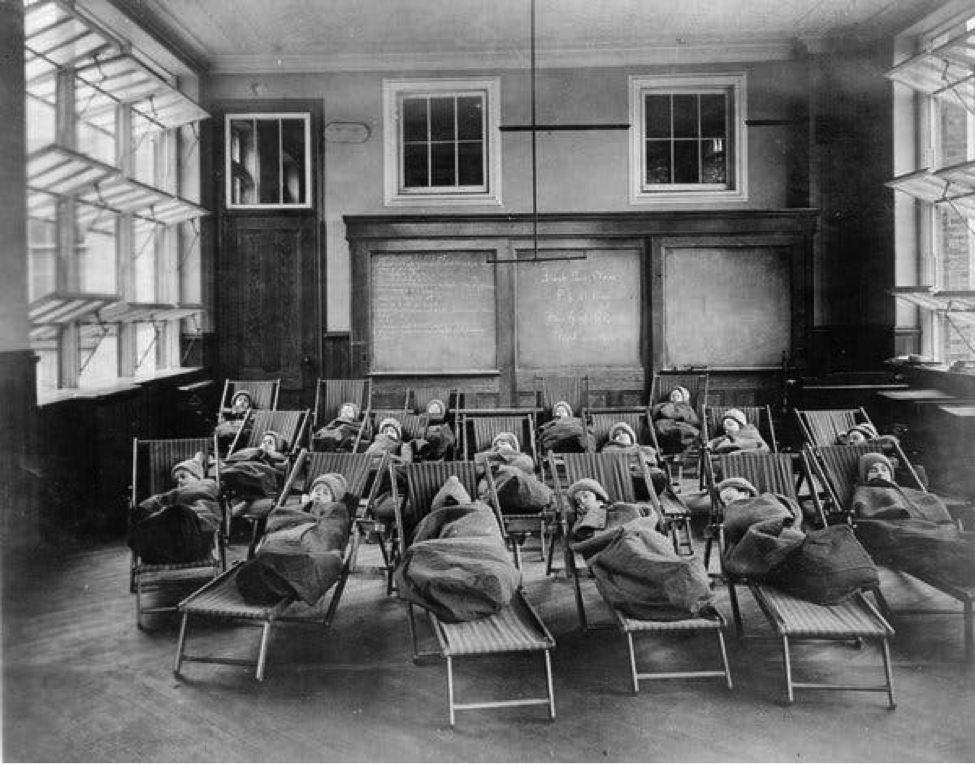

In fact, this kind of creative pandemic solution actually holds direct historical precedents in New York City. During the tuberculosis outbreak of the early 20th century, a number of city schools cracked their windows wide open and also took to rooftops, parks and even ferries to conduct classes, with students and teachers resolutely bundled up in blankets when temperatures dropped.

The archival images of these open-air classrooms from 100 years ago might seem outlandish. But these approaches were successful in slowing the spread of the disease back then, and research indicates similar measures might be successful in combatting the coronavirus of today.

“A Japanese study of 100 cases found that the odds of catching the coronavirus are nearly 20 times higher indoors than outdoors,” reporter Tara Parker-Pope wrote in a recent New York Times article. “Outdoor gatherings lower risk because wind disperses viral droplets, and sunlight can kill some of the virus. Open spaces prevent the virus from building up in concentrated amounts and being inhaled, which can happen indoors when infected people exhale in a confined space for long stretches of time.”

In another historical connection with education and open space, the Elizabeth Street Garden actually sits on the site of the playground of a former public school. Originally named P.S. 106 and later P.S. 21, the school stood on the block until the 1970s.

Reiver said the opportunity to offer outdoor classes in the Little Italy garden demonstrates just another reason why the space is valuable to its community and should be protected. The treasured green oasis remains under threat of demolition for a senior affordable housing project being pushed by Councilmember Margaret Chin and de Blasio. A community lawsuit was filed last year to block the project, buoyed by the rallying cry “Save the Garden.”

“Spaces like the Elizabeth Street Garden are more important than ever now,” Reiver said. “All these elected officials had their own reasoning as to why the garden should be destroyed. Maybe now they should be reconsidering that mindset in a post-COVID world.”

In the past few days of reopening so many neighbors have expressed such gratitude for Elizabeth Street Garden during these times. We’ve always brought up the vitality of such spaces in cities, but it’s clearer now more then ever. (1/3) #SaveESG #ElizabethStreetGarden pic.twitter.com/u8dRjNav5n

— Joseph Reiver (@ESGEDNYC) July 5, 2020

Indeed, coronavirus-inspired initiatives like Open Streets reflect the city’s commitment to carving out more public space for socially distancing New Yorkers. Tucked unassumingly between Prince and Spring Sts., the Elizabeth Street Garden is located on city-owned property. It was created 30 years ago by Joseph’s father, Allan Reiver, who continues to lease it on a month-to-month basis.

The unique garden — festooned with monuments and architectural pieces — offers locals a quiet retreat from the hustle and bustle of their city.

“With the Department of Education’s cooperation, ESG could serve as a litmus test for the consideration of gardens across the city in confluence with our schools,” Reiver wrote in the open letter.

He pointed to the garden’s existing track record of successful educational programming.

“In 2019, ESG worked with over 750 students from P.S. 1 and P.S. 130,” he wrote. “Over the course of several months, classes visited the garden to learn about plants and seeds, sustainable stewardship, and art through nature. Now, as we recover from the pandemic, we have a new opportunity to preserve and expand upon the educational character of the space.

“Places of beauty, like the garden, they feed the intuition to learn,” Reiver stressed. “It’s a space that fuels creativity. It fuels the need to create and learn.”

Reiver said the Department of Education has not yet responded to the letter, but he plans to reach out to school officials at P.S. 1 and P.S. 130 in the next few weeks.

“It’s important that the city meets this unique situation with unique solutions,” he said. “There are people who will say, ‘No this won’t work.’ But it has worked. New York has a history of teaching outdoors. We can use this time to really expand upon this idea; to see the benefits of learning in nature — particularly nature that exists in an urban environment — during the COVID shutdown and beyond.”

Be First to Comment