BY JOHN PIETARO | It took Brooklyn’s Roulette performance space to break COVID’s hold on Shelley Hirsch. Now it seems there’ll be no stopping her. Hirsch — vocal acrobat, poet, performance artist — was a new music original long before Downtown moved across the river to BK.

A founding member of avant rock band the Public Servants, Hirsch had worked her way through fringe arts circles in San Francisco and then Europe before returning to her native ground of NYC.

Arriving in time for the underground creative milieu’s coming of age, she began collaborating with Christian Marclay, John Zorn and Elliot Sharp, as well as assorted no wave artists.

“I wanted to use my voice the way Arto Lindsay did, utterly raw, but I couldn’t quite go that route,” she explained to this writer several years ago.

After crafting her own extended vocal concepts, Hirsch spent decades working within both new dramaturgy and free jazz on the edge. At this point her résumé reads like a list of some of the most vital avant gardists, including Butch Morris, Jin Hi Kim, Ned Rothenberg, Alvin Curran, Fred Frith and Ikue Mori, as well as the aforementioned Marclay, Zorn and Sharp. She’s played every major experimental arts festival, with multiple tours around the planet, but then there was this thing called the pandemic. And a damning silence.

On March 15, Hirsch was back onstage for the first time in too long. Roulette, which hosted her many past performances, broadcast it widely. The house was necessarily empty, the darkness ensued, but the Downtown magic persisted. “The Body Remembers,” a work comprising older and new pieces, seemed to confront her issues of this lockdown, both aesthetic and sociologic.

But Hirsch has long conceived of art grown from the body’s own memory. As she put it, “It’s our biggest recorder and our storage house.”

The performance began full throttle with her “Paper Piece,” from 1986, revealing the singer, seated amid shredded wrappings, cartons and newsprint, in the glimmer of a tight spotlight. Hirsch’s theatrical, aerial vocals painted the hollow theater with vocalizations encompassing her trademark affective shifts. Childlike, Hirsch upturned the torn sheets, hinting at words but speaking in splinters while expanding the circular construction of paper as the stage lights slowly widened.

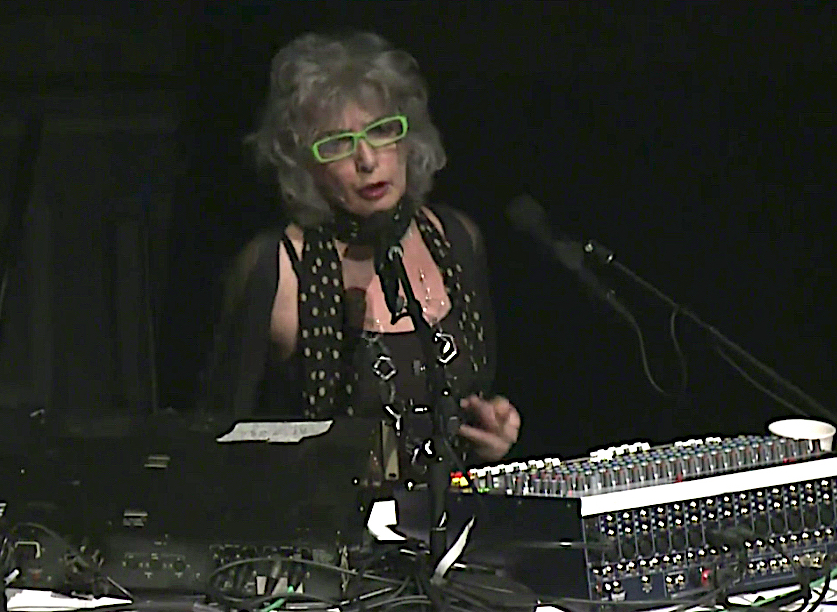

“Letting the Electronics Lead Me” had Hirsch seated at a black-draped table with an series of electronics feeding her voice through effects and delays. In a blunted sort of Sprechgesang, she pondered, “I was…I was lost…I was found,” an electronic harmonizer enhancing natural leaps over octaves.

She was next joined by sound artist Michael Schumacher, who wielded his own array of computer-controlled electronics, casting sounds about Hirsch’s operatic utterances and readings. As she’s been wont to do in recent years, Hirsch was writing real-time prose and poetry on large variously positioned pads and sheets, allowing the sounds, as well as her own frenetic movements, to inspire the words. Schumacher’s contrapuntal music often originated in what he captured directly from the singer, albeit, played back treated and in variously metered repetition.

The final piece was a duet with violist Joanna Mattrey, who played rich, dark accompaniment to Hirsch’s spoken prose. Again, Hirsch wrote in real time, this time at a laptop with the words projected on a large screen. The work was a meditation on the anniversary of New York’s lockdown last year.

As Mattrey’s haunting modal improvisation, so spare in its vibrato, resounded across the hall, Hirsch assured, viewers as much as herself, “We will touch again.” Throughout the performance, Roulette’s masterful videographers not only served to record the event, but actually became another aspect of the performance, fading and overlapping the imagery, moods and messages as Hirsch bent, swooned and emoted.

Be First to Comment