BY CASEY EPSTEIN-GROSS | One of the first things you see when you enter the Whitney Biennial on the sixth floor of the Whitney Museum of American Art is a hazy sheet hanging from the ceiling, separating you from five photographs on the opposite wall. Through the gauzy grayness, you can make out the basic outlines of faces.

The second thing you see at the Whitney Biennial, as you step around the divider: the portraits themselves, no longer obscured by the haze. The faces staring back at you in this installation by the artist Daniel Joseph Martinez prompt a sharp double take: These photo-realistic people whose vague shapes you saw through the curtain are actually brutal and grotesque, exercises in media-inspired body horror. Skin is melting, eyes are scabbed over, sharp teeth stick out from dry lips.

One is Dracula, one an alien from “The X-Files,” one is even a cyborg. How did you mistake these Frankenstinian creations for humans? You step back behind that hazy curtain to answer this question and realize with unease that it was not a hard mistake to make: From a distance, obscured by hanging material, and subject to only a quick glance, these monsters are indistinguishable from seeing one’s reflection in a particularly foggy mirror.

The experience of entering this year’s Whitney Biennial is akin to the experience of the Biennial as a whole: a peeling back of the perceived humanity we see in the world around us to find the horror and tragedy lying underneath, right there in plain sight but only if we blink our eyes to clear the fog.

Many pieces in the exhibit reframe worlds we thought we knew: the digital landscape of “Grand Theft Auto” (Jacky Connolly’s “Descent Into Hell”), familiar scenes from the theatrical canon (Kandis Williams’s riff on Arthur Miller, “Death of A”) and even the uses of household objects (Dave Mckenzie’s “Accessories”).

Despite the great variety of the pieces included in the Biennial, many seemed to share a similar goal: to turn the known into the unknown and the unknown to the known.

Drawing especially on innovative uses of video art and multimedia installations, this year’s Biennial, “Quiet As It’s Kept,” forces museumgoers into a reexamination of the world around them, immersing them in a microcosm of the tumultuous events of the past two years and the upheavals in societal understanding they have brought on.

As a whole, the exhibit grabs you by the shoulders and, again and again, forces you to look at your own world in a new light — a light that others may see daily, but you have never known.

For instance, in one video installation, Alfredo Jaar’s “06.01.2020 18.39,” you’re thrust into the middle of a Black Lives Matter protest that occurred in June 2020 in Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C., while massive fans begin to buffet you with wind as the terrifying sound of whirring helicopters grows louder and louder all around you.

In Coco Fusco’s haunting video piece “Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word,” you find yourself sailing around Hart Island, New York’s potters field, or public cemetery, where prisoners buried COVID victims in mass graves during the height of the pandemic.

In Emily Barker’s piece “Kitchen,” the viewer confronts ordinary kitchen counters that are constructed at a disorienting, exaggerated height, placing traditionally able-bodied viewers in the position of people like Barker (who uses a wheelchair), who must navigate a world that is not built with their needs in mind.

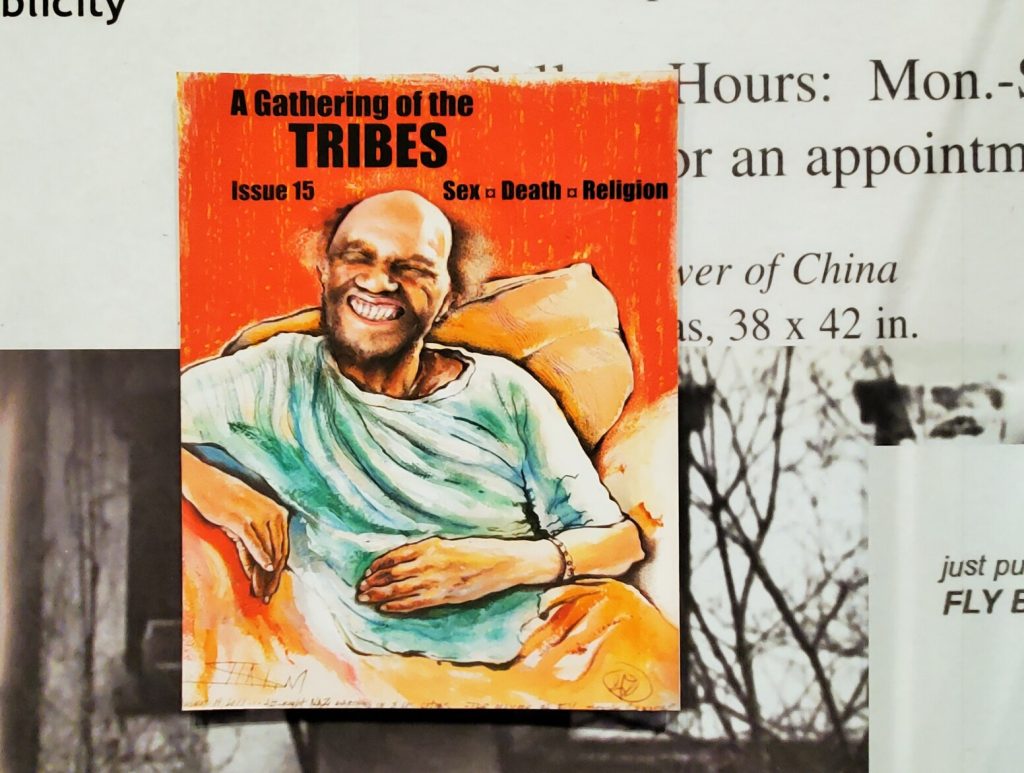

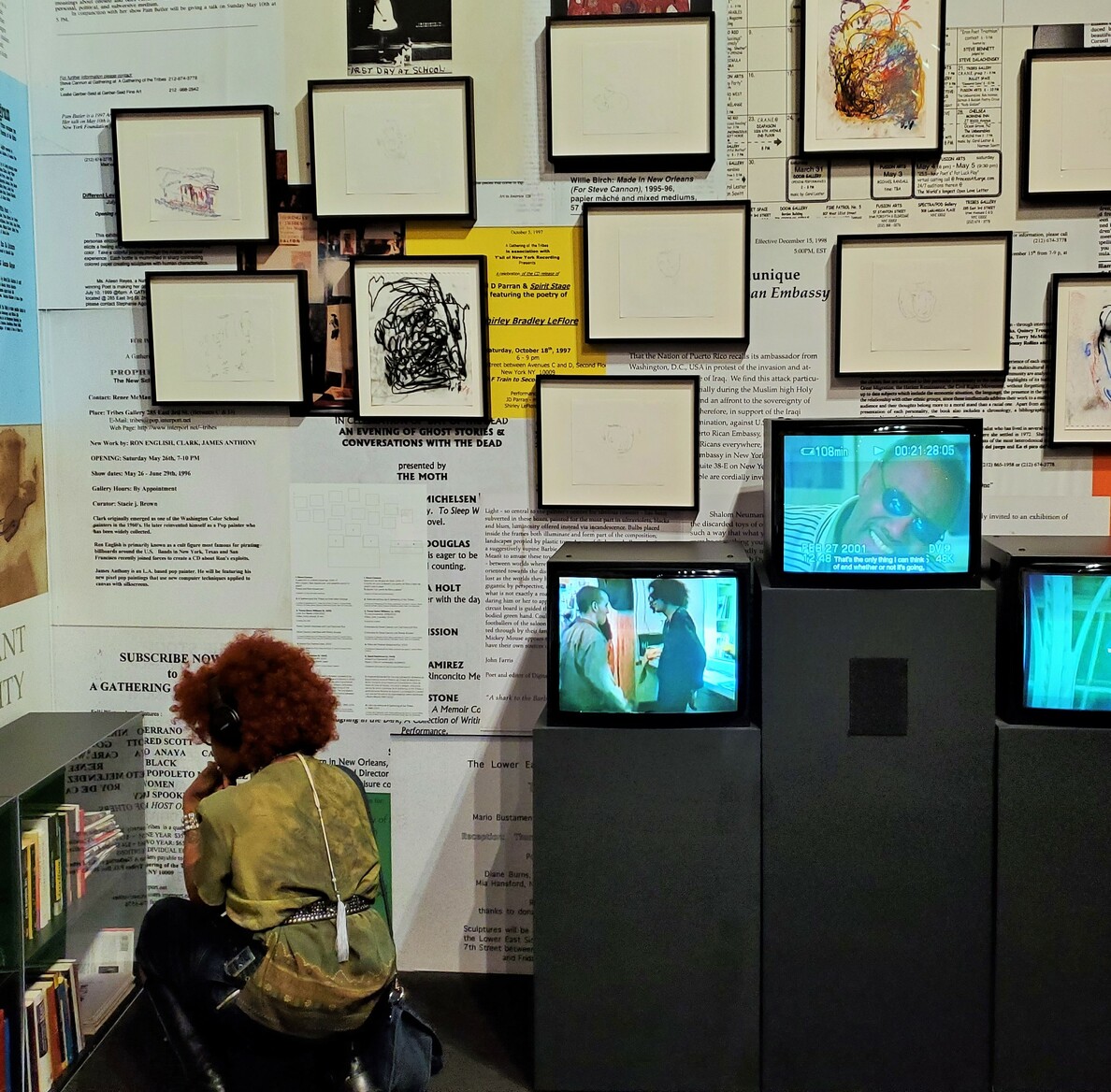

Of particular interest to those in the Downtown art scene, the Biennial also includes a recreation of the A Gathering of the Tribes art and literary salon space, which was located in the East Village. Tribes’ founder, the blind poet Steve Cannon, died in 2019. The museum, in fact, kicked off the Biennial with a two-day, marathon reading by the “Tribes community” poets.

The Whitney Biennial, which opens to great fanfare every two years and frequently finds itself the subject of controversy, often features pieces that veer into experimental territory in order to comment on the sociopolitical landscape of the time. By including a wide range of artistic forms and approaches, this year’s exhibit is particularly successful at holding up a discomforting mirror to our own moment, leaving the viewer shaken and moved.

The Whitney Biennial opened in April and runs through Sept. 5. The Whitney Museum of American Art, at 99 Gansevoort St., is open Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday from 10:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. and Friday from 10:30 a.m. to 10 p.m. For more information, visit whitney.org/exhibitions/2022-biennial.

Great that you are writing about Tribes and Steve Cannon and his/its presence at the Whitney Biennial! But just so you know, that last cover of Tribes that you show in the photo with Steve’s image was a satire! Steve was not bald before he died and his teeth were not so rotted and he did not look like a clown!

That cover was done before Steve tragically died in a nursing home after breaking his hip (a tragedy that didn’t have to happen because the nursing home was negligent). When that issue came out after his sudden and untimely death, it was a great shock to those of us who loved Steve, because of course our beloved poet and mentor that we loved so much, and who we cracked on, too, thanks to his mischievous ways, even in this case a rather gruesome satire (I don’t know, I’ve never been able to read the issue…) –our beloved Steve was gone!

Steve was a very handsome man even after losing his sight and becoming homebound. It would be nice if you could post an image that does justice to him and his great legacy.

Thank you!

Sarah Ferguson