BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Opponents of the city’s drastic plan to bury East River Park and then rebuild it above the floodplain have filed a community lawsuit against the hotly debated project.

The suit was filed in State Supreme Court on Thursday by West Village attorney Arthur Schwartz. The plaintiffs include 16 organizations and nearly 90 individuals, many of whom attended the East Village press conference announcing the litigation.

The event kicked off with rousing remarks by performance-artist preacher Reverend Billy and Grammy Award-winning local Irish singer Susan McKeown crooning her “On the Bridge to Williamsburg.”

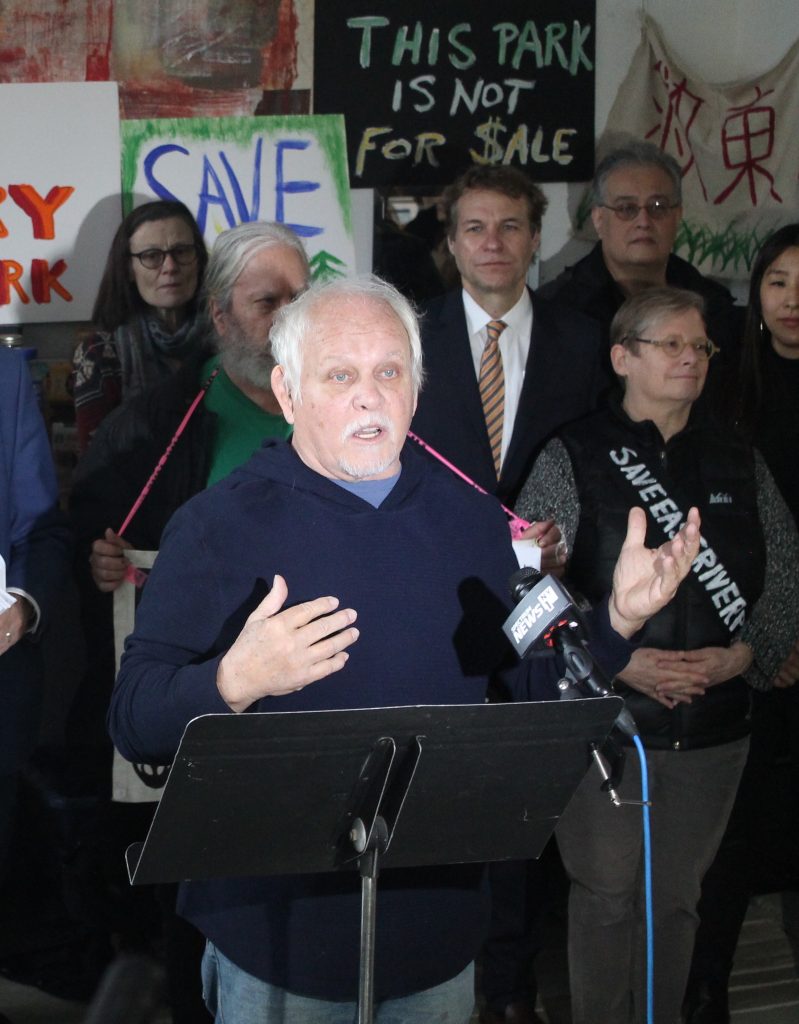

Attorney Schwartz then laid out the case. This is just the latest of his current slew of pro-bono community lawsuits: He’s also suing to stop the 14th St. busway; to put back removed bus stops on the M14 route on behalf of disabled advocates; and to block Mount Sinai’s plan to close the current Beth Israel Hospital and replace it with a mini-hospital.

“I’m the lawyer,” Schwartz said, “but I do litigation that I feel from the heart.”

Although he’s known for his activism in the West Village and on Hudson River Park, Schwartz noted he actually lived in the East Village for a time. His second wife was living at E. Sixth St. and Avenue D when they got engaged in the early 2000s and they lived there together for a few years while raising their young daughter.

“I have fond memories of my wife doing snow angels in East River Park,” he recalled, “and of my daughter going to the seal sculptures farther down and not knowing which seal was going to squirt water. So I appreciate the park.”

Voicing the concerns of everyone there, Schwartz said there’s no way the city could realistically complete its plan in five, much less 3.5, years — that is, to bury the 1.2-mile-long park under 775,000 cubic yards of landfill that would be 8 to 10 feet high, then build a whole new park on top of it.

More to the point, Schwartz charged that such a radical scheme would never fly in other, more affluent parts of Downtown Manhattan.

“It’s interesting to me, as someone who lived on Sixth and D next to public housing, that this is the community they chose to do this to,” he said.

In short, he continued, it’s hard to imagine the city trying to do the same thing to Hudson River Park. And, yet, he noted that during Superstorm Sandy, floodwaters on the West Side reached to Hudson St. in some parts of Downtown, and also inundated art galleries in west Chelsea.

“But they would never do this there or at Battery Park City,” he said, accusing the city of singling out the low- and moderate-income community for the disruptive project.

Also, Schwartz continued, the plan doesn’t even make sense, in that, just raising East River Park won’t stop water from pouring in from the north and south. The total project area is planned as 2.2 miles long, covering the park, which runs from Montgomery St. to 12th St., plus the esplanade to the north extending to 25th St. — but only the 58-acre East River Park would be physically raised.

“What about the water that will come in on either side of that?” he asked of the park. “The water won’t find its way in? That’s absurd.”

Schwartz noted that even when the City Council approved the plan, known as the East Side Coastal Resiliency project, Speaker Corey Johnson conceded it was “flawed.”

“When government acts on a flawed plan, we have a big problem,” the attorney warned.

Getting deeper into the case law, he said the concept of park “alienation” — that the state Legislature must vote “when there’s a substantial intrusion on parkland” or when a park will have a new use — was first codified in a case, Williams v Gallatin, in 1920. In that instance, the city tried to lease Central Park’s Arsenal building to the Safety Institute of America.

Then, about 20 years ago, the issue came up again when the city wanted to build a water-filtration plant in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx, Schwartz noted.

“It’s not just a concept,” he explained, “when the government wants to take parkland for another purpose that’s not a park purpose — like make a seawall.”

Specifically, the lawsuit states: “Using East River Park as the staging ground for building a seawall and taking away scores of acres from the public during that process, is a non-park purpose. And recreating a park on top of a seawall is sugar-coating a non-park purpose. NYC needs to be reminded of the law once again.”

The city lost both the 1920 case and the Van Cortlandt case.

Schwartz added that Assemblymember Harvey Epstein and state Senator Brad Hoylman, whose districts include East River Park, both correctly warned that the Legislature first needed to vote on whether to alienate the park before the city could move ahead with the project.

“It’s not even a close question,” he added.

The de Blasio administration, in an effort to address community concerns, agreed to phase the construction, so that at least 40 percent of the park would remain open at any one time. But the alienation vote still is needed first, the plaintiffs argue.

In addition, the lawsuit seeks to render “null and void” the City Council’s vote this past November approving the project. The vote was unanimous, with one abstention.

“This is a city that is supposed to be run in the interests of the citizens,” Schwartz stressed, though noting that the city violates this principle “again and again and again.”

He added that it’s not clear if any state lawmaker would even want to propose an alienation bill for East River Park at this point.

The lawsuit will be heard in February. Schwartz will ask the court to stop anything from moving forward on the project and also require the city to go to the Legislature first for an alienation vote before any contracts are awarded — “not even $1” — for the project.

The West Village attorney made a point of recalling how he took flak from Transportation Alternatives last year for his lawsuit against the 14th St. busway. In August, the transit-and-cycling activists angrily protested outside his townhouse, accusing him and his fellow busway opponents of being wealthy and uncaring toward low-income people’s transit needs.

“The last case, I was accused of bringing for a bunch of wealthy people,” Schwartz noted, adding, “This is not a bunch of rich people behind me. They don’t want a park in the sky.”

(Schwartz later pointed out that before the City Council’s vote to O.K. the project, Transportation Alternatives members publicly protested against the idea of losing the park’s bike path during the construction. So, while the group would seem a natural to join the lawsuit, they probably didn’t because he was the attorney, he figured.)

Charles Krezell, president of LUNGS (Loisaida United Neighborhood Gardens), who organized the press conference and is also a plaintiff, concurred with Schwartz about those bringing the suit.

“We are not very rich in terms of a community,” he said. “But we are very rich in terms of the love in this room.”

Fannie Ip, another plaintiff, spoke to environmental concerns about the project.

“We want soil testing before they break ground,” she said. “We need to know where the soil is coming from.”

Air-quality testing during the construction would also be needed, she added.

“What’s going to happen to the migration route?” she said of how bulldozing the park would impact the birds. “There was a bald eagle in [Riverside Park]. Are they going to come back?”

Ip said community members followed all the steps outlined by the city, in terms of attending outreach meetings for the project, submitting testimony and more.

“We’ve been playing by the rules the whole time,” she said, “and now it’s time for the city to do the same.”

The lawsuit notes that, “The proposed plan…requires the removal of 991 trees from the Park as well as the destruction of other plant life and flowers…including echinacea, bluebells and milkweed, which attracts monarch butterflies. As a mitigation, the City says it will plant 1,815 new trees as part of the landscape redesign.”

Another plaintiff, Amy Berkov, did a five-month survey of wildlife in East River Park.

Her research found that more than 440 species use the park, including 11 or 12 that are on New York State’s rare-animals list. The peregrine falcon is considered endangered in New York State, while the golden northern bumble bee and blackpoll warbler are threatened globally.

Berkov said she sent the findings to the city’s Office of Management and Budget and the state’s Department of Parks and Recreation, and had some e-mail correspondence back and forth with them, but only got “an enraged response that East River Park is just like a garbage park.”

To Berkov, like the other plaintiffs, the idea of completely burying the riverfront greensward under a new layer of soil, destroying its entire natural habitat, is horrific.

“I could not think,” she said, “of another city doing a project where they kill everything along two miles of shoreline.”

Also among the plaintiffs was David Eisenbach, a former candidate for public advocate. Afterward, he took a shot at East Village Councilmember Carlina Rivera for championing the project, which is in her district.

“It’s a boondoggle,” he told The Village Sun. “It doesn’t happen without Carlina Rivera’s support.”

But Rivera says the park-lifting plan is critical for protecting the surrounding community from future flooding.

Has everyone forgotten that when the seawall was strengthened some several years ago, Con Edison moved all the GAS and STEAM lines to the side of the FDR Drive. What kind of impact will that have to the adjoining residents from Jackson St. up to 23rd St., if that infrastructure is buried under 10 additional feet under ground and future problems arise? Have we all also forgotten that the Amphitheater was renovated after 9/11, for the children of the fallen during Christmas, with some of the stone from the WTC?

Why not just install a mobile protector along the sea wall that can be raised say 10 feet when a storm is approaching and then lowered when it passes? Of course it would have to be very strong to keep the water from breaking the protector.