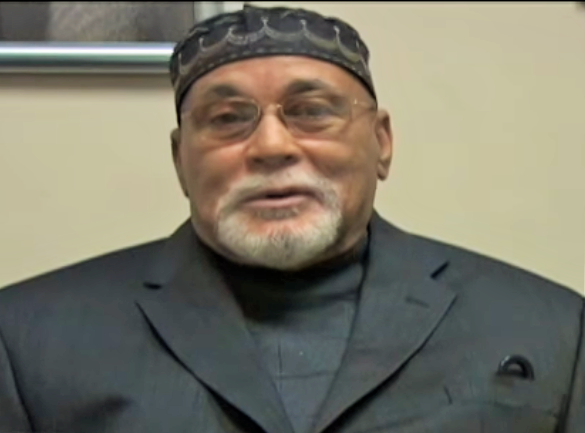

BY STEPHEN DiLAURO | It was the autumn of 1989 when I met Khalil Islam at Theater for the New City in the East Village. The occasions we met were during the Off-Broadway showcase run of my death row drama “Monster Time.” He was two years out of prison then.

Unjustly convicted for the murder of Malcolm X, Islam came to see the play thanks to David Rothenberg, founder of the Fortune Society, who was also a theater producer and publicist. The Fortune Society is a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping former prisoners transition into productive members of society. Rothenberg founded it after producing the Off-Broadway classic “Fortune and Men’s Eyes,” by ex-convict playwright John Herbert.

Rothenberg brought Islam to the theater and introduced him to me before the show. After seeing it the first time, I asked Islam what he thought.

“Can I come see it again?” he asked. “It’s what it’s like there. It’s real.”

That surprised me but I was happy someone liked the play that much. I told him to come as often as he liked. He saw the show another four or five times.

To me, “Monster Time” is anything but realism. It’s a three-character play about a condemned man on the night of his execution. He turns the tables and takes a guard as his hostage, makes him strip naked, and chains him to a rock at center stage, telling him that since this is Halloween night he is now costumed as Prometheus.

The condemned man is very damaged and lives in a world of hallucination. In fact, the third character, a wraith with an absurdist’s viewpoint, is one of his hallucinations. Likewise, the rock is how the convict sees a desk outside the execution chamber.

The production was a wild ride, with the director quitting a week before opening night, and two feuding, frustrated actors who were both siblings of Hollywood stars. Those two grew to hate each other and one of them walked out halfway through the run, to be replaced, improbably, by the unknown sibling of another well-known movie actor.

Though the play was a little less than 90 minutes, Howard Stern devoted three hours to talking about it on his show one morning. That was about the male nudity, though, not the immorality of state-sponsored execution.

To me, all the hoopla took away from the seriousness of the issue of the death penalty, which I still oppose. Instead, the production was becoming a carnival of feuding publicists and presumptuous brats, and their bourgeois white angst.

Over tea one evening after the performance, Islam and I talked about his reaction to the play. He told me I had captured something very basic about the incarceration experience.

“The strip searches without warning, the endless crazy people, that’s what it’s like,” he said. “That’s real.”

We talked a bit about my inspiration for the play — time I served for marijuana possession in a cell that once housed Bruno Hauptmann, the convicted kidnapper executed for the disappearance of Charles Lindbergh’s infant son.

“He was framed, too,” said Islam. I agreed.

It was then that we got around to his conviction for murdering Malcolm X. It’s a cliché that everyone in prison says they’re not guilty.

“We were framed by the police and F.B.I.,” he told me. Then he told me how Thomas Hagan (now Mujahid Abdul Halim) confessed to being one of the three shooters and telling the court that the other two defendants — Islam and Muhammad Aziz — had no part in the murder. (For the record, I was guilty of possessing marijuana and never denied it.)

The way Islam told it there was no doubt in my mind that he was innocent. When Islam spoke of his conviction and his time in prison, the sense of injustice was palpable in the air around us. I could sense that the man was wronged in a way that could never be made right.

Long before I met Islam, I was aware of the government’s war on Black activists, such as Bobby Seale’s treatment while on trial in Chicago; or Black Panther Fred Hampton being shot to death by the F.B.I. while he was asleep in his bed in that same city.

The facts are these: Khalil Islam, Muhammed Aziz and Mujahid Abdul Halim were convicted, under different names, of murdering the civil-rights activist and religious leader Malcolm X. The F.B.I. withheld evidence and covered up the fact that the shooters were informants paid by the agency. It is quite likely that J. Edgar Hoover ordered the hit.

It was an odd coming together: a young, white emerging playwright and a wrongfully convicted Black man. He loved my play, though, and that touched me in a profound way. He knew that I believed he was innocent. He said that made me a good man.

One of the actors in “Monster Time” used his connections to get Islam’s repeat visits to the show mentioned on Page Six, which referred to him as a murderer. David Rothenberg was furious at this, calling it betrayal and exploitation. Islam just stopped coming.

Khalil Islam did not say goodbye and we never connected again after he stopped coming to see “Monster Time.” I remember seeing his death notice in 2009 and wishing his soul peace.

I was not surprised upon learning that Khalil Islam and Muhammed Aziz had their murder convictions overturned this week. I was disgusted that it took so long (and allowed the real murderers and their F.B.I. enablers to escape justice). That it happened the same week Kyle Rittenhouse was freed after being tried for murdering Black Lives Matter activists is beyond irony, to be polite.

Whenever I’ve thought back to that production, it seemed that meeting Khalil Islam was probably the most auspicious event of the whole experience. It brought home that the so-called justice system is a lot different for Black men than for anyone else in the United States.

Remembering Khalil Islam in this context recalled other horrid and ongoing injustices: Mumia Abu-Jamal still rotting in prison for a conviction based on shady police evidence, and Leonard Peltier, the indigenous activist framed 38 years ago for the murders of two F.B.I. agents.

The exoneration of Khalil Islam and Muhammed Aziz came about thanks in large part to the Netflix-funded investigative documentary “Who Killed Malcolm X?” Maybe the streaming giant can fund like-minded projects and get Abu-Jamal and Peltier some justice before they die in prison.

If Netflix continues doing a better job than the cops and the courts, maybe more people will start to realize how thoroughly corrupt and racist the so-called justice system is. It’s long past time that white people do better.

DiLauro is a playwright. “Dinner with the Devil,” written during lockdown, is his most recent script.

Be First to Comment