BY STEPHEN DiLAURO | Anyone wandering into a gallery where artist Jon Tsoi is performing could feel baffled watching him attack a canvas with a rock or a knife while blindfolded.

“Worship the unnamable and unexpected art — the Yin — yet embrace and be indiscriminate toward all art — the Yang. Observe the world and one’s outer surroundings, yet trust one’s inner vision and intuition,” Tsoi says. “As such, I use a blindfold to create art through the inner spirit, which in turn can be absorbed through the eyes.”

O.K. Who can argue with an artist’s self-described motivation? Tsoi told me he follows the philosophy of the Tao, in life and art. Around the world, he has had more than 50 solo exhibitions and participated in more than 100 group shows. He must be doing something right.

A visit to Tsoi’s studio reveals a Picasso-like need to always be surrounded by works from his various periods.

“Picasso is my guiding light as an artist,” Tsoi explains.

The hundreds of canvases created over several decades reveal an underlying style that comes through regardless of the disparate aesthetic explorations and realizations that evolved since Tsoi’s arrival in the U.S. from Sichuan, China, in 1979.

The unique juncture of art and alternative medicine is also center stage when Tsoi performs. That’s because, in addition to being a cutting-edge presence in the New York art world, he is also a doctor of Chinese medicine specializing in acupuncture and herbalism. His wife is also a doctor of Chinese medicine, and they operate two clinics.

He is a frequent participant in the artistic goings-on at Juan Puntes’s White Box Gallery on Avenue B. Other recent venues where the artist has performed include the Copacabana and Ethan Cohen’s Kube, in Beacon, NY. Puntes is one of Tsoi’s biggest supporters. He has arranged exhibits of Tsoi’s work in China, Italy and elsewhere abroad.

Tsoi’s parents recognized his artistic proclivity at an early age and nurtured and encouraged it. However, after high school he was sent to work on a collective farm as part of Chairman Mao’s repressive Cultural Revolution.

“I got very good at it, and I enjoyed the work,” he recalls. “We were living in nature and I drew strength and inspiration from that. It toughened me up and made me able to endure. That harsh environment became a positive force, instilling in me the will to never give up.”

His persistence and focus served him well. He left China and as he tells it, “I saw New York City from the airplane window, and I knew that this place was my destiny.”

He was willing to do whatever it took to survive while creating art. He often sold his early paintings and drawings on the sidewalk in front of various museums around town. He worked as a dishwasher and used his wages to pay for English-language instruction.

“I was a happy artist,” he recalls.

When his parents came to the United States, they were shocked to find their son engaged in menial work to support his artistic career. They insisted he take up the family business, and he became a doctor of Chinese medicine, the fourth generation to do so in his family. One of his adult children is the fifth generation to practice medicine.

For Jon Tsoi, it was a logical segue to incorporate art into his practice of medicine, and vice versa. In 2017, he did a four-day blindfolded performance titled, “Art Diagnosis and Diagnosis for Art,” at the Queens Museum. He used a series of paintings and a process of elimination to diagnose maladies possibly afflicting volunteers from the audience.

“I was 100 percent accurate,” he says. “By using art as holistic medicine, we can all benefit from the mystery of art, balancing ourselves physically, mentally and spiritually.”

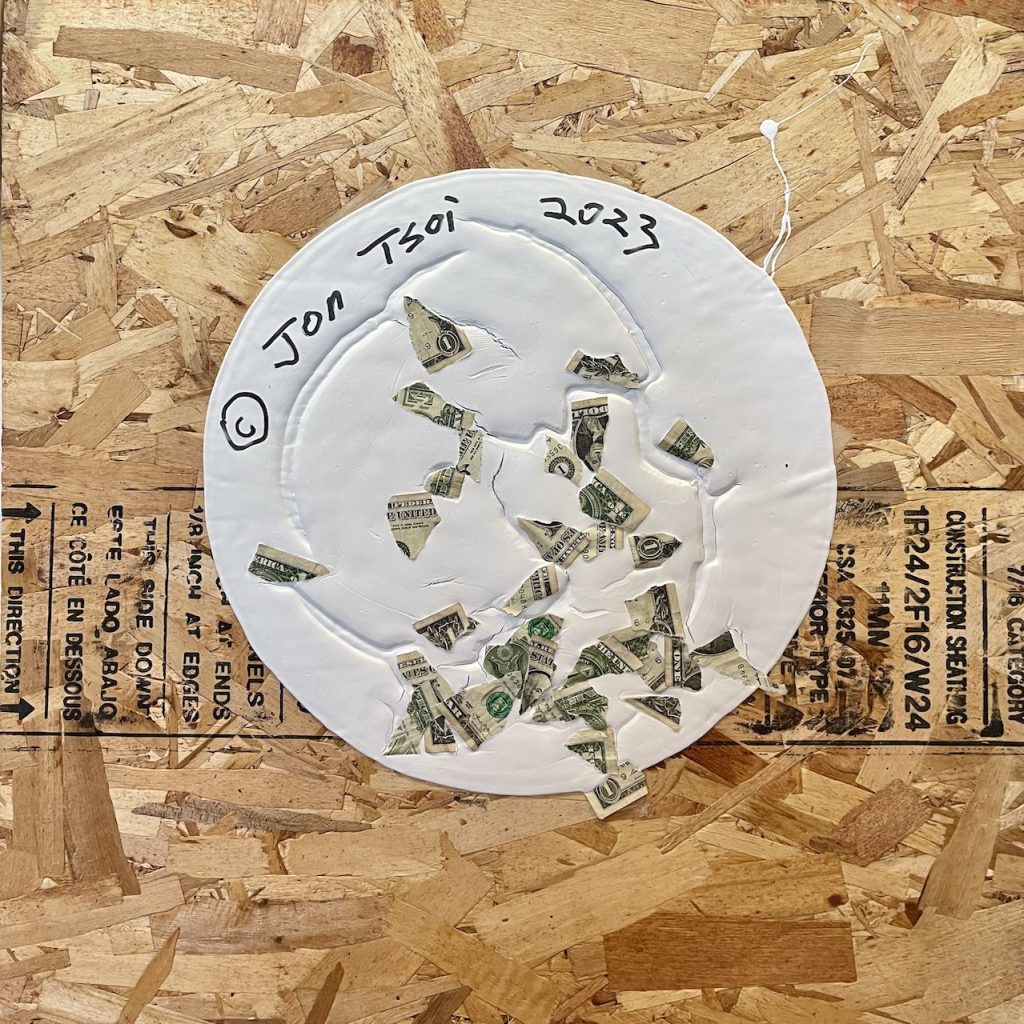

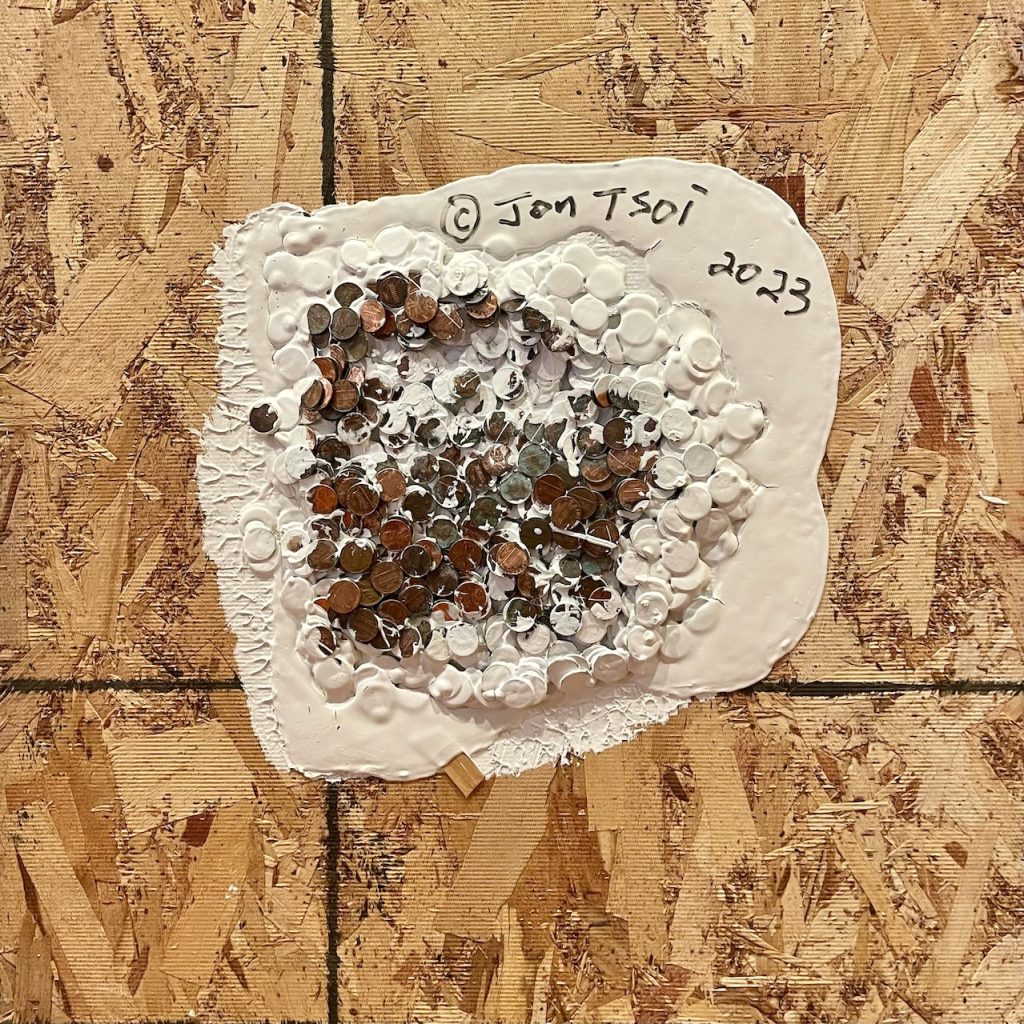

These days the artist focuses his performative painting on healing a world where the current warmongering leaders have gone mad with greed and weapons. He affixes money — both paper and coins — to a canvas as part of his palette. He paints it and then attacks it with a rock or a large knife. At the same time, he shouts words to draw attention to the connection between money and war — a connection seldom if ever examined in mainstream news, other than to report multibillion-dollar weapons packages.

“Jon Tsoi makes powerful and unusual performances that result in powerful and unusual works of art,” says critic and writer Anthony Haden-Guest, who is a central figure in the resurgence of interest in artists who exploded onto the 1980s East Village scene and continue working to this day. Jon Tsoi is certainly part of that nexus.

His performances take place in galleries and nightclubs, such as the famed Copacabana. The resulting paintings and collages can incorporate elements such as ropes, healing herbs, fabric and more, in addition to paint and money. The prices for his finished canvases range from thousands of dollars to six figures. He also has done work on rice paper. This April, he has been invited to create and execute a performance painting at MACRO — the contemporary art museum in Rome, Italy.

With an engaging grin, he says: “I’m still a happy artist.”

DiLauro is a playwright, poet and roving cultural correspondent for The Village Sun.

Be First to Comment