BY JOSHUA HARRIS | I always liked watching films. I grew up around them while working theater parking lots in West Los Angeles. And I certainly watched my share on television (albeit broken up by commercials).

But it wasn’t until I stepped into the (old) St. Marks Theatre that I truly began to love the cinema. St. Marks showcased a panoply of old and almost old classic films in an old rickety theater that was reminiscent of “Cinema Paradiso” American-style.

“Diva,” “The Philadelphia Story,” “Top Hat,” “Captains Courageous,” “Jules et Jim,” “The Grapes of Wrath” and on and on and on… . Three and four times per week, sitting alone, I watched great film after great film.

Each month the schedule of “new” films billeted inside the glass case outside the St. Marks became a studied hunt for the rare gem of an unseen title and an array of mental notes to ascertain what films were worth the repeat viewing. I had become a St. Marks hardcore.

The theater smelled as if sweating water pipes were slowly loosening their rain onto a variety of growth-friendly surfaces — a dustiness whetted by persistent dankness. The width of the theater did not proportionally match the much-too-small screening area — a constant reminder that the building was designed for other purposes. The veteran corps of regulars knew that choice seating was as much about finding a working, worn-velvet chair than about sight lines.

As the house lights closed their eyes and the 16-mm projector cranked into motion, the crisp, snapping hum of the machine’s shutter door sent its ghostly magic onto the silver screen.

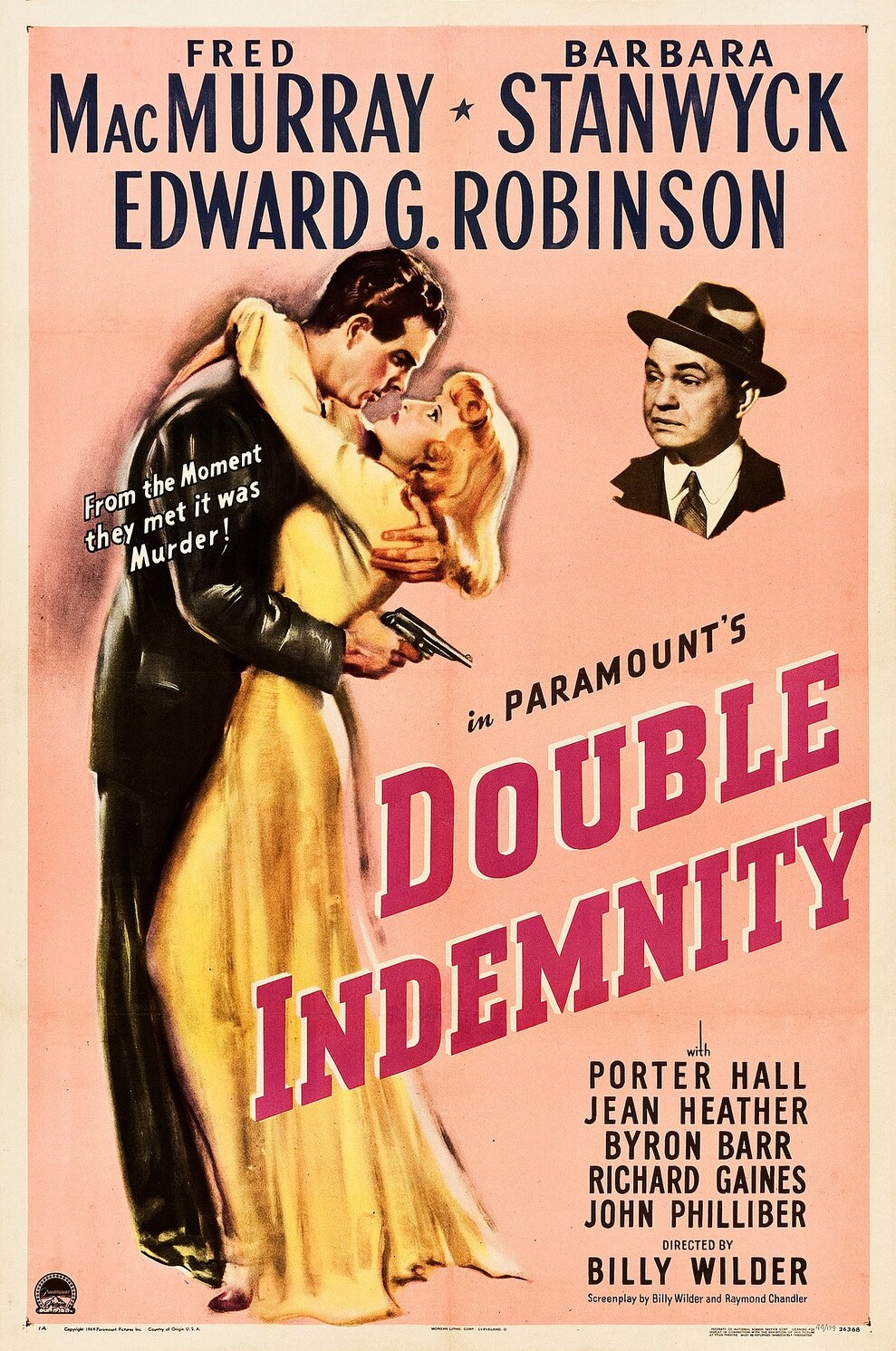

One solitary weeknight, practically alone in the theater, Edward G. Robinson, Fred McMurray and Barbara Stanwyck were performing “Double Indemnity” for probably my fourth time.

For a few moments, I left the world of the film and started thinking holistically about my present experience. My first revelation was that, in fact, every single one of the “characters” I was engaging with on the screen was, in fact, dead in real life. So then I thought to myself, “Well, if they are dead but are still living on the screen wouldn’t that really make them ghosts?” Stands to reason.

Then I thought to myself, “My personal culture is all about striving to leave a substantial record of myself either on television or film or radio or newspaper or home movies or Kodak snapshots or anywhere my presence can be recorded for posterity.”

Finally, I thought to myself, “In the realm of the ghosts — being recorded for posterity is a matter of life and death.”

Then I went back into the world of the film.

Harris is an Internet pioneer and the founder of Pseudo.com, a live audio and video Webcasting site founded in 1993. In the late 1990s, his Big Brother-like art project “Quiet: We Live in Public” (click here to watch trailer) followed every move of more than 100 volunteers — via 110 surveillance cameras — in a three-story loft at 600 Broadway in Soho. Harris formerly lived in the East Village at Fourth Street and Avenue A — as he put it, “above Sara Goodman’s (had a huge crush on her) Limbo coffee shop.”

In the late ’60s I would come into “the City” from Queens to see old Charlie Chan and Sherlock Holmes movies (I was obsessed with both) at the theater. Even then the theater seemed old and funky and I loved every thing about it! It was one of the reasons I knew I had to move into Manhattan as soon as I could. And I did.

This is so very sad. Another nail in the coffin of the East Village.

Heartbreaking to think of the theater being disappeared, potentially replaced by an unaffordable, soulless glass tower. It’s a family-managed business and building with deep cultural roots in the community. And the family is an active, positive contributing member of the community. The thought of losing this landmark is deeply painful.

Well stated, Joshua. I have similar memories of attending screenings there during my high school years in the 1970s. The theater is a one-of-a-kind, historic gem and it will be a true travesty if owners Lorcan and Genie Otway are evicted in the interests of lenders who are eager to get the building, which might well be torn down — much to the detriment of the neighborhood.

$