BY DASHIELL ALLEN | A coalition of Lower Manhattan residents, with the support of most of their elected officials, is confident that building a 900-foot tower with 100 percent affordable units at 5 World Trade Center is possible — but only if the developers and state agencies involved will come to the table.

The Coalition for an Affordable W.T.C. Tower 5 is led by the 9/11 survivors that never left Lower Manhattan. For them, this fight is deeply personal.

After the tragic events of Sept. 11, 2001, 9/11 survivors and Lower Manhattan residents told the city that they needed to be included in the area’s recovery efforts. Their demand was clear — any new development at the World Trade Center should provide affordable housing, with a preference given to the community.

“We were told that the air was safe, that we should be going about our daily lives,” said Mariama James, a co-founder of the coalition.

Now, on the 20th anniversary of the attack on the Twin Towers, James has seen countless friends, neighbors and family members suffer from 9/11-related illnesses.

“I have friends and neighbors that are dying all the time,” she said. That includes her father, who recently passed away due to a 9/11-related cancer.

That’s why James wants 5 World Trade Center to be 100 percent affordable, and for preference to be given to 9/11 survivors and essential workers. She’s concerned that Lower Manhattan has become unaffordable for most, and that the children who grew up in the aftermath of the attack have “been priced out of their own neighborhood.”

Starting immediately after the attack the late Tom Goodkind demanded that Lower Manhattan’s recovery include affordable housing.

“He championed this cause and championed it on the community board,” remembers James, herself a Community Board 1 member. “The [C.B. 1] Affordable Housing Committee was Tom’s baby.”

Tom Goodkind died of a chronic illness in February 2019.

“This is an opportunity that we can’t miss for our community to have affordable housing,” Assemblymember Yuh-Line Niou said. “The possibility gives me goose bumps,” she added, “because if we don’t limit ourselves, we can come up with something really brilliant.”

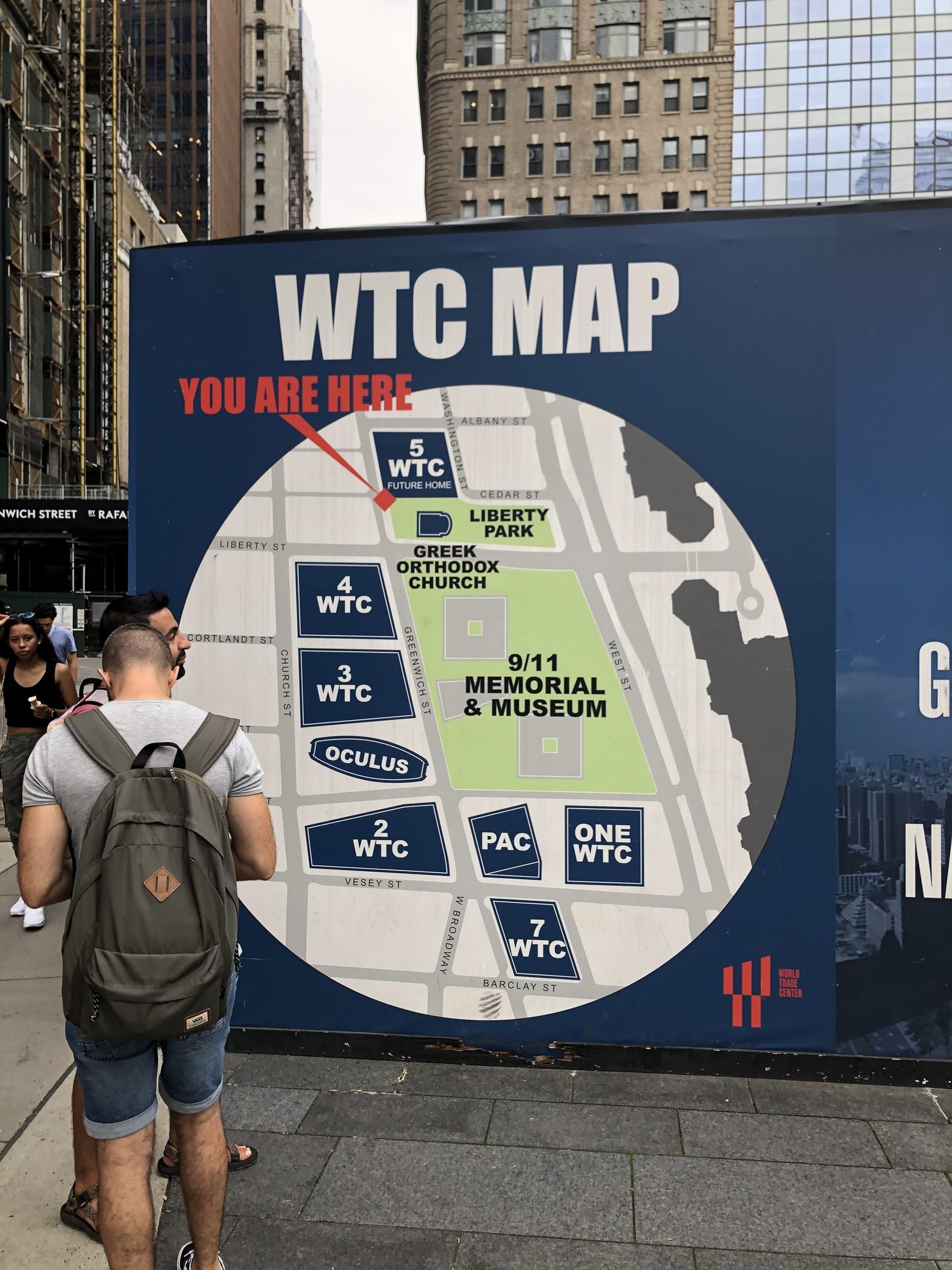

This past February the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, in a closed bidding process, selected a bid for 5 World Trade Center from Brookfield and Silverstein Properties. The mixed-use tower would contain 1,325 units, 25 percent of which (330 in total) would be permanently “affordable” for families making up to 50 percent of area median income (A.M.I.), presumably funded through Section 8 vouchers. Section 8 is a federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD) program that provides funding, distributed through local agencies, for either project-based or individual low- to middle-income housing.

But that’s not enough for the activists, who see no benefit in Lower Manhattan adding to its stock of market-rate luxury housing. They cite the L.M.D.C.’s original mission statement, which asks that “a significant amount of land area be devoted to housing” and that “this housing must be for a wide variety of income levels.”

“The L.M.D.C. has not created a single unit of affordable housing,” said Vittoria Fariello, a 9/11 survivor and Democratic district leader. “We can do better. We can definitely do better.”

The process to develop 5 World Trade Center, the previous site of a tower that housed Deutsche Bank, has been shrouded in secrecy and lacking transparency, according to Fariello, an attorney who previously investigated corruption in the city’s Department of Buildings.

The site was originally owned by the Port Authority, which swapped its administration with the L.M.D.C in 2006, in exchange for the future Performing Arts Center and 9/11 Memorial. Then in 2019 the two agencies began a private bidding process for the site, for which they claim to have received five proposals that could have been either commercial or residential.

The L.M.D.C., formed in 2004, is a subsidiary of the Empire State Development Corporation, “charged with assisting New York City in recovering from the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and ensuring that Lower Manhattan emerges as a strong and vibrant 21st-century central business district.”

Holly Leicht, the E.S.D. executive vice president of real estate development and planning, told C.B. 1 in May that because 5 World Trade Center is technically owned by the Port Authority, which isn’t authorized to develop residential projects, the L.M.D.C. needs to compensate the Port with 5 W.T.C. revenue equivalent to that of a commercial or office building.

“They’re saying things that only make sense within their own self-referential world,” said activist and historian Todd Fine, who doesn’t understand why one state agency needs to be compensated by another.

The bidding process and subsequent negotiations included input from a closed-door Community Advisory Committee, which, according to James and Fariello, failed to adequately include the voices of 9/11 survivors and Lower Manhattan residents.

“The fact that they have not been transparent tells me that they don’t want community input,” Fariello said. “But they must have it, you know. New York is not a playground for politicians and developers.”

On Aug. 10 Congressmember Jerry Nadler sent a letter to E.S.D. to request “the expansion of affordable housing in the proposed redevelopment,” and encouraged the agency to explore expanding Project-Based Section 8 to the project. On Aug. 31 Congressmember Carolyn Maloney wrote to Governor Kathy Hochul with a similar request.

Tensions between the developers and activists reached a boiling point at an Aug. 16 community board meeting when Leicht said that “the cost of construction unfortunately far exceeds the amount of state allocation for bond authority,” refuting Congressmember Nadler. “It would be entirely unprecedented for there to be vouchers available for this project,” she added.

However, James said, “When we want something to happen, we tend not to just take that there’s not enough money as an excuse.”

Richard Corman, a member of C.B. 1 and president of the Downtown Independent Democrats club, said that, even though the agencies were dismissive, “Holly Leicht and Empire State wouldn’t even discuss any of this until Nadler wrote his letter.”

“Now at least,” he said, “we’re having that debate that the administration basically wasn’t open to before, and that is progress in and of itself.”

Last week Assemblymember Niou and state Senator Brian Kavanagh, along with representatives from Nadler’s office and Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer’s office, met with the L.M.D.C., Port Authority and developers.

“I asked personally for numbers. I wanted to know the numbers for how much it costs” to develop the site, Niou told The Village Sun. “They were telling me that it’s much more costly to build a high-rise affordably. Having the numbers we at least [would] know what kind of programs and what kinds of dollars would be needed.

“Right now, as I’m seeing it,” Niou added, “there aren’t that many places where we can build affordable housing of this size and of this magnitude with this many units. And even if we were to spread the units all over New York, would we be able to build this many of this cost? I want to know the math.”

In addition to the project’s financials, the elected officials requested to see the other four bids submitted for the site, and to be given a clear time line for when the project could break ground. They have yet to receive any answers.

As far as Niou and the 5 W.T.C. coalition are concerned, modifying the building’s physical design to maximize both its affordability and profitability is not off the table either.

“If these are affordable housing units, we can reconfigure the whole thing and it could be more units. It’s not like we’re going to need a two-story penthouse,” said Niou, who also expressed her distaste for developments that separate residents based on their income level, often creating so-called “poor doors.”

As of now the community is open to exploring all options for funding the tower as 100 percent affordable. They are interested in state and city Section 8, or even starting a new type of program that would apply to the building.

“There’s L.M.D.C. funds, there’s FEMA dollars, there’s 9/11 dollars allocated for this site,” Niou noted. “There’s also Port Authority dollars allocated for this — there’s tax abatements, there’s [many things] that are this site only.

“If you’re negotiating with HUD you could just start a whole new program,” Niou said. This could, for example, combine the best parts of Mitchell-Lamas — middle-income complexes that are vulnerable to deregulation — and Article 4, a deeply affordable program that exists at the nearby Knickerbocker Houses on the Lower East Side.

Another idea worth considering, according to Todd Fine, is the Community Land Trust model, where residents of a building collectively own the land that it’s developed on.

Over the past 20 years Lower Manhattan residents have witnessed the deregulation of hundreds of units of affordable housing, making their case to reverse that trend even more urgent. Mariama James lives in Southbridge Towers, which was the last New York State-owned Mitchell Lama co-op that went private in 2014. Something similar happened at Gateway Plaza in Battery Park City in 2020: Of its original 1,700 rent-stabilized units, Fariello, who lives there, said that only around 300 remain.

The fight for a 100 percent affordable new tower at 5 World Trade Center is occurring simultaneously with the proposed Soho/Noho upzoning, and some activists see the two as interconnected.

“You can’t see any of these projects in a vacuum,” said Christopher Marte, the Democratic nominee for City Council District 1. “The people pushing for affordability at 5 World Trade Center are actively involved in Soho/Noho.” He noted that in the upzoning, “there’s no commitment to even build one affordable housing unit.”

Richard Corman said that D.I.D. would have pursued fighting against the Soho/Noho upzoning and fighting for affordability at 5 World Trade separately.

“But it just does for me reveal the false premise of these other major city initiatives,” he said, “when in fact we have this incredible opportunity for so much more affordable housing, that neither the city nor the state at this point, at least not yet, is jumping on.”

In her testimony (1:19:41) at the Sept. 2 Department of City Planning ULURP hearing on the Soho/Noho rezoning, Borough President Brewer mentioned 5 World Trade Center, along with 2 Howard St. — another site identified by the community — as alternatives to the Soho/Noho plan, in terms of increasing affordability. She indicated that she rejects the upzoning as it is currently written.

For the Coalition for An Affordable W.T.C. Tower 5, this isn’t any old housing battle. It’s deeply personal and, on the 20th anniversary of 9/11, historical.

“It’s my feeling,” Fine said, “that what is produced at the World Trade Center reflects what are the values of our society when we have a blank check to do anything.”

Be First to Comment