BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | As the protests over the killing of George Floyd reached new heights this weekend, Washington Square Park was flooded with thousands of peaceful demonstrators Saturday afternoon.

There were inspirational speeches, poetry, rapping and, above all, a resolve that things in America must change.

Closing out the rally sometime after 5 p.m., two emcees finished by singing, “We callin’ out the violence of these racist police, and we ain’t gonna stop till our people are free.”

The crowd was diverse, yet unified in the goals of stamping out police brutality and creating a more just society.

Everyone wore a face mask, and volunteers circulated through the park handing out PPE.

Among the throng was Henry Adebonojo, 60, a black filmmaker from Queens, who is a veteran of past protests, including over the police killings of Amadou Diallo and Sean Bell. Diallo, a Bronx man who was a vendor on E. 14th St., was unarmed and entering his home when he was slain by cops in a hail of 41 bullets in 1999.

Adebonojo said the protesters’ anger goes beyond Floyd’s killing.

“I think it’s more a young person, 25, 26 years old, recent graduate from college — what are your prospects?” he said. “There’s a level of frustration and, in a sense, of fraternity.” By gathering together and protesting, he said, “People feel that they’re not alone.”

He said he felt the reporting on the violence that marred some protests, along with looting, was a “misrepresentation by the media” and had threatened to derail the effort.

“Forces in the anti-brutality movement took control to keep the message on track,” he noted.

While the protests are clearly dominating the “news cycle,” one has to ask the question, will they have a lasting impact?

“It’s hard to tell,” Adebonojo reflected. “I’ve been around a while. If you asked me in my late 20s, early 30s, ‘Would you be doing this 20 years later?…’ I want to be optimistic. It’s going to take leadership.

“In a way, this is the kind of thing that threatens to destabilize society,” he said. “Either we’re going to work together or… .”

A Filipino-American couple originally from the Bay Area, Jonathan Juntado, 30, and Michelle Raganit, 29, were also in Washington Square on Saturday to show their support.

“There’s always been a saying in the Filipino community, isang bagsak — ‘one fall,’” he said. “It means, ‘if one person falls, we all fall.’”

Juntado said he definitely thinks the protests will change things for the better.

“We’re building a coalition that we haven’t seen anything like before,” he said. “I see it as the civil-rights movement for our generation — millennials — especially for those of us growing up on social media.

“It’s a combination of this with the pandemic going on, Trump in the White House, frustration boiling over.

“The first days of protest were very emotional,” he said. “Now it’s transitioning to how can we ask our lawmakers to take all that emotion [and effect change].”

The momentum will last through the November election, he predicted, hopefully.

Belinda Blum, 52, and her daughter Lou Moonlight had joined a protest in Harlem earlier on Saturday, then marched all the way down to Washington Square.

While the marchers all wore masks, she was upset that very few police had their faces covered.

“I think that something’s happening,” said Blum, who is an artist and teacher, of the nationwide protests. “It was a good thing to know that people could go to protests all day long. People are cooped up.

“Obama said this is the beginning of the articulation of the problem,” she said. “People really need to be active, you need to articulate, and then there will be next steps. I’m paraphrasing Obama.”

While this is an unsettled time in America in many ways, it offers the chance for a reset, Blum noted.

“This particular moment, it’s like a ‘perfect storm,’” she said. “People have lost jobs, lost people. The future is so unknown for so many people. It’s like starting anew.”

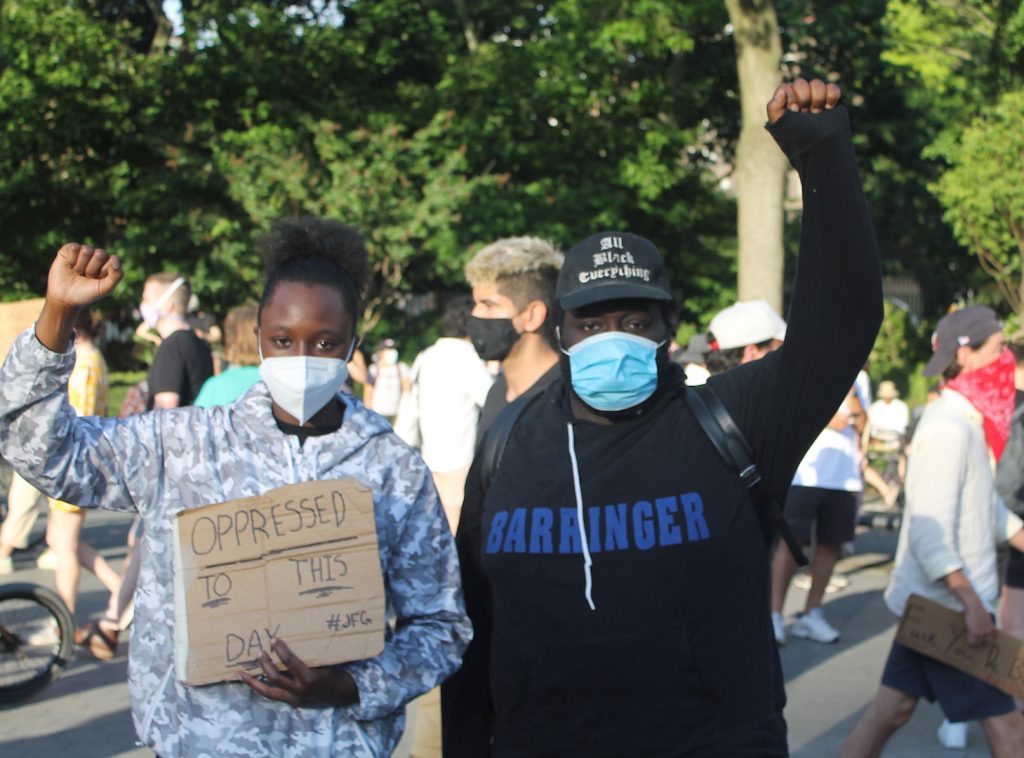

Two young black protesters from New Jersey had already participated in several demonstrations in their home state. Asked if they thought the actions would continue, they said, no question, they must.

“Absolutely,” said Aquil Small, 27, a publicist and writer.

“We have to. We want change,” said his companion, 24, who gave her name as “Anonymous.” A former bartender at Newark Airport, she said she was laid off due to the pandemic.

“Black people built this country for free — and we can unbuild this country for free,” Small declared. “We did a job we were not supposed to do, and then to be mistreated, it’s absurd.”

The woman asked a man who had been handing out goggles if he had any left in his bag, but he was out of them. Small, though, had a pair of clear plastic goggles in his right hand.

Asked if they planned to protest after the 8 p.m. curfew — when goggles might come in handy against police pepper spray — they said, yes, and explained why.

“It’s important to keep protesting after the curfew because we’re letting them know that we’re serious,” Small stressed.

“We have freedom of speech,” the woman added.

Shortly after 7 p.m., many of the remaining protesters marched out of the park and up Fifth Ave. Taking over the streets, they zigzagged up to Union Square, past Gramercy Park and down through the East Village.

They marched eastward down westbound 13th St., then turned onto Second Ave., where a contingent of police on foot and in vans started to trail them down the avenue.

“No justice! No peace!” the protesters chanted, “Hands up! Don’t shoot!” and “Whose streets! Our streets!”

The vans continued to follow them through the East Village.

As the protesters made their way through the streets, people standing on corners raised their fists in salutes, residents in building windows and on fire escapes clanged pots and pans, and drivers honked their car horns in support.

As they rounded a corner onto Avenue A, the protesters cheered as a cooling breeze greeted them, briefly cutting through the mugginess. In the gutter, a small cardboard sign reading, “F— Trump” fluttered. Someone must have seen it because the chant soon rose, “F— Trump!” It doesn’t take much.

The marchers were now making their way along E. Sixth St. toward the F.D.R. Drive. Five days earlier, protesters had occupied the highway down by the Brooklyn Bridge.

Pulling up the rear, walking with a cane, was Bill Pickard, 72, a priest at the Catholic Worker in the East Village. He was asked if he was worried about being arrested for marching after the curfew.

“You always take the risk,” he said. “Have to break the silence, you know. It reminds me of the ’60s when I was involved. It was always the young, the idealistic, that change things — every generation. Today, with Trump in office, it’s like Pilate. I think we’re losing our morals.”

It was around 8:30 p.m. as the protesters hopped a low retaining wall and took over the southbound lanes of the F.D.R. Drive.

Across the highway, youths at a playground in East River Park cheered on the marchers. “L.E.S.!” one of them shouted, for “Lower East Side.”

They walked down the F.D.R. until Grand St., then got off the highway and continued to march around Lower Manhattan. All the while, they were followed by police vans and also a police helicopter above keeping an all-seeing eye on them.

Maybe receiving intel that the protesters would try to take the Williamsburg Bridge, police could be seen at 9 p.m. massed around the foot of the bridge on Delancey St. A cyclist who had just biked across from Brooklyn, said police also had the bridge’s eastern end blocked off.

Asked if police would eventually “kettle” the marchers, an officer on the Delancey St. detail said it depended where they went.

“No more going on bridges or major roadways,” he said. “If they do, they’ll be arrested.”

As of Sunday, Mayor de Blasio had lifted the curfew. He was unapologetic, saying the measure was necessary to stop property damage by radical activists, as well as looting.

Thank you Lincoln Anderson for this thorough coverage of yesterday’s march, and for the great photos. Keep up the pressure!