BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Much of Tom Fox’s life has been spent relentlessly advocating for public open spaces, particularly along the waterfront. Although perhaps less well known publicly, another thing he is very passionate about is his photography.

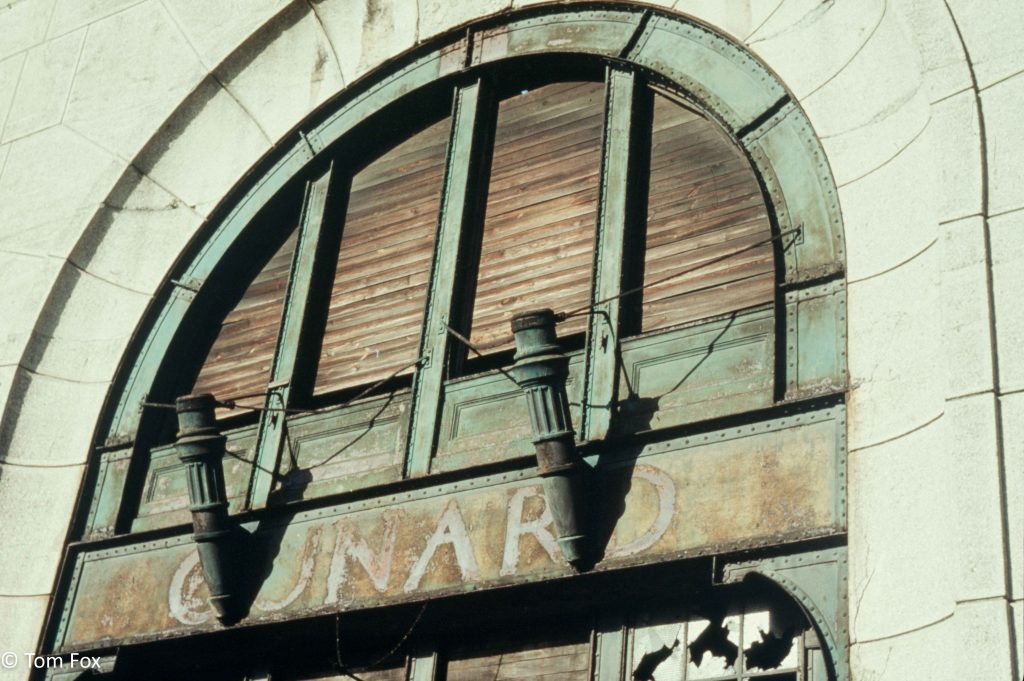

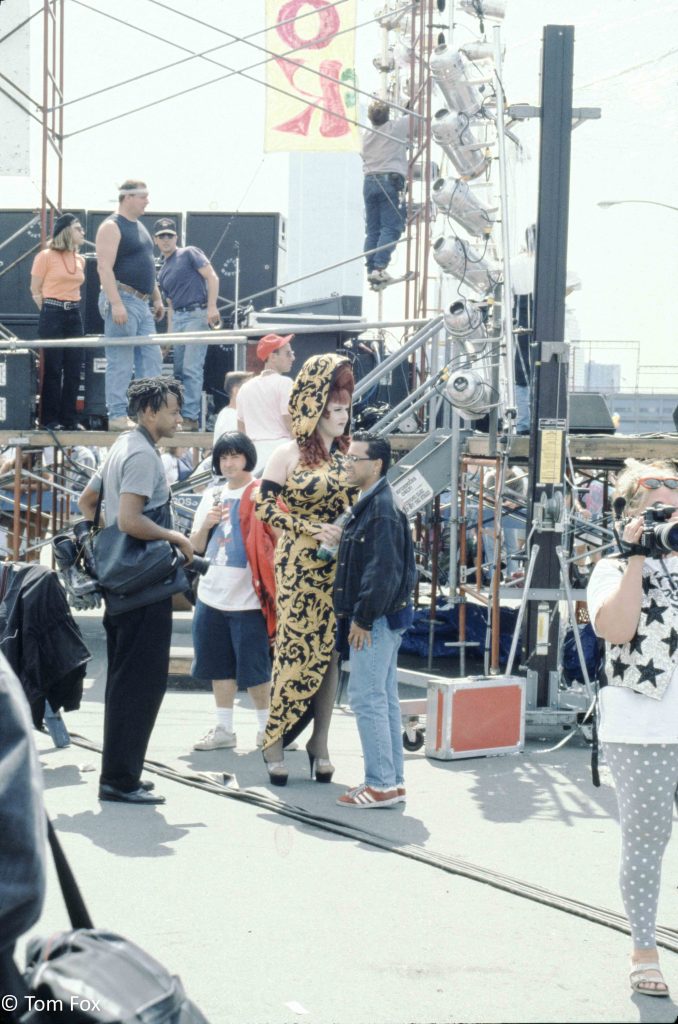

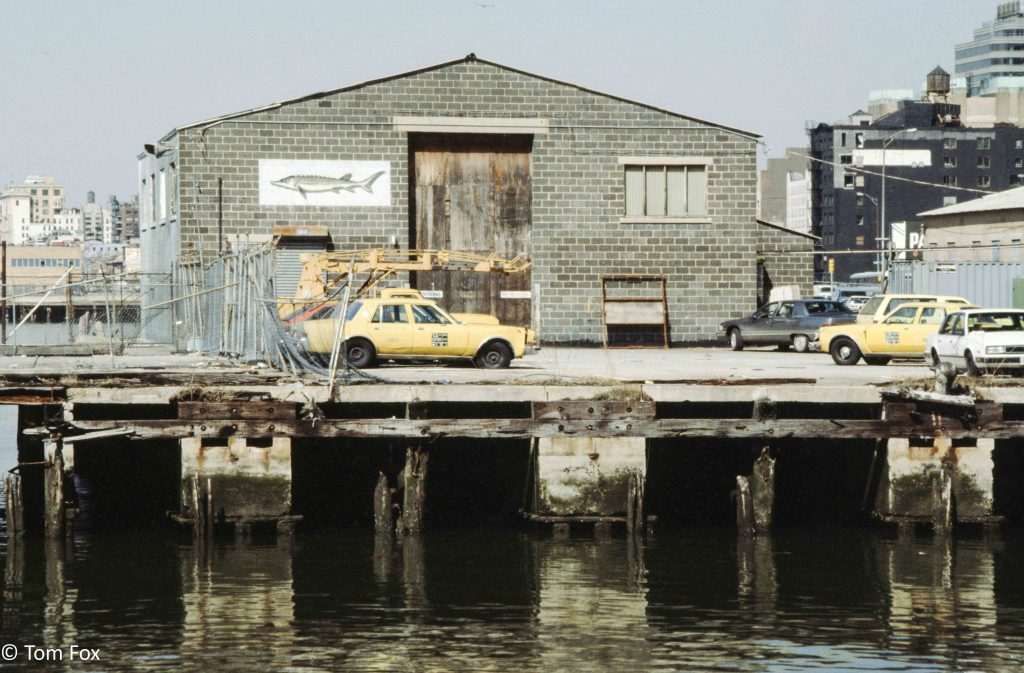

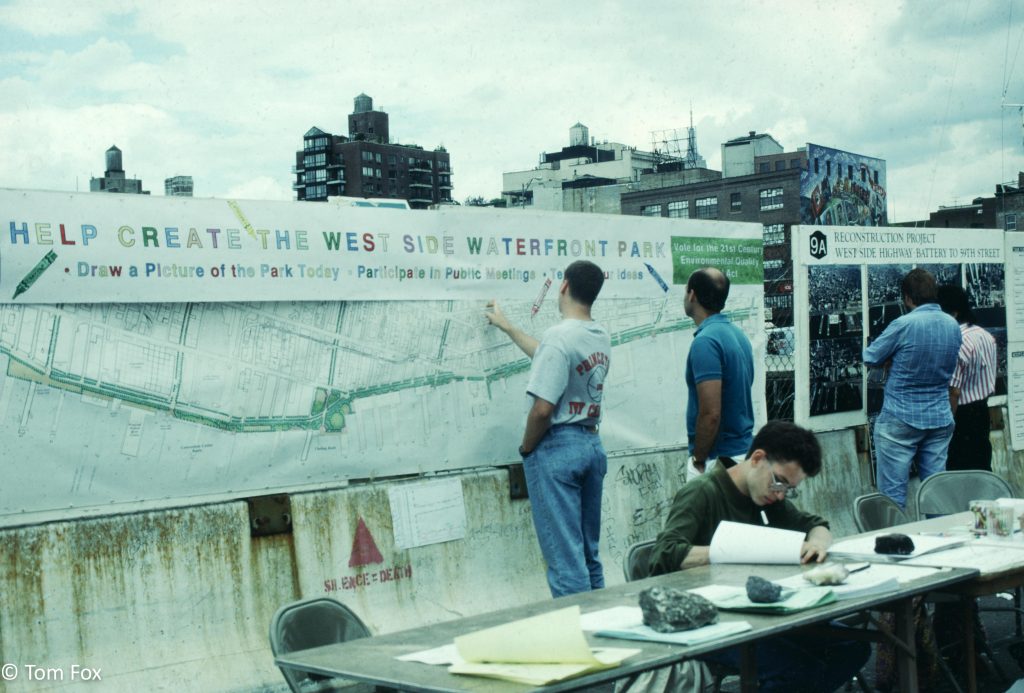

Finding himself living on Bank St. in the early 1980s, he was drawn to the Hudson River waterfront and its broken-down piers — both as an advocate for the creation of the Hudson River Park and as a documentarian, wanting to record the unique scene of a historic area in transition. (The photos in this article were taken roughly between 1986 and 1992, according to Fox.)

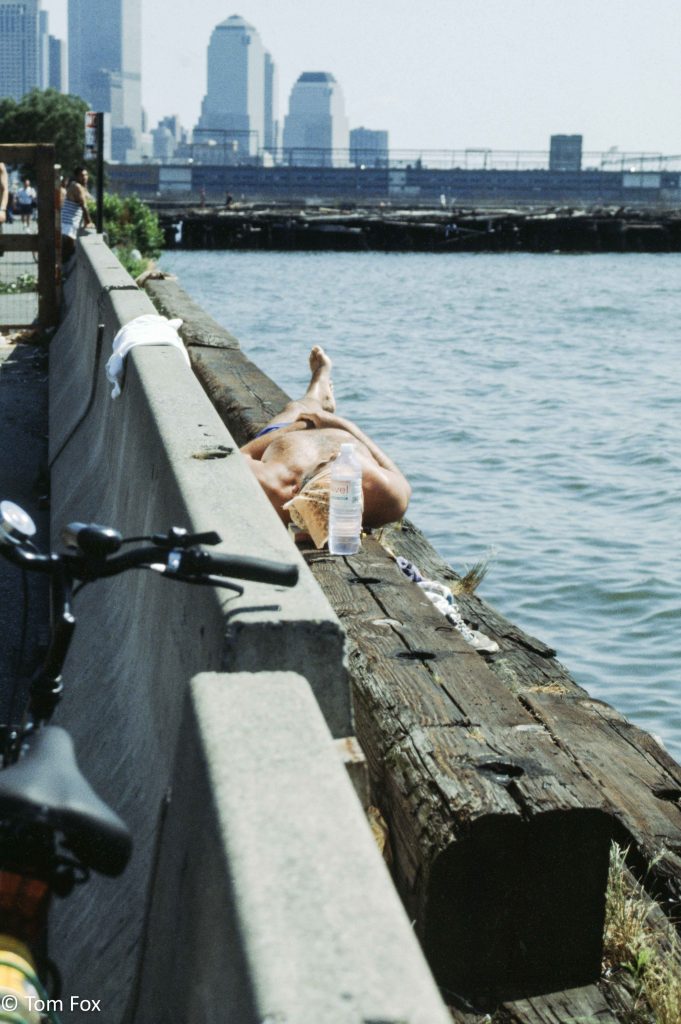

Sunning on a Village pier. (Photo by Tom Fox)

After growing up in Flatbush, Brooklyn, Fox served in Vietnam in the 1960s. It was actually there that he first got into photography.

“I got a camera in Vietnam, at the PX,” he recalled, using the term for a military store.

It was an Olympus, though he’s used Nikons ever since then.

After an honorable discharge, he returned home to get a degree in field botany from Brooklyn College.

Fox went on to work as a ranger at Brooklyn’s Gateway National Recreation Area, leading environmental and high-school educational programs, and also continuing his photography.

“Very interested in nature and the city,” as he put it, he next co-directed a federally funded community garden project in the South Bronx.

In 1978, Fox moved to the Village. Two years before, while still living in Brooklyn, he had joined a new grassroots gardens group, the Green Guerillas. As its vice president, he was the right-hand man to its president, Liz Christy. Fox helped plant the now-massive metasequoia, or dawn redwood, in the Liz Christy Garden, at E. Houston St. and the Bowery.

In 1981, Fox went on to found the Neighborhood Open Space Coalition, including 110 member organizations, serving as its executive director, focused on protecting and expanding the city’s parks and open spaces through research, planning and advocacy.

He was by then around age 35 and living in the Village on Bank St., just a couple of blocks from the Hudson River, after having spent a few years at Sullivan and Houston Sts. Back then, the major neighborhood cause was the fight to stop Westway. The hated megaproject — ultimately scrapped in 1985 — would have added 220 acres of landfill south of W. 40th St., with a highway in a tunnel located where the ends of the piers are.

“I started out as a Westway opponent,” Fox said of his involvement with the waterfront that would eventually see him become a major player in the creation of Westway’s replacement — the Hudson River Park.

He enjoyed the freewheeling West Side waterfront of that pre-park era. The soon-to-be-demolished elevated Miller Highway, for one, was closed to cars and was a cool spot for jogging and cycling, sort of like a barebones High Line.

“My favorite date,” Fox recalled, “was to get a bottle of wine and cheese and bike down the Miller Highway to the Staten Island Ferry, go across to Silver Lake Park, and you could look back and see Lower Manhattan all in gold [in the sunset]. I did it three times. That’s how I would impress the ladies,” he quipped.

He also became vice president for a spell of the Bank St. Block Association. However, Fox said fellow block association leader Bill Bowser later disowned him after Fox became a supporter of the new Hudson River Park project.

In 1987, Fox got married and moved back to Flatbush.

In 1992, Fox would go on to be named president of the Hudson River Park Conservancy — the predecessor to today’s Hudson River Park Trust — the entity tasked by the governor and mayor with overseeing the creation of a new 4.5-mile riverfront park between Chambers and 59th Sts.

During his time on the Conservancy, a thorny issue they faced was people getting onto the dilapidated piers, posing a danger to themselves as well as others. The Conservancy would put up chain-link fencing to keep people off the piers, but before long, a hole would be cut in the fence. Fox hit on a solution, which was to cut away the first 30 feet of the pier. This was done on Pier 49, at Bank St., at the end of Fox’s street.

“Guys would barbecue on the piers,” he recalled. “The piles were coated with creosote. They’d dump the coals and it would ignite the creosote. A fireman got injured responding to a fire during the day. He broke his arm.

“I got chewed out by [Assemblymember] Deborah Glick and a guy with a dog collar when I cut Pier 49,” Fox recalled. “They said, ‘This is a very important pier.’ It was a condemned, dilapidated, dangerous pier. A fireman had gotten injured.”

Under the Hudson River Park plan, some piers, like Pier 49, were not rebuilt. But Fox called his technique of removing the pier’s first part “pier banking,” since these piers could actually someday still be rebuilt — if there is ever the money to do so. Although the piers’ decking has been removed, since the piles are still there — it’s called a “pile field” — it’s like a placeholder in the water and the pier could be rebuilt “in kind,” as it’s called.

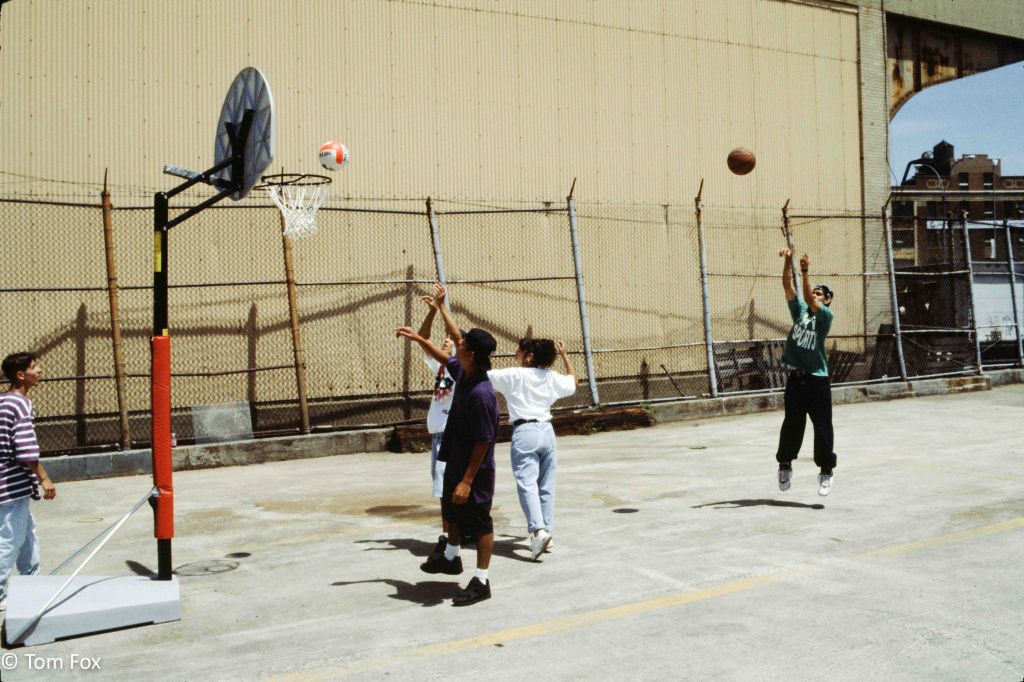

The opposition to cutting Pier 49 showed how much people loved using the waterfront. Fox documented this feeling in other photos, such as of people huddling under the shade of a small tree by a Jersey barrier or elsewhere along the rundown waterfront.

“It just showed people need open space,” he said. “The Village and Tribeca were ranked at 57th and 58th out of the city’s 59 community boards in terms of open space.”

Later on, as a board of member of the advocacy group Friends of Hudson River Park, Fox fought to get illegal municipal uses out of the park, such as the Department of Sanitation garage on Gansevoort Peninsula and tourist helicopter flights at the W. 30th St. Heliport.

From 2001 to 2011, he operated New York Water Taxi, New York’s first intra-city waterborne transportation system, as part of which he initiated the ferry service to the IKEA store in Red Hook, Brooklyn.

More recently, Fox was notably a litigant in The City Club of New York’s lawsuit against Barry Diller’s extravagant Pier 55 “entertainment island” project, at W. 14th St. Fox and his co-plaintiffs battled the plan on environmental grounds, and it was dead in the water. But Governor Cuomo brought the parties back together and revived the project, while vowing to fund and finish the construction of the rest of the Hudson River Park.

Today, living — on the water, of course — in Breezy Point, at the western end of Rockaway, in Queens, Fox is president of Tom Fox & Associates, consulting on urban park, waterfront and maritime projects.

And he’s writing a book. With the working title “How the West Was Won” (Rutgers University Press), it’s an eyewitness history of the effort to create the Hudson River Park.

Not surprisingly, it will feature plenty of his archival photos.

For more on Tom Fox, check out this Vimeo piece about him done by graduate students at Columbia University’s School of Journalism about five years ago.

The Village waterfront circa 1980s to ’90s. (Photo by Tom Fox)

The prison barge at Pier 40. (Photo by Tom Fox)

The pile of road salt at Gansevoort Peninsula, in background, with the former incinerator’s smokestacks, at left, and the World Trade Center in the distance. (Photo by Tom Fox)

Be First to Comment