BY LINCOLN ANDERSON AND PHILIP MAIER | At noon on Oct. 11, a Fire Department ladder truck stood parked outside New York University’s Brown Building, a block east of Washington Square Park. The ladder was extended up to the building’s sixth floor.

That was as high as fire ladders went back in 1911, when 146 garment workers, mostly young immigrant women in their teens and 20s, perished in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Today, more than 100 years later, it remains America’s deadliest workplace accident.

On this day, American red-white-and-blue bunting hung from windows on the building’s ninth floor. The fire was sparked, it’s believed, by a tossed match or cigarette butt on the eighth floor — and it engulfed the eighth, ninth and 10th floors. But it was mostly the workers on the ninth floor who died. Fleeing the raging blaze, many leapt to their death on the street below.

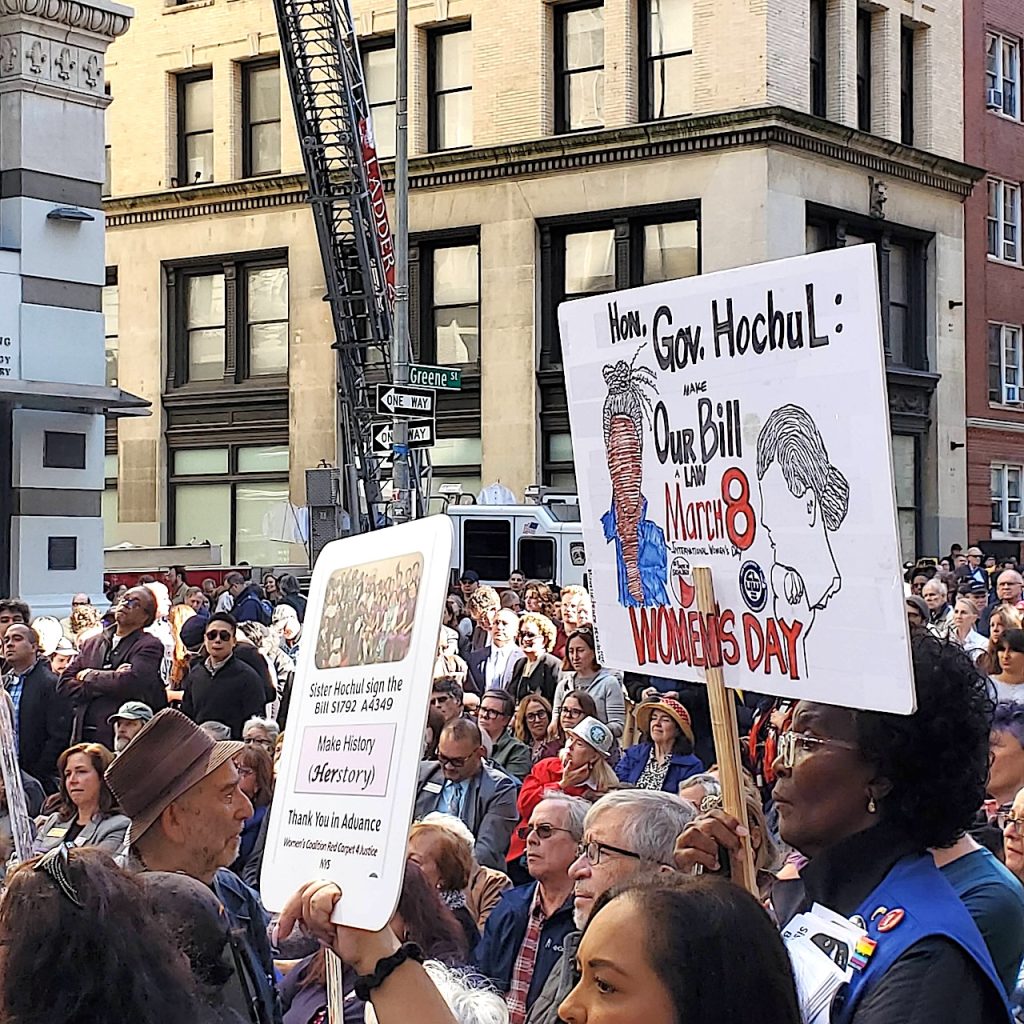

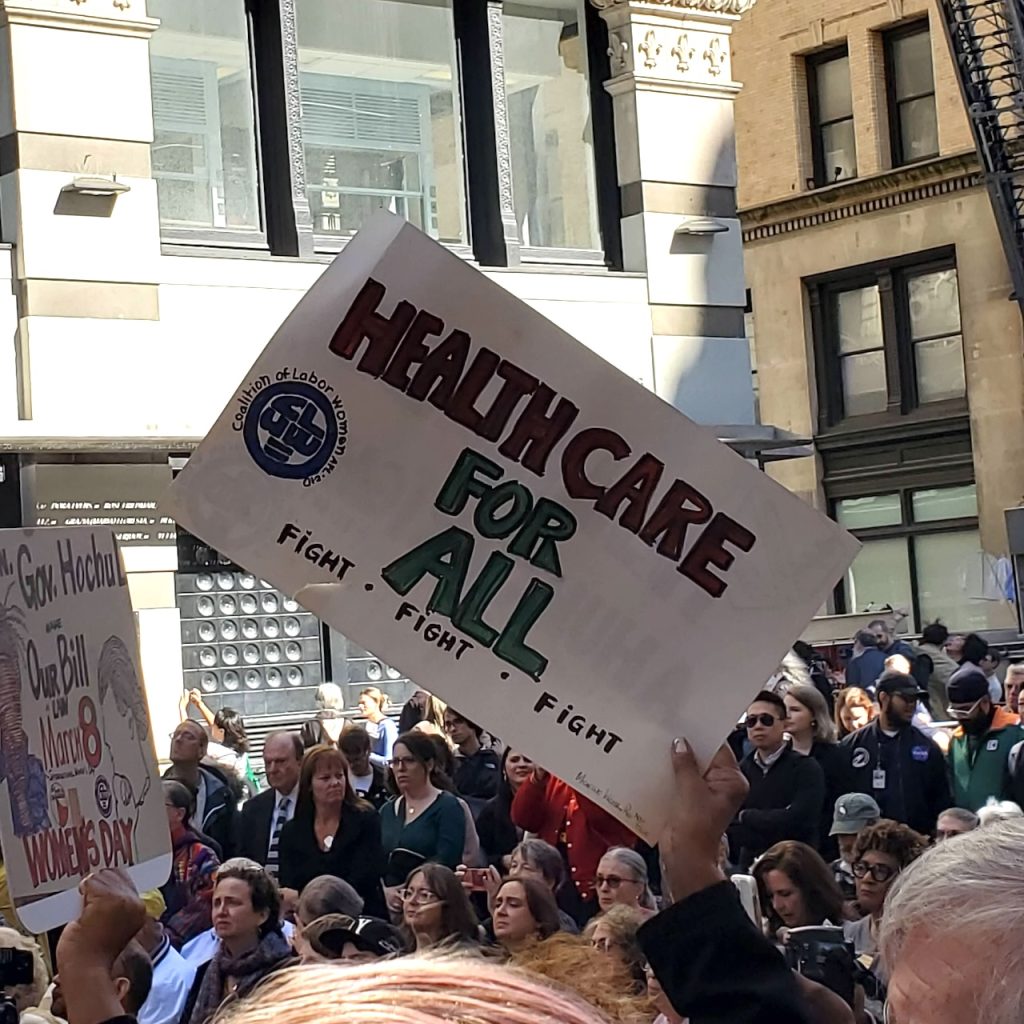

The occasion for the fire truck — and for the hundreds of people who thronged the intersection at Washington Place and Greene Street — was the dedication of a long-delayed memorial to the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. Among them were 125 family members of the victims. The crowd’s numbers were also swelled by many proud union members.

The memorial — which rings the building’s base and will eventually include a metal “ribbon” running up its corner — was conceived and executed by The Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition. The group’s board of advisers includes victims’ family members and union members, among others.

The project was on track to move forward when the COVID pandemic struck, setting it back a few years. The plan is for the metal ribbon up the building’s side to be installed before March 25, the 112th anniversary of the tragic fire.

Governor Hochul was among the speaker’s at the dedication ceremony. She proudly cited her family’s working-class roots.

“My grandfather worked at the burning-hot coke ovens at the Bethlehem Steel plant,” she said.

“These were little girls, young people,” she said of the Triangle victims. “We say, Never again.”

Hochul noted that the young working women at that doomed factory made “shirts for the wealthy to wear in the parks and on Sunday.”

The governor drew a parallel with the massive wave of immigrants who continue to pour across the U.S. southern border, many of them making their way to New York City in search of economic opportunity.

“They are here to work,” she said, before repeating, “Let them work! Let them work! Let them work! … We need them!”

New York is the birthplace of the worldwide labor-rights movement, she noted.

Mary Anne Trasciatti, president of The Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition, said the memorial finally represents “a tangible site for collective memory and collective action” in the fight for “fair wages, decent benefits and safe working conditions”

She praised Triangle Fire descendants — her family lost a member in the conflagration — for their financial support and volunteer efforts: “Their memory has been an inspiration and their pain has been an invaluable force in making this dream a reality,” she said.

“Last but not least, let’s hear it for the SAG/AFTRA, UAW…union members on strike,” she declared, “and for those struggling to unionize at Starbucks, Amazon, Trader Joe’s and other nonunion workplaces. We stand with you in solidarity!”

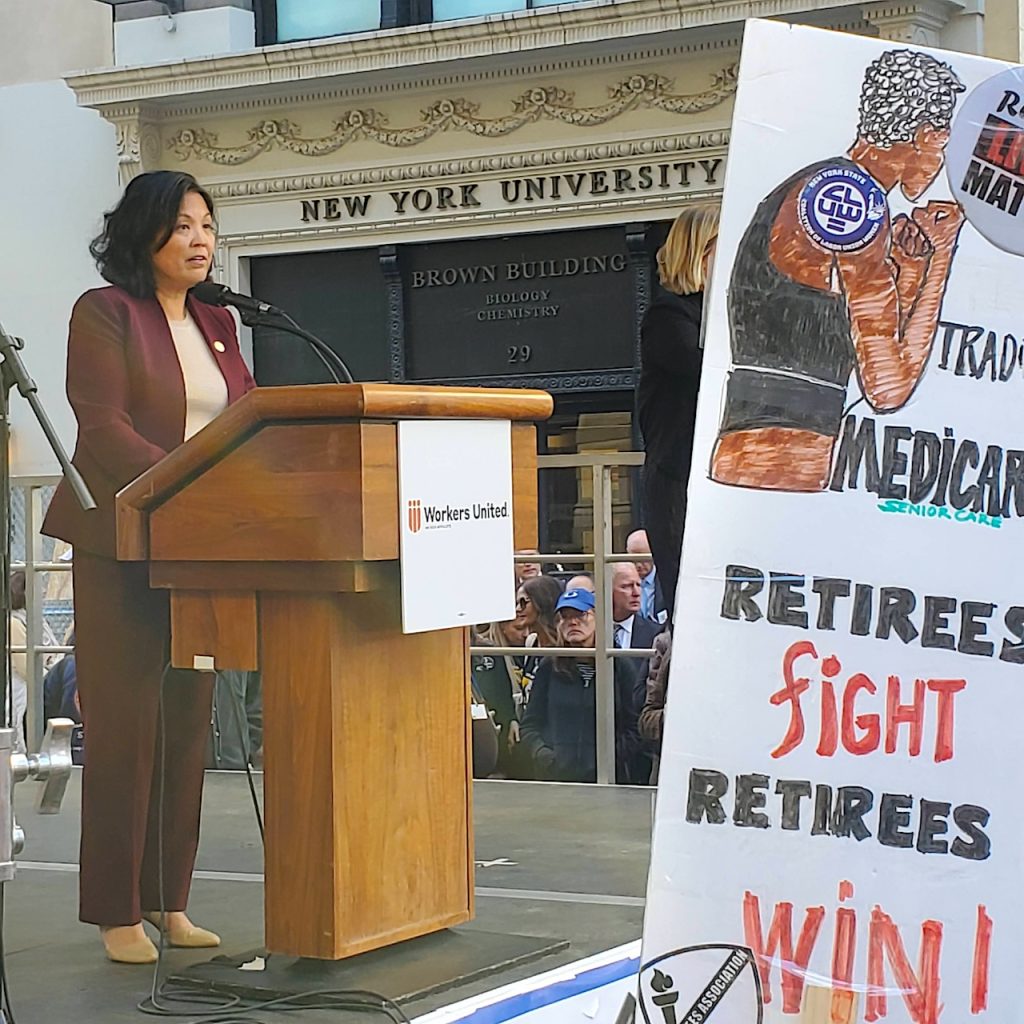

Also among the speakers was Julie Su, acting U.S. secretary of labor. Su noted how Frances Perkins personally witnessed the Greenwich Village disaster in 1911, before eventually going on to become secretary of labor under F.D.R., during which she developed the Social Security program, fought for the minimum wage and against child labor.

Su said that, like F.D.R., Joe Biden is a “transformational president” on labor issues. Calling him “Union Joe,” she said Biden is “the most pro-worker, most pro-union president in our nation’s history.”

The acting secretary recalled how one of the Triangle victims gave a speech — that no one could hear — before jumping to her death.

“If only we had heard the striking workers when they were marching in the streets years before,” she said, “when they were demanding better wages and safe working conditions.”

After the ceremony, people lined up to look more closely at the memorial. Among them was Deborah Gardner from Brooklyn. She said her grandmother, Nettie Gruber — then a 17-year-old immigrant from Odessa — somehow managed to survive the horrific inferno.

“All she would say is a young man let her and her sister out,” she said. “But she never wanted to tell what happened. She never wanted to talk about it.”

After the disaster, her grandmother continued in the garment industry.

“She made clothes for me as a little girl,” she recalled.

Gardner, who is a historian, echoed Su and Hochul in noting that the fire changed the course of America — and the world.

“Frances Perkins saw this,” she said. “She said, ‘This was the day the New Deal was born.’ We got Social Security, unemployment insurance… .”

Though he is not a Triangle descendant, Kevin Baker, a bestselling author, is on the coalition’s board. One of his novels, “Dreamland,” climaxes at the Triangle Fire. He wrote the inscription that’s on the memorial — in English, Italian and Yiddish. On Oct. 11, after the ceremony, Baker was handing out the coalition’s commemorative booklet.

“One hundred forty-six people died in the space of about 15 minutes,” he related. “The building was fireproofed — it still stands — but not everything in it. The owner used to have regular fires at the end of the year, to get rid of their leftover lawn — fabric was called “lawn” — and charge their insurance.

“What they think is one of the cutters dropped a cigarette butt into one of the fabric piles,” he explained. “They used to lock all of the doors and make the women walk through one door, so they wouldn’t steal any fabric.”

On March 25, 1911, as Baker explained, everyone got out safely from the 10th floor, almost everyone got out from the eighth floor, but almost everyone on the ninth floor died because the doors were locked.

“Joseph Zitto, the elevator operator, was the hero,” he said. “Joseph Zitto kept going back up until there were too many bodies on top of the car.”

Presciently and tragically, the Jewish Daily Forward on Jan. 10, 1910, wrote: “The ‘Triangle’ company… . With blood this name will be written in the history of the American workers’ movement, and with feeling will this history recall the names of the strikers of this shop — of the crusaders.”

Rather than the workers being remembered because of bloody anti-union violence, they are remembered for being victims of a fire that changed the course of American labor and political history.

The volunteer nonprofit The Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition has raised funds toward the memorial’s $2.4 million cost. The group was founded in 2008 to educate the public about the fire and create a permanent memorial to the workers who perished that day. The memorial was funded through grants and by donors, unions and the fashion industry. Donors of $25,000 and above are listed on a plaque commemorating the victims, all of whose names are also listed.

In 2018, under Governor Cuomo, New York State provided a $1.5 million grant for the memorial. The memorial’s design, by Richard Joon and Uri Wegman, was chosen after an international competition. The coalition received 180 proposals from around the world, which then went through a juried selection process. The project was approved by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and Community Board 2.

New York University helped assist and coordinate events for the families and the memorial.

Beyond the completion of the memorial, the coalition intends to remain active — both to plan the annual remembrance and to raise public awareness about the fire and its continuing relevance for worker rights and workplace safety.

An unsung hero is Michael Hirsch, a dogged investigator who worked relentlessly to contact the descendants prior to the fire’s 100th anniversary and identify the burial location of some of the victims. Hirsch contacted Philip Maier, one of the writers and photographers of this article, and his family to confirm that they were related to Rose Oringer, Maier’s great-aunt, who died at 19.

Suzanne Pred Bass, a coalition board member, had two great-aunts who were working at the Triangle Factory that fateful day, Rosie and Katie Weiner. Katie made a harrowing escape — grabbing onto the elevator cable on the final car down — while Rosie perished in the flames.

“People want to recognize the significance of Triangle,” she said. “Young people, immigrants and women in so many places are affected by this event, which resonates today. The same issues of workplace justice and equality are present. People know the tragedy and what it spawned. The memorial speaks to the distance we have come and where we still need to go.

“May their memories be a blessing.

“May their souls rest in peace.”

Excellent article, Phil and Lincoln. Thank you for helping readers understand the historical significance of this event. Out of a terrible, heart-wrenching tragedy came tremendous progress for workers’ rights and a safer social network. I am sorry for the loss of your great-aunt and the 145 other workers who perished on this day of horror, Phil. Thank you for your part in keeping the light of memory shining.