BY DASHIELL ALLEN | Resident leaders of New York City Housing Authority developments citywide are raising the alarm about a bill currently in front of the state Legislature that they say would privatize their homes, effectively ending public housing as it’s currently known.

The Public Housing Preservation Trust Act would raise funds to complete desperately needed NYCHA repairs across the five boroughs. Among its most fervent supporters are Mayor Eric Adams and Comptroller Brad Lander.

The proposal would create, as its name suggests, a nonprofit “preservation trust,” transferring entire housing developments out of their current federal Section 9 program into Section 8 project-based vouchers supervised under private management, which would finance repairs. Additionally, this move would allow NYCHA “to borrow and loan funds and issue bonds,” to be paid back at a later date. The current bill, considered a pilot program, would include 60,000 apartment conversions.

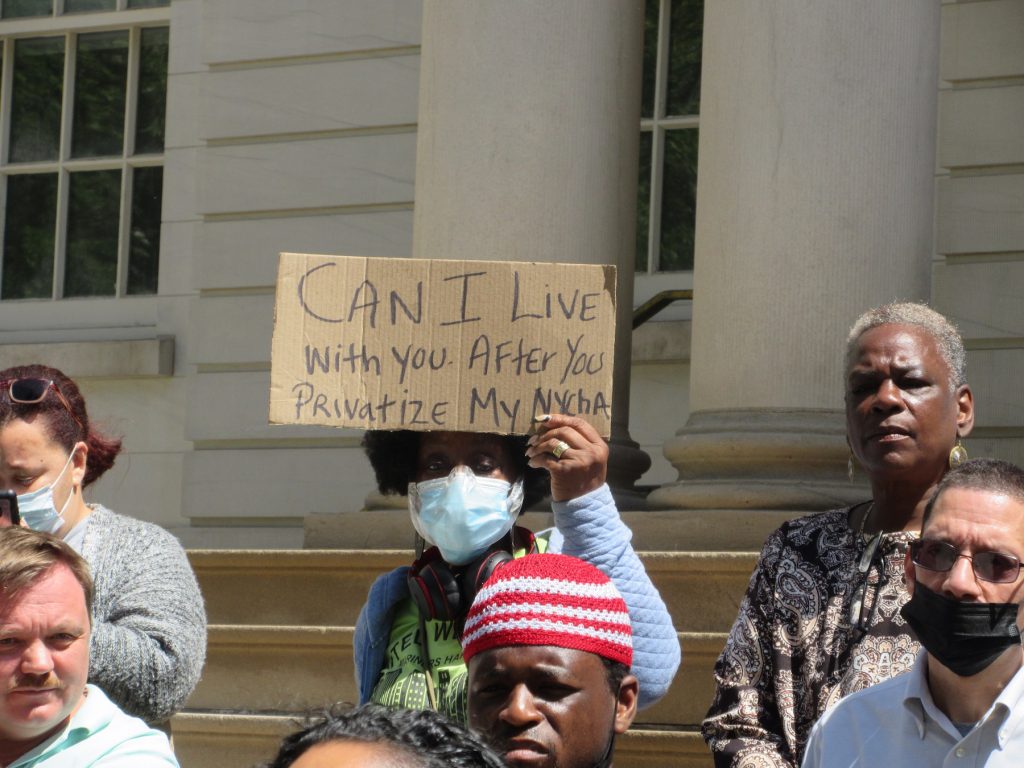

On Mon., May 23, several dozen NYCHA residents and advocates rallied on the steps of City Hall to fight against the Preservation Trust Act, which they view as a privatization scheme. The rally was held before the City Council’s executive budget hearings on public housing.

“People over profit!” “NYCHA lives matter!” they chanted. “Fund NYCHA now!”

“We are human beings. We have families. We have paid our dues. And God knows that we will be homeless if this trust goes through, because that’s what they’re doing,” said Aixa Torres, the tenant association president of the Alfred E. Smith Houses, located next to the Brooklyn Bridge. Torres charged that NYCHA residents were shut out of the bill’s conception.

She was joined by Danette Chavis, T.A. president of LaGuardia Houses in the Two Bridges neighborhood, as well as Councilmembers Christopher Marte and Alexa Aviles, the latter who chairs the City Council Committee on Public Housing.

“We know that NYCHA cannot be trusted to handle finances. We know that NYCHA cannot be trusted to tell the truth, which is why we oppose the public trust and also RAD,” Chavis said.

“I also wish there would be some compensation for current residents living in dilapidated conditions today, where people have died as a result of negligence and mismanagement,” she added.

The Rental Assistance Demonstration, program, known as RAD, is an Obama-era Department of Housing and Urban Development program, similar in many ways to the trust proposal. RAD also transfers ownership of affected public housing complexes into the Section 8 voucher program, while allowing housing agencies like NYCHA to “leverage public and private debt and equity in order to reinvest in the public housing stock.”

Once again, the privately raised funds are supposed to be used to make repairs and building upgrades. In New York City, RAD was rebranded PACT (Permanent Affordability Commitment Together). RAD conversions have been carried out in thousands of apartments across the city since 2016.

This January, a Human Rights Watch study found that two of six NYCHA developments converted under RAD saw increased eviction rates. Notably, Ocean Bay Houses in Far Rockaway saw 50 evictions after the shift to private management, resulting in a 1.4 percent eviction rate in 2017, and 1.1 percent in 2018 and ’19 — more than double the citywide average of 0.5 percent.

Recently, NYCHA has touted the completion of repairs at nine complexes in Brooklyn, dubbed the “Brooklyn bundle,” as a testament to the program’s success. Human Rights Watch’s report found, however, that many tenants’ perception of how repairs were handled remained unchanged after the conversion process. A 2021 investigation by THE CITY also found that several private contractors under the RAD program “botched renovations.”

Residents fear that the Preservation Trust is nothing more than a repackaging of RAD. Simply put, they want NYCHA to be fully funded in its current form, without converting it to another program.

“I don’t think it’s going to succeed,” said Chavis of the Preservation Trust. “In NYCHA I feel they’ve totally abandoned these residents because their total focus is on privatizing, on getting developers to redevelop it. So I don’t believe whatever money they even have that they’re sincerely applying toward rebuilding or refining anything.”

“In 2016 I stood here calling for $2 billion to fund NYCHA,” said Saundrea Coleman, a resident of Holmes-Isaacs Houses on the Upper East Side. “Now we’re at $40 billion: Understand the picture. They have disinvested in us. Why? Because it’s Black and brown people, the majority of us living in public housing. If the white flight didn’t exist it wouldn’t be a problem.” (Back in 2011 it was estimated that NYCHA needed just $17 billion in capital funding.)

“I never understand why the city and state always wants to invest billions of dollars in new programs when they can’t fix and fund the programs that are working today, like public housing,” Marte added.

Josh Barnette, a union representative with Local 375 DC37 and a full-time NYCHA employee, blasted breaks that are doled out to private developers.

“Every time we come here, just from the steps, we can see one more luxury tower that has apartments that we could never dream of living in,” he said. “That was built with public subsidy. There’s always money for that, but there’s no money for housing as a human right.”

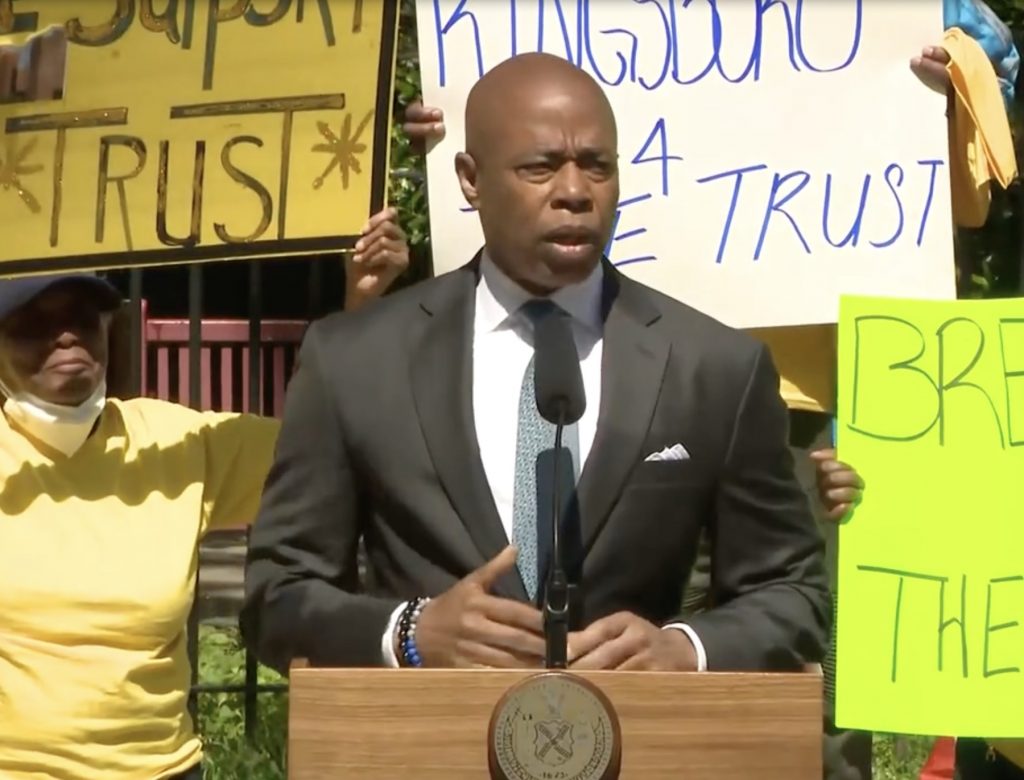

As the City Hall protest occurred, Mayor Adams simultaneously held a rally of his own in support of the Preservation Trust at the Polo Grounds Houses in Washington Heights.

“Trust the trust!” his supporters chanted.

“I’m very optimistic that the Public Housing Trust is an opportunity to create a new start, or shall I say a new change in New York City housing,” Barbara McFadden, T.A. president of the Sheepshead Bay Nostrand Houses, said at Adams’s rally. “I came far, and I’m not leaving without that bill.”

Comptroller Brad Lander, who introduced himself as a “housing nerd,” agreed.

“I sure understand why NYCHA residents don’t have a lot of trust,” he said. Still, he added, “This keeps public housing public, it preserves tenant rights, and it is the most significant legislation I have ever seen for giving resident leadership and resident involvement in choice and decision-making in the future.”

Lander was also joined by Jessica Katz, the city’s chief housing officer, and Adriene Holder, chief attorney at the Legal Aid Society.

One of the key benefits of the Trust legislation, Lander noted, is that it would codify tenants’ rights. Unlike other Section 8 residents, who normally pay 40 percent of their income towardd rent, NYCHA residents would continue to pay 30 percent, and would enjoy the same rights to organize tenant associations.

“There are many rivers that feed the dysfunctionality we have in our cities,” Adams said. “We need to dam each one, but this time we have a real stream of resources that can come through with the Trust.”

Adams also praised the Trust for giving the residents of individual developments the option to opt in or out.

For his part, NYCHA Chairperson Greg Russ dismissed the idea that the Trust is privatization as “propaganda” at the Council’s budget hearings.

“Unless we raise $40 billion, we are not going to be able to sustain the buildings. It’s that simple,” he warned. (Russ has been criticized in the past for overseeing RAD conversions in other cities, such as Minneapolis.)

Downtown Assemblymembers Harvey Epstein and Yuh-Line Niou are among just four members of the Assembly Housing Committee that voted against the Trust last week.

In a recent interview, Epstein explained to The Village Sun that the option to opt in or out of the Preservation Trust was unclear at best.

“The voting mechanisms around that are really unclear,” he said. “It just says, ‘NYCHA will create regulations on voting,’ which is not really appropriate. Why is NYCHA creating regulations on voting, instead of letting the legislation say anyone who’s a lawful tenant or a lawful occupant has the right to vote?

“There’s nothing that says how many people need to vote, so you could have a 1,000-unit complex and 50 people vote and if 26 of those 50 vote yes, are you saying that those 1,000 units are now part of the Trust?”

Epstein said in the future he would like to see a fully resident-controlled model for NYCHA, “like we do in community land trusts.”

More than anything, however, Epstein said he was listening to his constituents when he cast his vote.

“I represent 13 NYCHA developments and so I met with my leaders, and they all told me to vote against it,” he said. “Why are we not listening to the people who have been in power to lead our public housing developments? The decades of experience they have should be meaningful and impactful to all of us.”

Despite assurances that their rights would be protected after Section 8 conversions, residents could still be left in a precarious position, given that their federally protected rights would be codified only through state law.

“I think it’s a legitimate concern because you can change the statute now and you can change it later,” Epstein said.

Ramona Ferreyra agrees. A longtime resident of the Mitchel Houses in the South Bronx, she is the founder of the grassroots organization Save Section 9.

“If you can’t take out asbestos and lead from my home, what makes somebody think that NYCHA’s gonna sit there and support the existence of tenant associations?” she told The Village Sun. “Because it’s no longer a federal right. If they were to truly leave us in Section 9 we could sue them for those rights.”

Among the rights Ferreyra is most concerned about losing are job training, the freedom to organize and the ability of residents to continue paying 30 percent of their income on rent.

At the same time, she said, “I’m not trying to save NYCHA. NYCHA to me is a complete failure, but that doesn’t mean that the policy is wrong. It just means that the authority and HUD are not fulfilling the congressional laws.” Instead, she said she wants “the Housing Authority that existed in 1967.”

Ferreyra is in the process of organizing a lobbying trip to Washington, D.C., in mid-June. She called the federal government disinvestment from public housing “a national problem.” That’s why she’s planning to unite residents from cities across the country, tentatively including Memphis, Minneapolis, Boston, Oakland, Chicago and more.

With Albany’s legislative session scheduled to end on June 2, it still remains unclear whether the Public Housing Preservation Trust Act has a chance of passing. Last year, a previous version of the same bill was shelved, just two weeks after it was introduced.

As to the bill’s chances, Epstein quipped, “There’s four days left in session, I have no idea. This is Albany, strange things happen every day.”

Be First to Comment