BY THE VILLAGE SUN | Opponents of the city’s embattled plan to build a new borough-based “mega-jail” in Chinatown sued on Friday to quash the scheme.

Neighbors United Below Canal filed an Article 78 lawsuit that challenges Mayor Bill de Blasio’s proposal to construct a borough-based jail at 124-125 White St. The site is currently home to the two towers of the Manhattan Detention Complex a.k.a. The Tombs.

The group will hold a press conference announcing the suit on Tues., Feb. 18, at 2:30 p.m., at the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, at 62 Mott St.

The new project — which would take an estimated seven years to build — is part of the administration’s effort to close Rikers Island, shrink the city’s jail population and open new borough-based jails.

The lawsuit claims the new Chinatown jail would cause irreparable damage to indigenous land, historic landmarks, the financial stability of local businesses and the health of local seniors and residents. The litigation also charges the city has not adhered to New York State’s Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA), as well as the city’s Fair Share law and Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP).

“The work and outreach that’s gone into this lawsuit is work the city should have been doing in the first place,” said Jan Lee, of Neighbors United Below Canal. “It’s a robust case because we did meaningful outreach to our neighbors and came to realize just how deeply negligent the mayor’s plan was from the very beginning.”

The suit also charges the prison project neglects the Mohawks’ concept of Onkwehonwe-Neha — meaning the original people of the land and their lifeways — and flouts an early treaty between Native Americans and the Dutch.

“Erasure of our people and voices has always been a convenient strategy for the settler — also known as settler-colonial violence,” said Iakowi:he’ne’ Oakes, executive director of the American Indian Community House. “Without improved process, consideration and inclusion of Onkwehonwe, New York City would be in violation of its treaty obligations within the Two Row Wampum…covenant, remaining consistently aligned with…genocide of Onkwehonwe-Neha, the Original Peoples and our lifeways.”

The Two Row Wampum Treaty was a “separate but equal” agreement between the Five Nations of the Iroquois and the Dutch, under which each group basically would not interfere with the other.

A key site for Native Americans was Collect Pond — right in the middle of the Manhattan courts and jails complex, just southwest of the The Tombs — so failure to include Native Americans in the jail’s planning and review process “inflicts unique injuries on AICH’s members,” the suit argues.

Mintzer Mauch PLLC is representing the petitioners.

The case will include affidavits from industry experts that highlight what they say are the many environmental pollutants associated with this project and the direct impact these pollutants would have on people’s health. Affidavits also cover how the project would impact the urban design, shadows, landmarks and neighborhood character of one of the last surviving immigrant communities in Manhattan.

In addition to Neighbors United Below Canal and American Indian Community House, the plaintiffs include Chinatown activist Jan Lee; DCTV (Downtown Community Television Center), a community media center; Edward Cuccia, a local businessman; and Betty Lee, an area resident.

Betty Lee, 71, lives on Baxter St., right across from the proposed project, with her husband, who suffers from lung cancer.

Cuccia has real-estate and law offices in a low-rise commercial building at Walker St., around the corner from the project site. The suit notes his businesses would be negatively affected by the jail construction’s environmental impacts. And, in fact, the building’s ground-floor commercial spaces have already been impacted simply by the announcement that the jail project is in the works, the suit asserts.

What’s more, under a deal with the city, income from Cuccia’s and neighboring businesses provide “essential revenue” for 88 units of senior housing at Everlasting Pines, on Baxter St. A HUD Section 202 building with most residents in their 80s and 90s, Everlasting Pines has the highest concentration of seniors above age 100 of any such housing in the country.

Meanwhile, the commercial building also sports a daycare center and the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center on its top floors.

DCTV, at 87 Lafayette St., is half a block away from the project site and in a landmarked building.

The nonprofit American Indian Community House has its offices at 39 Eldridge St.

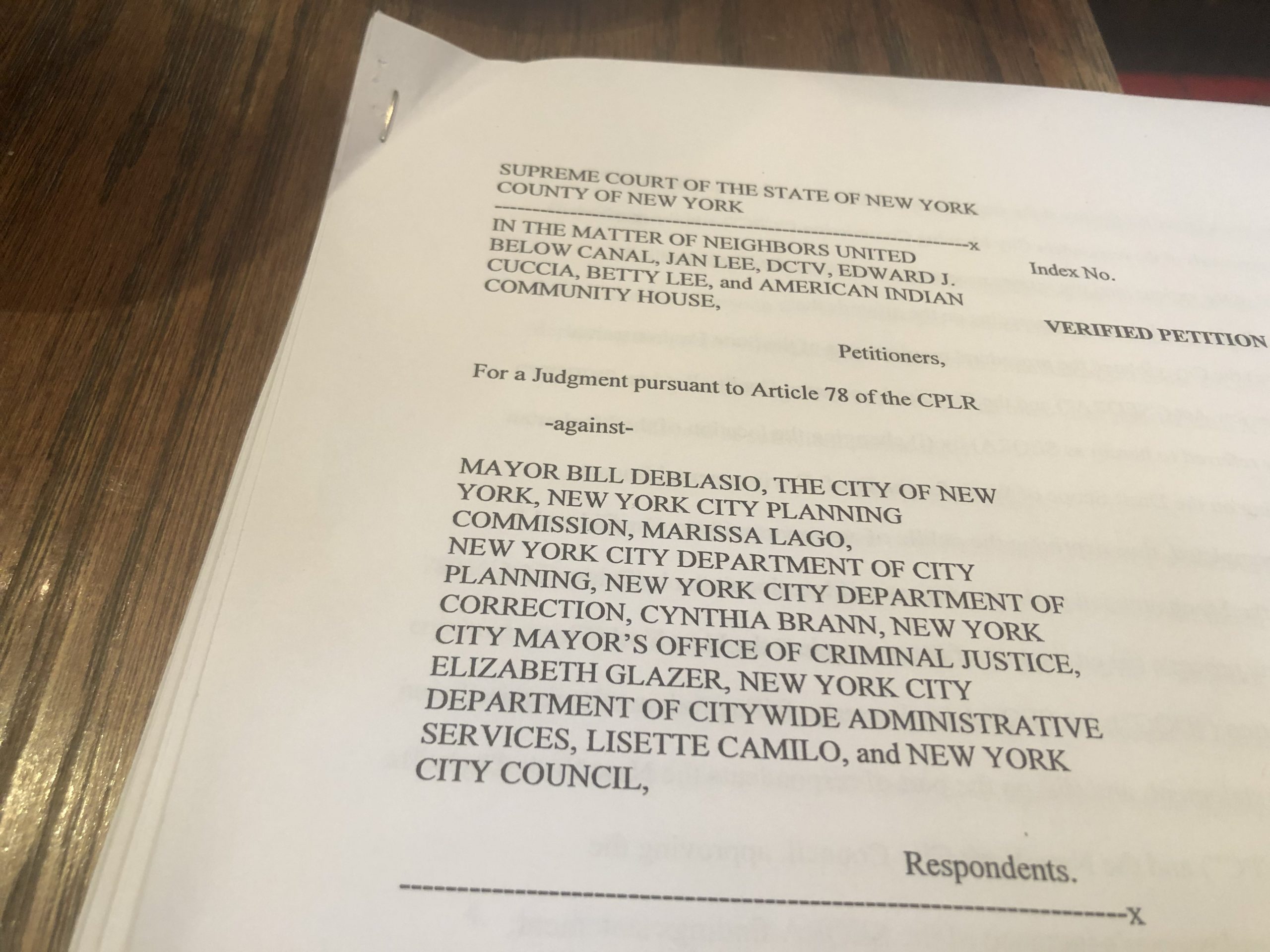

The suit is being lodged against the mayor, the City Planning Commission and Department of City Planning, the Department of Correction, the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, the Department of Citywide Services and the City Council, as well as the commissioners and directors of the various cited agencies and departments.

The suit argues that the city changed the location of the Lower Manhattan jail project — to three blocks north of the first proposed site — “after scoping on the Draft Scope of Work for the Draft Environmental Impact Statement was completed, thus depriving the public of an opportunity to comprehend, and comment on, the Manhattan jail project and its actual location at the beginning of the environmental review process.”

The new location — right next to senior housing, a daycare center and commercial businesses — “was even worse” than the first planned spot, at 80 Centre St., which is surrounded by government buildings, the suit notes.

Also, the plaintiffs assert, the Department of Correction and others violated SEQRA “by failing to adequately define the Manhattan jail project and identify and take a hard look at [its] potential significant impacts.”

Furthermore, the lawsuit charges, City Planning violated ULURP by lumping the Manhattan jail project together with similar jails to be built in Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx into one combined ULURP application and certifying it was complete, when it wasn’t, “making it impossible for the application to undergo meaningful public review in violation of the New York City Charter.”

In terms of the Native American complaint, the suit notes that, “Prior to European colonization, all of Lower Manhattan was home to Indigenous peoples, primarily members of the Lenape tribe, as well as many other tribes such as the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), who came to the area for its abundant natural gifts and the sharing of inter-tribal knowledge.”

Colonization resulted in “the systematic and violent taking of the land and the lives of Native Americans who called New York City home…” the suit states. Buildings were constructed on Native land — plus, Collect Pond, formerly located near the proposed jail site, was filled in. Collect Pond was a large, 60-foot-deep pool fed by an underground spring and used by Native Americans for drinking water.

“It was not just a water body or ‘resource,’” the suit notes, “but rather, like other life-sustaining elements of nature, was considered by Native Americans to be a relation, a vital family member around which Native American ceremonies occurred.”

However, by the early 19th century, Collect Pond had become a “communal open sewer.” By 1811, the city had filled in the pond, without regard for its significance to the culture of Native Americans and without their consent. Today, Collect Pond Park occupies some of the former site of Collect Pond.

The lawsuit also notes that Chinatown was hard hit by 9/11, including, on a health level, from the particulate matter in the air, as well as, on an economic level, from the impact on local businesses and the ongoing closure of Park Row for security reasons.

The suit cites Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, who conditioned her approval for the jail by saying, “The City bears a strong moral obligation to mitigate any further cultural and economic harm to the Chinatown community because of the permanent damage suffered by residents and businesses after 9/11: a 9% loss of population, while security measures reduced tourism by half, harming local businesses.”

Also, the plaintiffs assert, not all potentially affected groups were included in the six invitation-only Neighborhood Advisory Committee meetings for the jail. The N.A.C. members “were not representative of the community,” and, in fact, there were no elderly individuals among them, the suit charges.

Finally, much of the fresh food the Chinatown community lives on is bought at outdoor stands not indoor supermarkets. So, another negative impact of the jail’s lengthy construction, according to the suit, is that dust from demolition and construction would force Chinatown food vendors either to close their outdoor stands or dust “will wind up all over the fresh food.”

“It’s not just incompetent, it’s immoral to plan a jail without listening to industry experts, seniors who will be affected by construction, small business owners, nonprofits and Native Americans, whose ancestral remains may be underneath the site,” said Chris Marte, a Lower East Side Democratic state committeeman and a supporter of the lawsuit. “Every step of this process has been behind closed doors, and the few answers the community received only highlighted how dangerous and misguided these plans are. So we marched through the streets, organized our neighbors, and now we’re officially taking the city to court.”

The suit asks that the demolition of the current Department of Correction buildings at 124-125 White St. be blocked and that the city do a new supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the jail project, after a scoping session is held.

Be First to Comment