BY KAREN KRAMER | The first sentence we hear from Steve Post in the new documentary about his life and influence gives the viewer a window into Post’s quirky view on all things important:

“I want to talk about a subject that is near and dear to my heart: death. It’s a good subject in the fact that it’s universal as far as we know.”

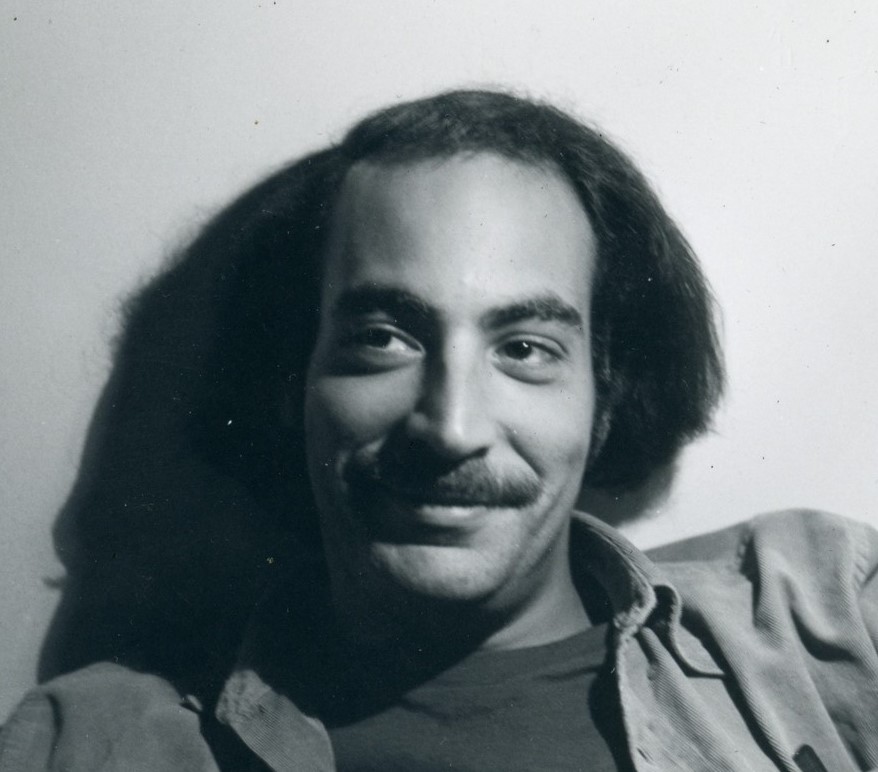

For those who knew the iconic radio personality, they remember him as a warm, cranky, opinionated, slightly neurotic curmudgeon who helped define FM radio. For those who never met Steve Post personally or heard him on one of his live radio shows, they won’t be able to forget him after seeing Rosemarie Reed’s new film, “Playing in the FM Band: The Steve Post Story.”

Opening at Film Forum on March 11, the documentary tells the story of how a shy, overweight, nebbishy kid from the Bronx grew up to become someone who helped to solidify FM radio as an important part of New York City.

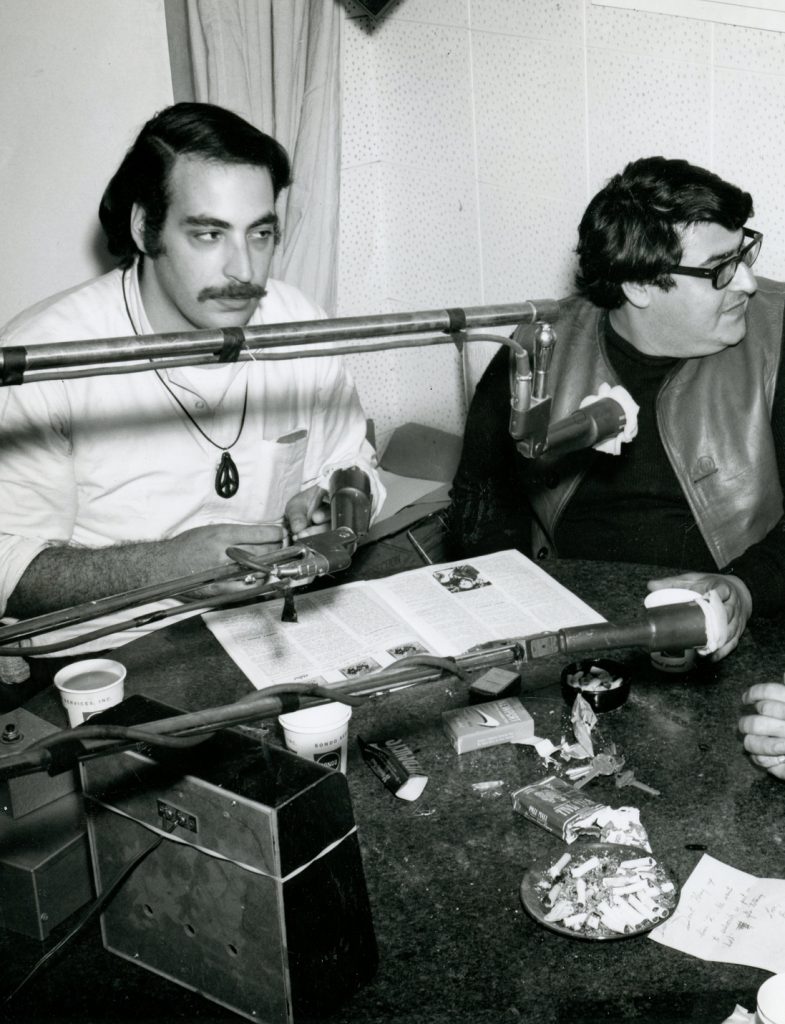

Before the creation of WBAI, FM radio had been a scripted and impersonal venue where the radio hosts adhered to the rules and rigid format that had been established. But within a short time WBAI FM changed all that.

“At the time we had AM, which was completely booked up and it was programmed second by second,” says director Reed. “FM comes in and it changes that. And WBAI and particularly Larry Josephson, Bob Fass and Steve Post brought freeform radio.”

What this new progressive medium wanted to do was create a different format…something freer and more personal. It strove to take on the issues of the day, especially the new emerging counterculture of the ’60s. It wanted the freedom from the constraints that more conventional radio required. Steve Post was the perfect conduit for this.

Post’s early years could read like a Dickens tragedy. His mother died of cancer when he was a child. Post and his older brother, Gerry, were sent to a boarding school where Steve, a sensitive, introverted child was constantly bullied because he was fat — something he remembered all his life. After spending two years at boarding school, Post went to DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx. He never did well in any of the schools he attended.

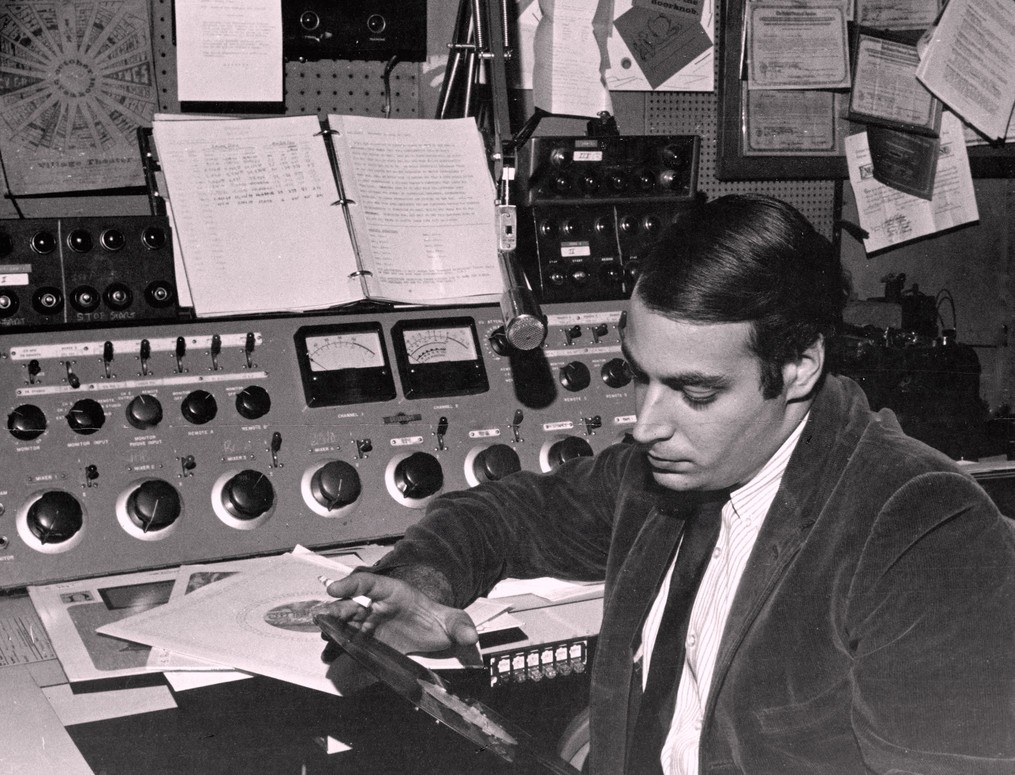

Back at home, Post found escape and solace in radio. At first he was just listening to radio, spending long hours in solitary passivity. Then his love of the medium turned into something more interactive. Ignoring admonitions from his father, the young boy surreptitiously took his dad’s Webcor reel-to-reel recorder and used it to make his own “programs.” He gave himself radio nicknames, such as Paige Turner and Luke Warm, and a lifelong calling was born.

“When I thought about the things that happened to me, it was always with a picture of the tape machine running,” Post says. “As I went about my daily drudgery, all experience was filtered through the part of me that had become Luke.”

In 1965 Post saw an ad that WBAI was looking for an editor for its program guide, “The Folio.” He went down to apply for the job, and although he was not placed in that position, WBAI hired him as the bookkeeper, something he knew he was completely unqualified for.

“I had been hired to be the bookkeeper despite the fact that I failed every single math course in my entire life, not to mention every other type of course” he says.

Fortunately, some of the station managers at WBAI recognized Post’s unique personality and resonant voice and intuited that he might make a strong on-air personality. For the next several years Post produced and hosted his first regular program, “The Outside,” in the weekend slot.

Post, a grumpy, sardonic contrarian, spoke about things that were not usually verbalized on radio — failed relationships, family life, personal flaws. He ranted against Chicken Delight and the absurdity of Jews for Jesus. He spoke openly about his childhood and bouts with recurring cancer. He spoke openly about sex. He even had a transsexual on the show, a topic that was barely spoken about 50 or 60 years ago. Listeners called in and asked intelligent questions.

“Steve would bring New York into the radio, into FM and it would be his observations of the world, good bad or ugly, warts and beauty as well,” says the filmmaker.

The show became a platform for many of the legends and events of the ’60s. Marshall Efron appeared on the program in the persona of an Indian swami named Rumpled Foreskin. But it wasn’t all jokes and lightweight banter. Post could switch quickly from humor to talking about the horrors of the Vietnam War.

The filmmaker’s portrayal of Steve Post becomes a window into much of what was going on in the ’60s and early ’70s with the counterculture and alternative institutions. We see footage of Abbie Hoffman and Paul Krassner, the publisher, editor and chief writer for The Realist. Civil rights leaders like Julius Lester and Bayard Rustin had several programs devoted to them, the latter causing a teenage girl to write in thanking Post for letting her know about Rustin’s civil rights work when she had never heard about him before.

Post knew all the important progressive figures of the time and even worked for a while helping Lenny Bruce.

“Lenny Bruce needed someone who could type,” Reed says. “Steve was a great typist and when Lenny Bruce needed someone, Steve volunteered his services and he worked with Lenny. He learned a lot about the First Amendment from Lenny Bruce.”

Post had a way of evoking strong sentiment from his colleagues in media. Marc Fisher, the author of “Something in the Air,” said, “When Steve was on the radio, he presented himself in such a way that you got all that angst but you also got someone who, just through the command of his voice, could connect with you.”

Danny Goldberg, author of “The Last Chord,” remembers, “He had this ability to talk to a listener as if he were your close friend”

The late Bob Fass of WBAI’s “Radio Unnameable” show put it more bluntly.

“This guy is a whack,” he said. “He was born to be on the air.”

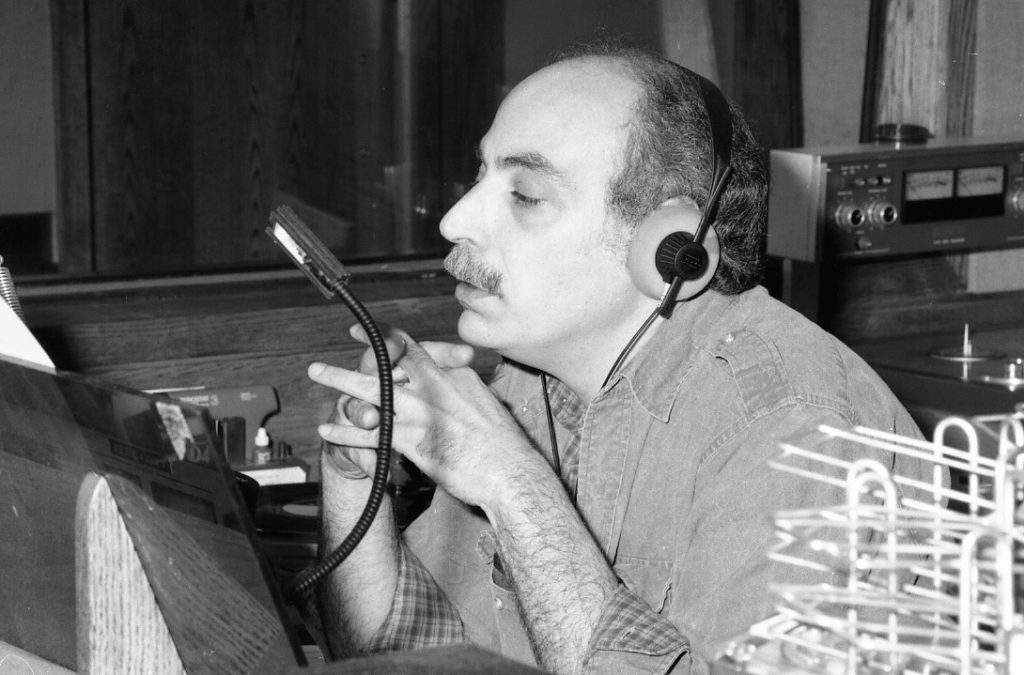

In 1981 Steve Post moved on to WNYC, which was — and still is — New York City’s National Public Radio station, where for 20 years he had the show called “Morning Music.”

His real contribution to the station was his ability to fundraise successfully on air. Once he threatened to keep the president of WNYC, Mary Perot Nichols, locked in the basement of the building until listeners gave enough money.

“He poured his heart out when we were buying the licenses from the city,” says Laura Walker, president and C.E.O. of New York Public Radio from 1995 to 2019. “Mayor Giuliani wanted to sell those licenses, both AM and FM, to the highest bidder and Steve was out there leading the charge. It was $20 million and Steve raised many of those dollars. It was Steve who said to Mayor Giuliani, ‘No, you can’t sell these to some commercial radio station. This is public radio and it’s for generations to come.’ And when he said that, people called in. And WNYC is here today in part because Steve made that plea and so many people answered.”

The film deftly weaves stories of Post’s personal life with issues that were going on at the time. There is also a skillful balance of mixing the serious with the comical.

One humorous story comes from Post’s memory of his father. As a single dad, who worked full time in his contracting business, the elder Post did the best he could for Steve and his brother. There is a hilarious — although poignant — scene in the film where the father comes home from a hard day at work to make meatloaf for dinner. The meatloaf is brought to the table and nobody understands why the food has turned out green. Somehow, the contents of a can of Comet had fallen into the chopped meat the father was molding into the loaf. They all felt fortunate that it was the brand, Comet, and not some other colorless cleanser, so that they were forewarned when their supper was presented with a green hue.

Filmmaker Reed is very adept at bringing these scenes together through animation. One of the funniest moments in the picture takes place when Post accidentally gets locked out of the radio booth while a piece of music is playing. He had been sitting at his desk before the microphone, on air, when he realized that a bathroom run was an immediate necessity. He put on a long-playing piece of classical music — by the 18th-century composer Jean-Philippe Rameau — and, believing he would have enough time to rush to the men’s bathroom down the hall and get back before the piece ended, he made a dash for the facility. But once inside, the doorknob came off in his hand and he found himself locked in.

Ever the professional, Post knew that he could not allow dead air time to occur when the music ended and that he had to get back to his desk immediately. The climactic ending to this scene should not be revealed ahead of time and one has to see the film to enjoy the outcome.

“There are no visuals on that at all and I had to build a story,” the filmmaker explains. “So the only thing I could do was go to animation and I animated the story based on his words. It’s important in a film when something is visual and those visuals don’t exist anymore or never existed, that we can go to something like animation and can fill in the gap and not throw away a story like that. It was my way of finding a way to get that story and it was such a great story.”

There are many other creative cinematic techniques that are used throughout the film. One of them is the use of a black backdrop behind every interviewee, rather than the standard home or office setting. Not only does this give a stronger presence to each of the people interviewed but it creates a visual continuity that weaves throughout the film.

“It’s a style that I’ve used a lot,” Reed says. “I generally don’t shoot in people’s homes. When the black background appears, it tells the viewer that an interview is happening. It sets it apart from the different elements.”

Reed peppers the film with “Post Principles” — bits of wisdom by Post that she writes in italics on what is meant to look like soft parchment and filmed against a black background. A typical “Post Principle”: “Life is a Gift. There are just lots of strings attached.”

Making the most of the cinematic medium, Reed uses strong visuals, still photographs, animation, archival footage and a superb soundtrack by the composer David Amram, thereby taking a simple narrative and elevating it to an artful documentary.

Reed, who has been a Tribeca resident for more than three decades, also worked at WBAI for a while and that is where she met Steve Post. As much as she loves FM radio, she is philosophic about the role that FM radio plays today, as opposed to how it was in the ’60s and ’70s.

“It may not be important today with all the podcasts and everything else,” she offers. “WBAI and every other station can be heard on the Internet. WBAI only reaches the tristate area. Whereas with the Internet, I could be in Paris, turn on the Internet and I could get WBAI in Paris. The new technology has brought whatever is on the FM band nationally and internationally, so FM today may even be less important than the Internet.”

However, like Post, she realizes what an important role FM radio played in shaping our culture.

Steve Post had a preoccupation with death — his death — and in keeping with that preoccupation, his goal was to have an obituary in The New York Times. When he died in August 2014 he posthumously got his wish. In the obituary The Times quoted Steve Post himself when it wrote, “The radio host with the world’s most biased newscast”

Kramer is an independent filmmaker and freelance writer.

Be First to Comment