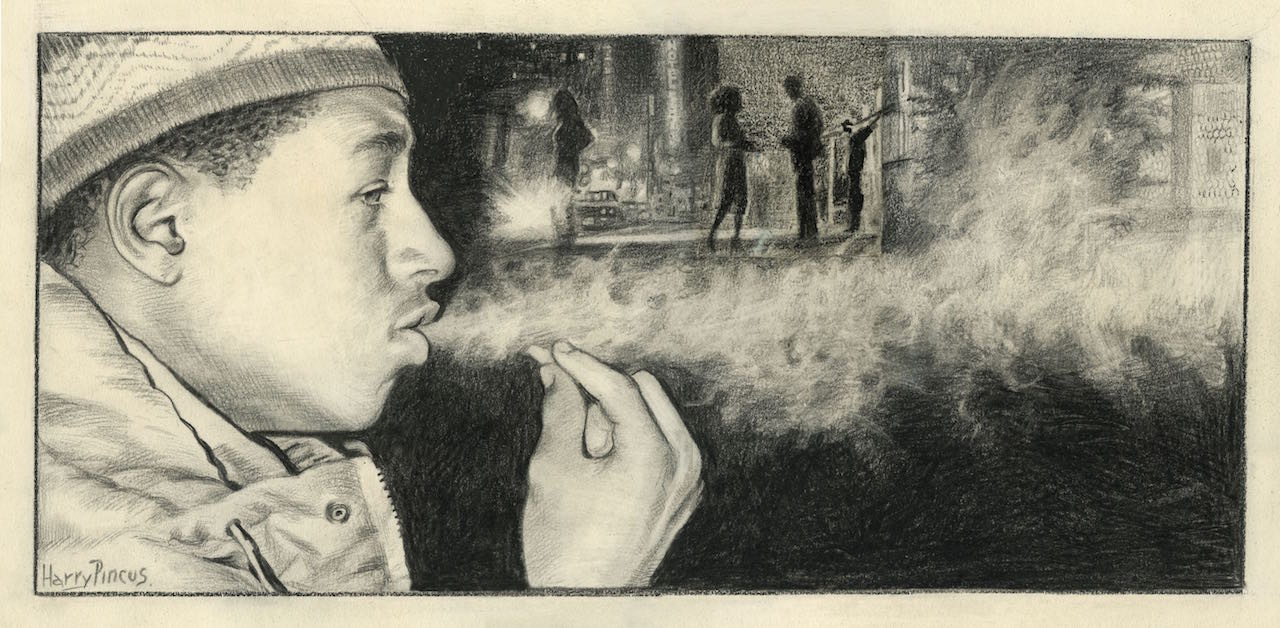

BY HARRY PINCUS | They say the world will not end with a bang, but with a whimper, and so the great day is cometh, and weed is now legal.

Legal for our suddenly open-minded Upstate legislators, with their empty pockets hanging out of their suits, and legal for the hucksters on the financial channel, who are already producing industrial weed on a gigantic scale, and selling their boutique dope on the stock exchange.

Legal, too, for those who unjustly spent years in prison under the racist and draconian drug laws put forth by the Rockefeller regime, which diverted people from treatment to incarceration. Those are the people who should benefit from this spiffy new form of commerce. Those are the people who should profit from this “revenue.”

It wasn’t long ago that a cop chased a teenaged kid into his own home, and shot him dead while he was cowering in his own bathroom! Not surprisingly, the young man was African American, and the cop claimed that he thought he was in possession of marijuana! Perhaps such a calamity will now be averted, and perhaps black kids won’t get hassled and arrested. But I worry that the sale and heavy promotion of marijuana at the corner bodega will mollify the very people who should be rising up.

Certainly, no one should go to prison for smoking pot, but I dread seeing ads for our sacred weed plastered around with the likes of gambling casinos and sports betting. For that matter, even in my hairiest daze as an all-night Bronx cab driver, I knew enough to avoid driving while high. So will I now be sharing that ribbon of highway which runs toward the great pot of gold in the sky with stoned neighbors?

It’s too bad that David Peel is not here to collect royalties for his “Have a Marijuana” song when it ends up in a commercial. I once saw him get into a fist fight with his conga player onstage at the old Gaslight, so he paid his dues.

And what of the pioneers who marched for legalization every year? Will my old friend Aron Kay, the Yippie Pie Man, get some security for his old age, if not the same medal that Trump presented to Rush Limbaugh? I once greeted Aron at The Cooper Union, only to find myself face to face with Jerry Brown, the governor of California, a few moments later, and the gov was wearing a face full of whipped cream.

We saw pot as a way to step out of our constricted, societal shoes and examine our lives from a different point of view. Some never found their shoes again, and many of the grizzled veterans who marched at the marijuana parade every year looked like they may have taken a costly, and permanent, detour.

I don’t mean to discount the damage that pot, and other drugs have done to people’s lives, and I’m particularly concerned about the space race to stronger and stronger “product.” There is a potential for great harm here, just as there is in criminalization.

I personally drifted away from the old communal ritual when I became a parent, many years ago. One day, as I was pushing my infant daughter in her stroller, a taxi cab slammed around the corner and almost hit her. At that moment, I realized my new mission, and my new mantra… “It’s not about me!” I suddenly understood why the wartime bombing of mothers and children was more tragic than the loss of a 28-year-old illustrator who had three parties to go to that weekend, and I realized in an instant that I would have thrown myself in front of the stroller to save my child.

From then on, getting high seemed antithetical to my mission as a parent, not to mention the timely requirements of my profession, as a deadline artist for newspapers.

But that’s just me, and I often wonder if my early years as a devoted imbiber weren’t crucial to my development as an artist. When I was 18, I went to visit my father in the cancer ward at the old Interfaith Hospital, on the way to an exhibit of Vincent Van Gogh paintings at the Brooklyn Museum. A friend met me there, with a little art deco cigarette case full of joints, and by the time we got to the museum, it looked like a great Greek temple, surrounded by white fluffy clouds on a hill.

I understood Van Gogh fully, and for the first time, on that day, just as I got to know Rembrandt’s etchings in Amsterdam. I hardly expected a uniformed guard at the Rijksmuseum to hand me a box full of original, unframed etchings, and carefully place each piece on a viewing stand, but Rembrandt spoke to me that day, with his glowing black sun, just as the high from that hash cookie kicked in.

In those days, we traveled amongst friends, and weed was our sacrament. I’d gone to Amsterdam to find some grass or hash, which was largely unavailable in Paris, and when I arrived amongst the canals, a large and somewhat unsavory gentleman walked up to me and simply said “sheet.” This seemed good enough, and I soon found myself waiting in a brick cul-de-sac, as my new friend arrived with a tiny packet of tinfoil, and a huge knife. All things considered, I gladly accepted my purchase, and strode off toward a little bridge, where I passed a Dutch hippie in a green felt hat with a large feather. When I asked the living Dutch master if he had a match, he took a look at my meager little tinfoil packet, and said gravely, “This is not sheet.” At that, he tore it up, and threw it into the canal.

“Are you a traveler?” he asked, as he produced a huge block of tinfoil, ripped off a fistful of yellow hash, and carefully wrapped it for me.

“Welcome to Amsterdam,” he said, as he walked off, across the bridge and beneath the shadow of Rembrandt’s church steeple, with his long golden curls waving in the breeze.

Back in Paris, Woodstock and Jimi Hendrix were the rage. When I mentioned that I had been there, I was accorded instant cred, but sought to avoid the Gauloises smoke and the intellectual discourse, which I could seldom follow. At one party, I cut out on the lingo, as it were, picked up a couple of drumsticks and began “playing” to the music, on the old parquet floor. When the song was finished, I looked up to see that a small gathering had surrounded me, and heard someone say, “Il est un batteur Américain!” which means, “He is an American drummer.” Emboldened, I took off on the next song, my long hair flying along to the beat as I wailed away senselessly.

After this, my final performance, a voice arose from the crowd. “Il était le batteur pour Jimi Hendrix a Woodstock!”

On another trip, the old truck I was living in with my girlfriend broke down outside of Portland, Oregon. It was sunset and we must have been a sight, alighting from that old green delivery truck that said, “Say it With Flowers,” on the back doors, and a roof I’d painted pink with a 50-cent jug of oil paint. The gas station mechanic told us we’d need hundreds of dollars and a new pressure plate for the standard transmission, but his estimate approximated the entire budget I had left to get back to New York.

A hippie in a greasy white cap and an impressive ponytail was idling in the corner of the garage, shifting a toothpick from one side of his mouth to the other, and listening in on our drama. He quietly approached the owner of the garage, and asked how much the part itself cost, which was $86. “Ya got eighty-six dollars?” he asked. When I answered in the affirmative, the hippie gestured for us to follow him, and led us to a little stucco house, next door to the garage. He put out a tray of weed, disappeared, and arrived a few minutes later with the new Chevrolet part.

It was getting dark when the hippie led me out into a backyard full of old Volkswagens. “I fix ’em,” said my new friend. “I take the engines apart, clean ’em up with a toothbrush, and rebuild ’em. Even got some split windshields!” Before I knew it, I was too stoned to speak, and reclining beneath my own truck, holding a gigantic apparatus that looked like the spine of a dinosaur. Our host quickly popped the new pressure plate in, and the next day, we all drove to Bagby Hot Springs, at Mt. Hood National Park. If you know where to go, there are little cabins in the woods, with tubs carved out of enormous tree trunks, fed with the warm and perfect waters of the hot springs.

There was always danger to be found on the road in those days, but friends and fellow travelers to be found, as well. I used to go to universities with my student film, “Acclaimed Stupendous,” and announce screenings from the student radio station. I asked everyone to bring their “books,” and they knew exactly what I meant!

It soon became apparent that certain avenues didn’t meet. One morning, after an all-nighter drawing a group of tiny diplomats arguing beneath a huge bomb to illustrate an article about the nuclear SALT talks, for The New York Times Week In Review, I decided to sample a tiny leftover joint, just to see what my drawing really looked like. This proved to be a very bad idea, as the combination of sleeplessness and the roach made it almost impossible for me to keep a straight face at my required personal appearance at the esteemed Gray Lady. It must have worked out, though, because the director of the SALT talks called the Times from the White House and asked for copies of my drawing.

I also recall discussing drug use with Frank Wess, at the old Lincoln Center Classical Jazz Festival, where I was peddling my posters. The jazz great, who played sax and flute for Count Basie, said, “All I can say about that is, if you’re gonna play high, you’d better practice high.”

At High Times magazine, I illustrated a regular column submitted by the mysterious “R Dope Connoisseur.” It turned out that “R” was a rather shy fellow, who liked to be let in on our party hotline. I later learned that he had graduated from Yale with George W. Bush and spent 10 years writing the most important biography of Adolph Hitler, among many other honored works.

All I can offer my children are these stories, and the wonderful old poster of Benjamin Franklin smoking a joint that my friend the late artist Peter Bramley gave me in 1976. I hope that my children, and all of the children of today, who have endured a fascist regime, and a pandemic, will be patient and wise with their newfound legacy.

I hope they can use it to find a way back to the things in this world which really connect us to each other.

Not “revenue,” but beauty, truth and friendship.

Pincus is an award-winning illustrator and longtime Soho resident.

Be First to Comment