BY HARRY PINCUS | The passing of Wayne Kramer of the MC5 this weekend, as well as the Grammy tribute to Tina Turner, took me back to the long ago. All I could think of while watching the Grammy tribute was the actual Tina, and her magnificent legs, as they pounded the stage like jackhammers, surrounded, of course, by the Ikettes, and the now reviled Ike. I will always see her as she appeared from my vantage point in the balcony of the Fillmore East.

I recently mentioned the Fillmore to someone who lives on Sixth Street and Second Avenue and had never heard of it. This is a shame, and seemed inexplicable until I realized that I was already middle-aged when this person was born. I guess they’ll never enjoy the rice pudding at Ratner’s while watching the entire cast of “Hair” cavorting at the next table, but then again, it’s always wiser to be young, now.

Back in the era of free-form radio, when I was a teenager, my devotional object was a beige AM/FM Panasonic that invited the Beatles, the Stones and the collective cultural explosion into our otherwise desultory existence. The DJ’s had names like Rosko and the Night Bird, and they read poetry in dulcet tones. Rosko debuted Dylan’s “Nashville Skyline” by playing “Lay Lady Lay” 29 times, and when one of the purring DJ’s offered free tickets to see a band called the MC5 at the Fillmore East, I called the radio station immediately, and managed to get tickets.

Some high school pals and I had already ventured into the Cafe Wha? on a Saturday afternoon, and even a head shop or two. The psychedelic posters were thrilling, bathed in black light, and I’d proudly purchased a huge, garish belt buckle in a Kings Highway head shop called the Id, which we called the Yid. It was a first step toward the real exotica of the Lower East Side, and I couldn’t wait for my free tickets to the Fillmore.

My girlfriend had to come up with an elaborate scheme to escape her parents, and when she and I emerged from the subway kiosk at Astor Place, we entered another world. The Summer of Love was ending, but the seed of revolution had been firmly planted.

A friend told me a story which describes the scene back then. He was getting high and drinking wine with some junkies and street people in front of St. Mark’s Liquors at about 4 in the morning, when a young woman in feathers and furs approached the group. She seemed kind of agitated when she realized that the liquor store was closed, and asked the group if they knew of a liquor store that might be open. One of the junkies laughed at her, and said, “Yo, honey, there ain’t no all-night liquor stores.” The woman in feathers and furs asked if she could share a hit on his bottle, and was once again rebuffed. Finally, my friend stepped in.

“C’mon,” he said, “give her a drink. That’s Janis Joplin.”

I was a clean-cut 16 years old when my girlfriend and I marched wide-eyed down St. Mark’s Place, past the Diggers’ Two Dollar store, the sitar store and the old Balloon Farm, which was now called the Electric Circus. Gem Spa, a corner candy store known for its egg creams at the corner of Second Avenue, had by now become a nexus of hippies, winos, speed freaks, bikers, runaways, narcs and bug-eyed tourists.

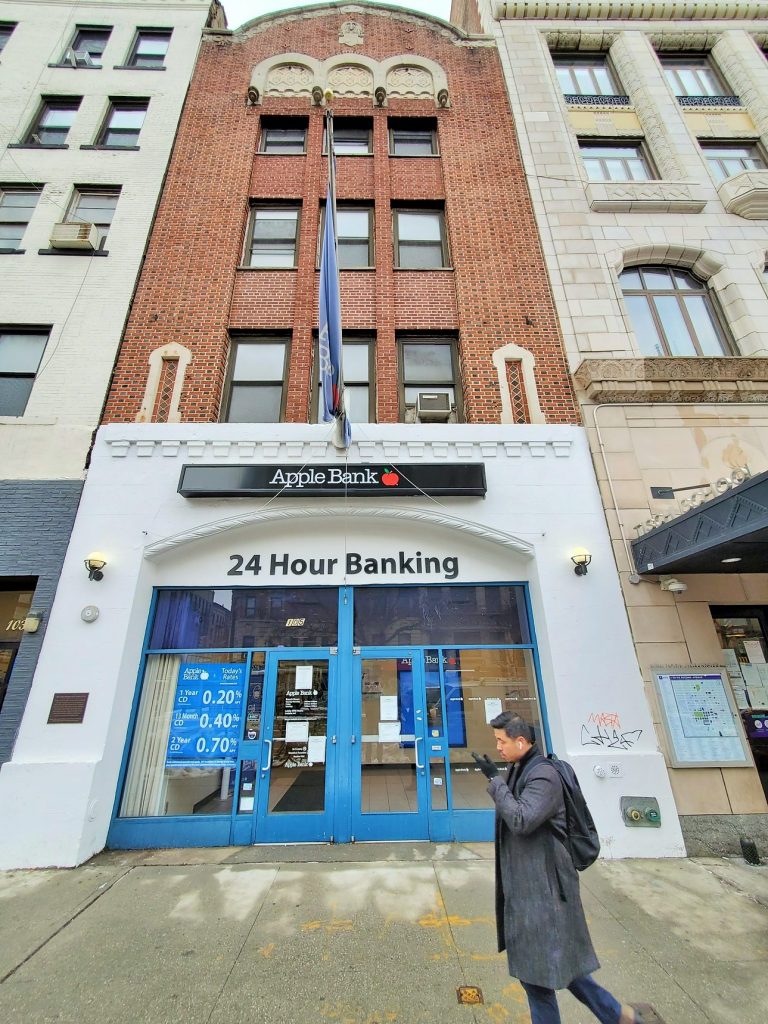

Exhilarated and terrified, we hustled down Second Avenue toward Sixth Street and the temple of rock that was the Fillmore East. It had opened in 1925 as The Commodore Theatre, designed in the Medieval Revival style as one of the many theaters along the Yiddish Rialto that was Second Avenue. By now it was the reclamation project of Bill Graham, a tough Holocaust survivor who fled destruction as an 8-year-old, wore a wristwatch on each wrist, and didn’t hesitate to issue blotta boy commands to the likes of Jimi Hendrix, the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead. A blotta boy was a gangsta in Yiddish, and Bill Graham was all of that and then some.

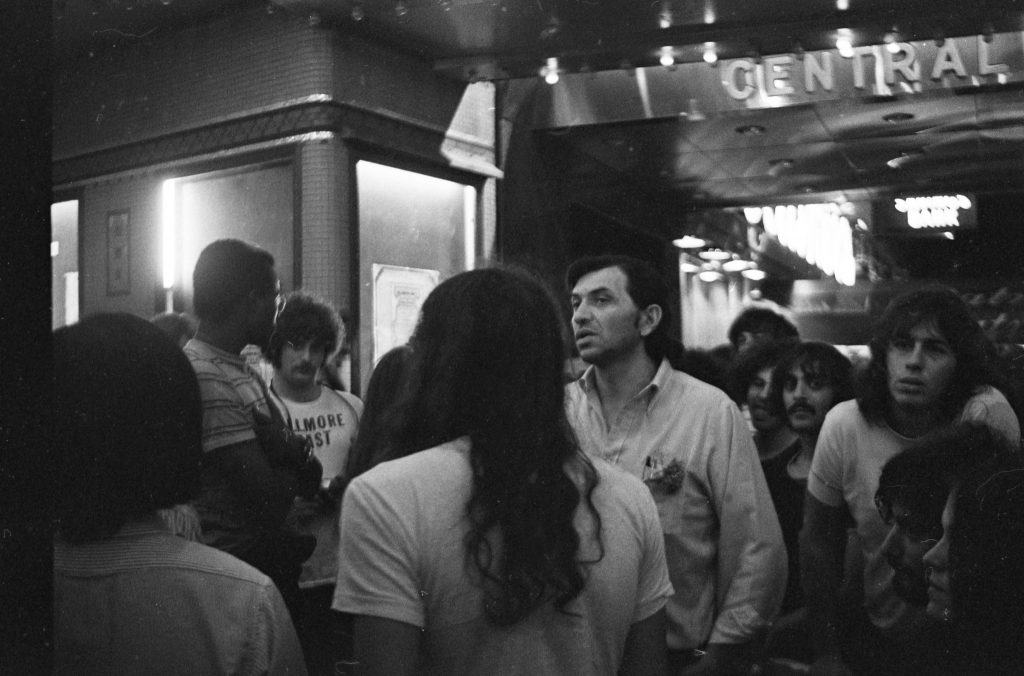

I’d heard the MC5 anthem, “Kick Out the Jams,” but it didn’t mean as much to me as the melting, womblike reality of the Fillmore itself. We were surrounded by throngs of kids who were as excited as we were to get free tickets from the radio station. The Fillmore was inundated with teenage girls in bellbottoms and furs, weed sellers, acid trippers, macramé weavers, runaways, speed freaks, guitar freaks and all manner of stoned freaks.

Unbeknownst to us, the radio promotion had provoked a turf battle between Bill Graham and a neighborhood collective called the Motherfuckers. The conflict revolved around the profit motive and the offbeat rock entrepreneur, who was threatening to turn a profit out of the old Yiddish theater. The neighborhood bikers and flower children promoted anarchy and opposed capitalism. A free benefit at the Fillmore for the Columbia University strikers, featuring a performance of “Paradise Now” by the Living Theatre, had devolved into a disaster when Bill Graham told the incensed audience, “The theater belongs to me, because I pay the rent.”

We strode excitedly past the pot dealers and speed freaks, and into the exotic old Yiddish theater lobby, which was dimly bedazzled with colored lights and a panoply of feathered hippies in all their finery. Everything was a blur, and the swirl of lights grew even dimmer as the smell of weed and patchouli oil thickened on each level, as we approached our appointed seats. The theater was amazingly high — the seating, I mean — and yet you weren’t very far back from the stage. The Fillmore was ornate, dark and extremely mysterious, and I wondered who might have performed here, or if my beloved grandfather had once sat in this house.

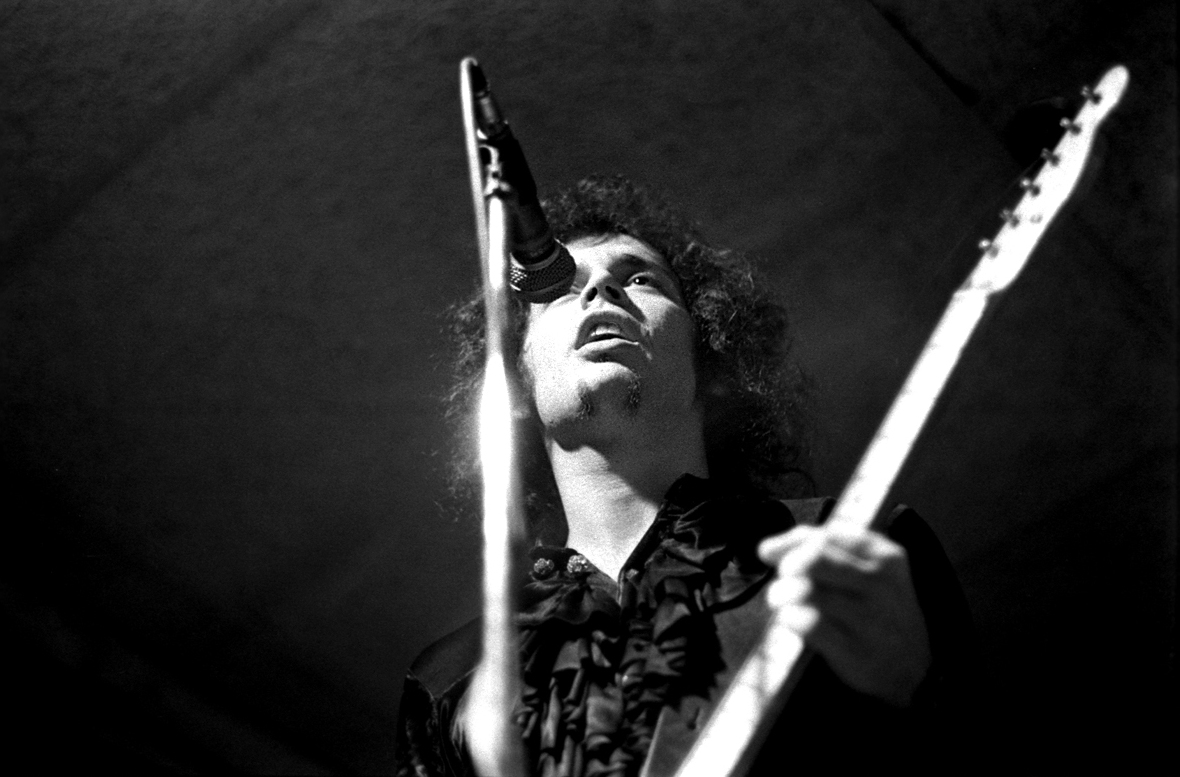

The MC5 was a ferocious band of revolutionaries out of Lincoln Park, Michigan, featuring Wayne Kramer and Fred “Sonic” Smith, future husband of Patti. Influenced by Beat poets, Black Panthers and a White Panther named John Sinclair, they must have sympathized with the Motherfuckers over Bill Graham’s profit motive.

Just as the music was about to begin, the doors of the Fillmore flung open with a thunderous crash and Bill Graham, who had been personally guarding the place, had his nose broken by The Motherfuckers, who knocked him out with a chain. They streamed up the aisles toward the stage, where they began wailing away at the MC5 with their clubs and chains. When the assault had finally subsided, the MC5 roared into their iconic “Kick Out the Jams,

Motherfucker” and the concert was on!

I couldn’t believe it, and I couldn’t believe that I had brought my girlfriend, an innocent 15-year-old from Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, to this place. I eventually assumed that the whole thing had been some sort of a dream, but it was actually a fabled event. Rolling Stone magazine reported that the concert concluded when Bowery bums, winos and stick-wielding 11-year-old children ran wild onstage, after the band fled Uptown in a limo destined for Max’s Kansas City.

Every generation has its heroes and myths, and the sweet syrup of nostalgia goes down as easily as an egg cream from Gem Spa. For three bucks we saw Elton John jumping on his piano until dawn, and Eric Clapton onstage with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends. Was our music really better than what I heard on the Grammys? I don’t know, but it’s probably unfair to open any random page of lyrics from Bob Dylan and compare it to what we hear today.

Pincus is an award-winning artist and longtime Soho resident. This is an excerpt from his upcoming memoir, “Artist Proof.”

For more on the legendary Fillmore East, read The Village Sun’s article on Frank Mastropolo’s book, “The Fillmore East: The Venue That Changed Rock Music Forever.”

Be First to Comment