BY STEPHEN DiLAURO | Purgatorio Shows, C.U.A.N.D.O., Group Shot, Art Slavery, In Order to Survive, Bring Your Serpent, The Voyage Continues… .

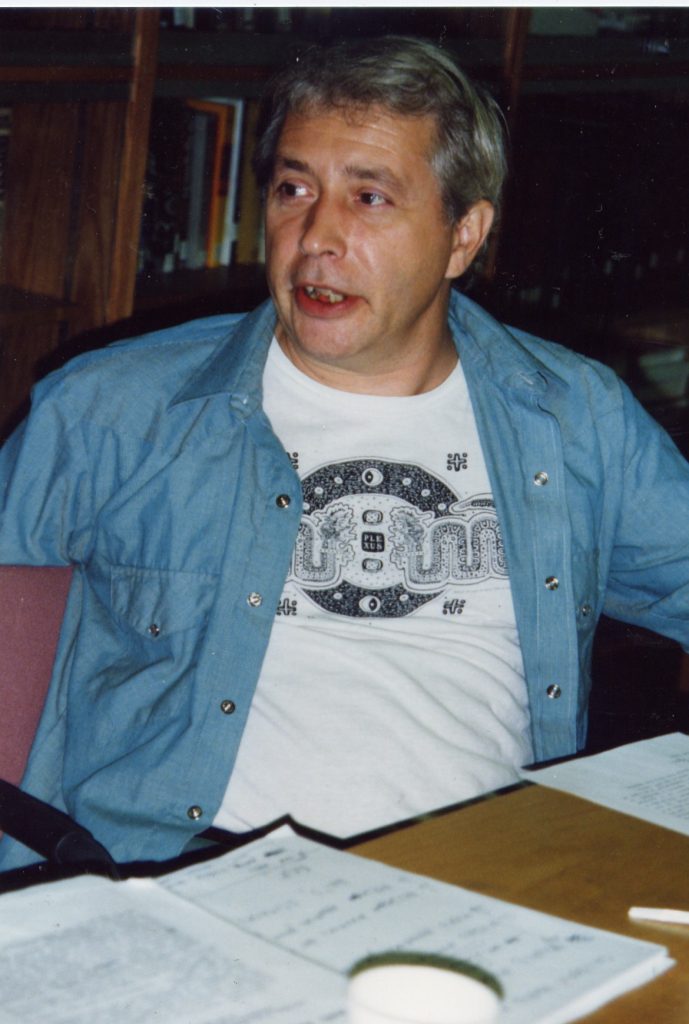

Many people will recall these phrases and words floating around the 1980s Downtown art scene. Something was going on that was the edgiest of the edgy. No one was quite sure what that something was but a lot of very talented people were part of finding out, in large part due to the energy of one person — Dr. Sando Dernini.

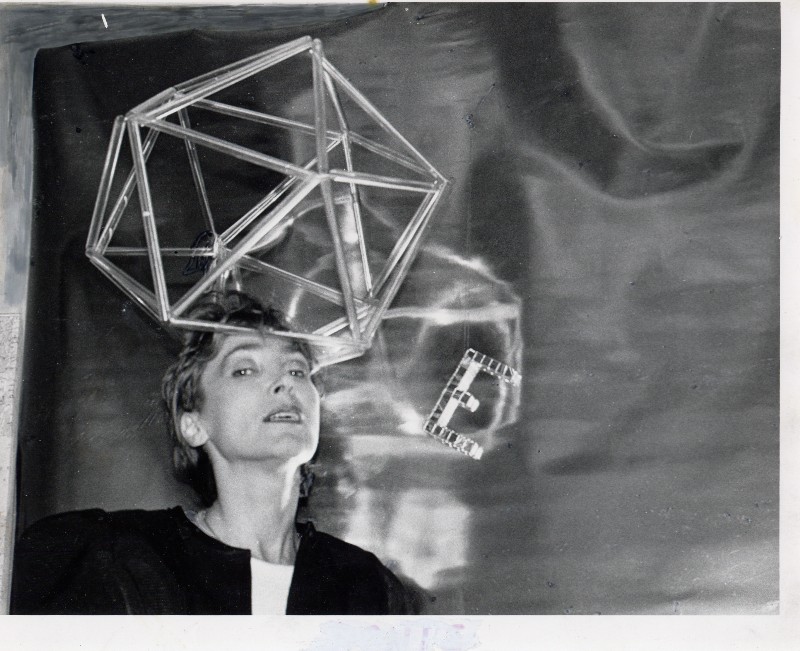

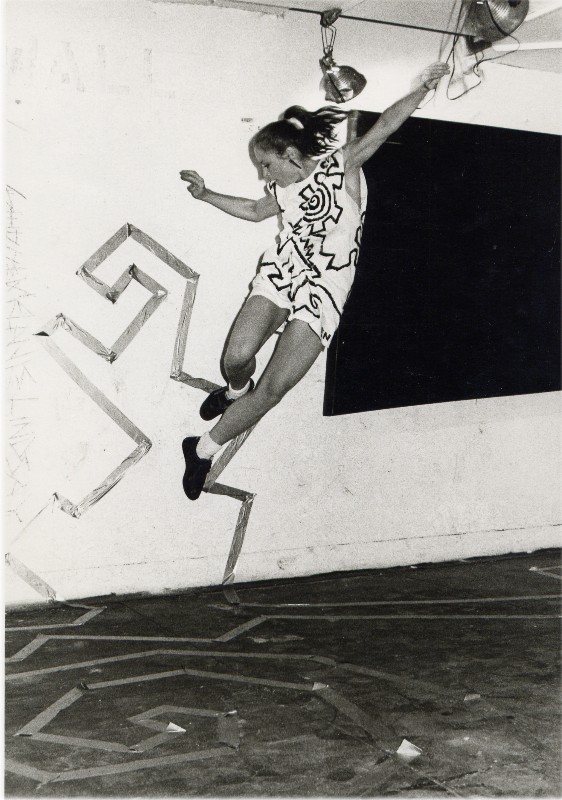

Dernini is the catalyst, the energetic intellectual spark that started a continuum that would, over the next 40 years, see more than 1,000 artists — jazz musicians, painters, scientists, poets, sculptors, playwrights, dancers, choreographers, performance artists, university professors and others — convene in locations around the world to create multicultural art events that came to be known as Plexus art operas.

From Manhattan to Sardinia to Dakar to Rome to Jerusalem to Sydney to Rio de Janeiro and beyond, these cross-discipline artistic experiments included community leaders, tech innovators, a two-time winner of the National Book Award for Poetry, the creator of a hit American TV series and others around the planet. Others, not as prominent or advanced in their careers, were also welcomed into Plexus. Along the way some of these folks changed their focus and did other things. Some dropped out of the art operas but continued as artists. Some died.

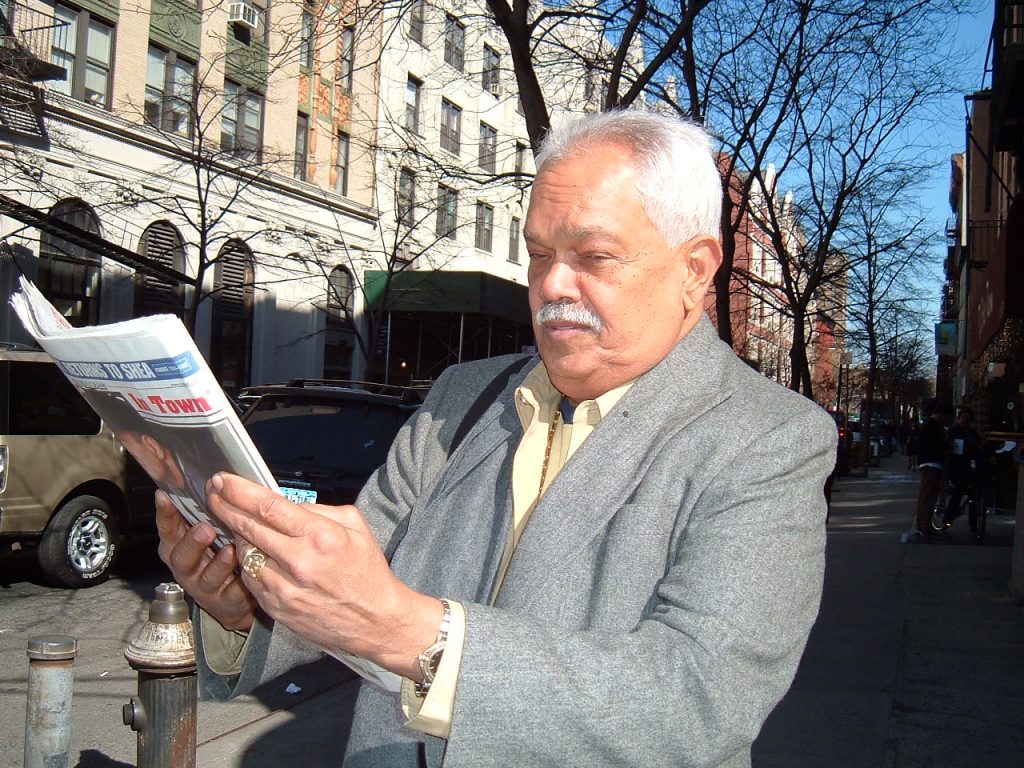

A couple weeks ago, I came to Rome to visit with Sandro Dernini, a friend over the last four decades, to talk about Plexus International and how it is that such a vast and sprawling exercise in free expression was ignored by the art world establishment and the mainstream media.

The “why” is simple: Plexus eschewed the idea of an art market at a time when capitalists of every stripe were colonizing the art world. Prices were artificially driven up to facilitate all sorts of financial chicanery, including money laundering. Of course, as little of those funds as possible was allowed to filter down to the actual living artists, as usual.

Probably the first example of this sort of shenanigan was the auction sale of van Gogh’s “Irises.” Sotheby’s loaned the winning bidder about half of the purchase price — at the time a mind-boggling $57 million. This market-making finagling would not come to light until two years after the fact. Of course, now 20th century artists regularly sell for prices well in excess of that amount. Da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” sold to Mohammed bin Salman for $450 million-plus in 2017 and hasn’t been seen since.

“Art is a biological necessity for human evolution,” says Dernini, who holds two Ph.D.s — one in art education and one in biology. “How is it possible that one person can buy art history and hide it away from the rest of the world? Art is food for the mind and the soul of all humanity.”

Asking such questions and positing such theories has not endeared Dernini and Plexus to the art world power structure.

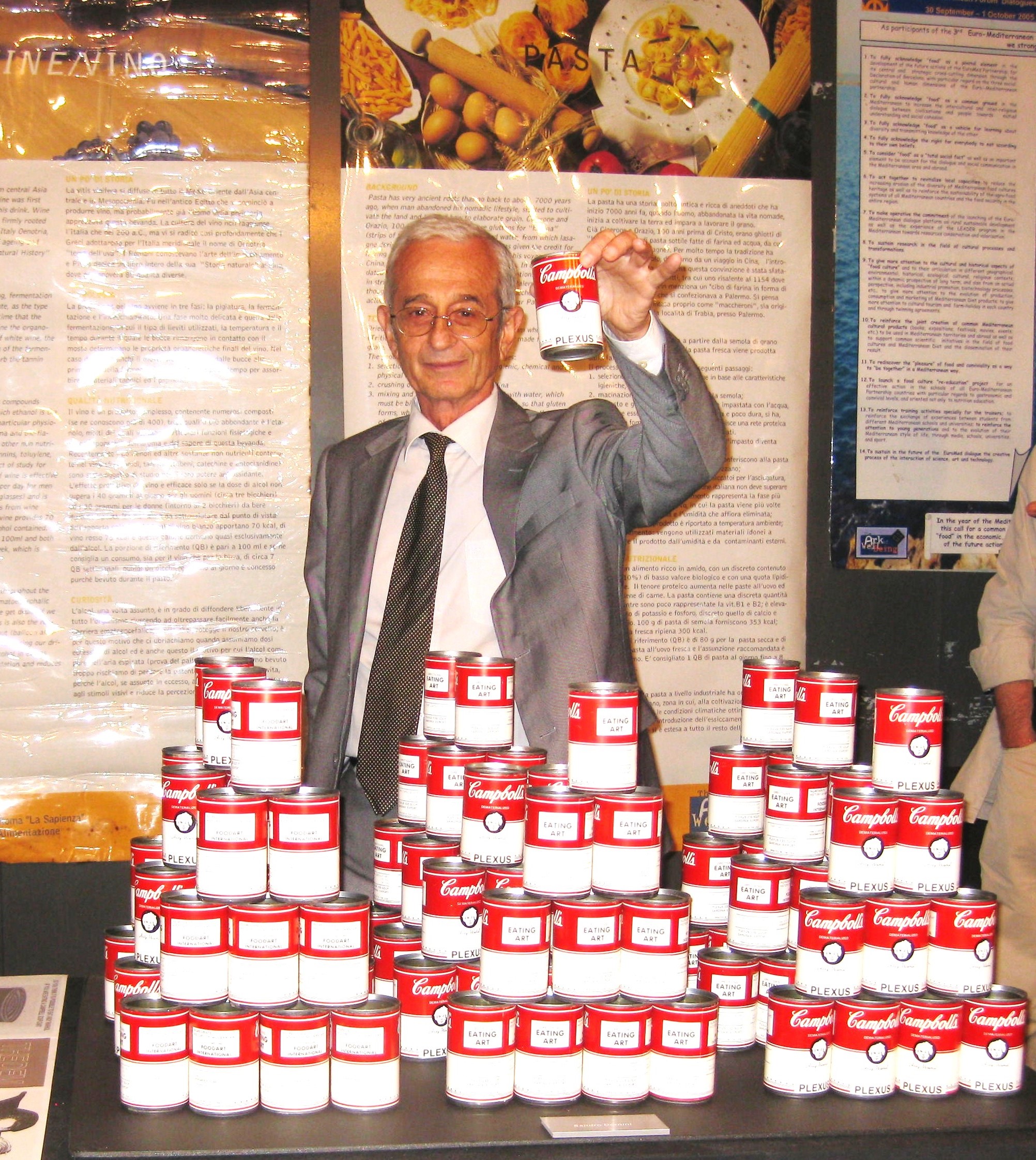

The idea of food as art became a part of the Plexus continuum, along with Eating Art — which led to one of the strangest art events ever. More about that anon.

While the ideas espoused by Dernini may have offended the money-grubbers, actual artists of repute and accomplishment joined the Plexus efforts because they subscribed to the theories Dernini put forth about art and community. The late Miguel Algarin, the award-winning poet and co-founder of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, and Miguel Pinero, the late playwright (“Short Eyes”) and creator of “Miami Vice,” were co-creators in the Plexus art operas, along with so many others. Algarin traveled to Dakar, Senegal and the Italian island of Sardinia with Dernini.

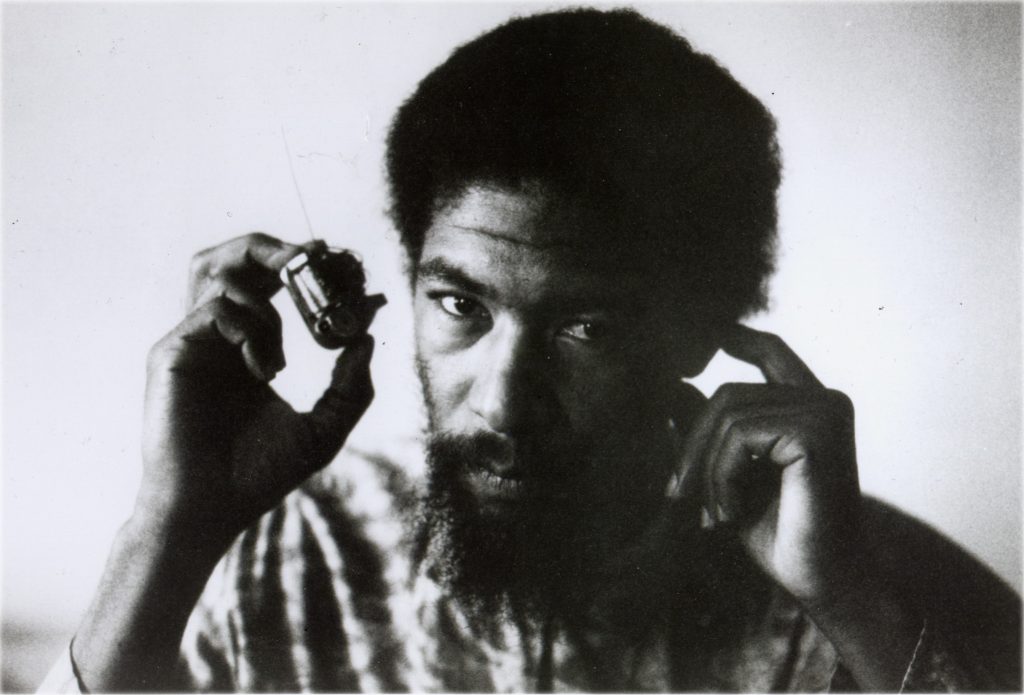

William Parker, who the Village Voice called “the most consistently brilliant free jazz bassist of all time,” coined the phrase “in order to survive” to describe the Plexus shows, and he is still in regular contact with Dernini. The late pocket trumpeter Don Cherry, who I had the honor to play with on some gigs, contributed his talent and resources to Plexus art operas.

The late Lawrence “Butch” Morris brought his orchestra with him to play in the art operas. The choreographer Gloria McClean and her sculptor husband Ken Hiratsuka participated. Joanee Freedom and Garrick Beck, co-founders of the Rainbow Tribe of Living Light (Rainbow Gatherings), were there from the start. Gretta Sarfaty, one of Brazil’s leading contemporary artists and former London gallerist, led the way in creating the art opera “Goya Time” at C.U.A.N.D.O. (Culturas Unidas Aspireran Nuestro Destino Original), at 2 Second Ave., along with her late husband, the avant-garde filmmaker and video pioneer Joseph Beuys and publisher Willoughby Sharp.

Likewise, scientists from Carnegie Mellon, N.Y.U., the University of Cagliari (Sardinia) and The Cooper Union added their computer expertise to Plexus, especially the art opera “Who Killed Heinrich Hertz?” conceived by Willoughby Sharp and led by the late computer science innovator George Chaikin, who is remembered for creating the groundbreaking algorithm that allowed computers to understand and execute curves. (The Pentagon glommed onto this algorithm to create a missile-guidance system still used today. Chaikin refused to accept any royalties on his invention, for moral reasons.)

“Who Killed Heinrich Hertz?” — a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the groundbreaking physicist’s birth — was also the first multi-location, virtual-participation performance ever held, in 1986 and before the Internet, using bit scan and slow scan technology.

From its inception in 1982, Plexus always included themes of social justice in the art operas, such as freeing Nelson Mandela, environmental concerns, all human rights for all human beings, equality of the sexes, ending hunger on planet Earth and acknowledgement that we humans are one race. Dernini, while continuing to organize more than 100 Plexus art operas over 40 years, became an expert with the United Nations programs promoting well-being and nutritional standards. Currently, he organizes an annual international conference on food and sustainability for the Mediterranean region.

Which brings me back to the Plexus themes of Food Art and Eating Art. On the evening of Feb. 21, 1987, Dernini organized a ritual “last supper” of Campbell’s soup as a performance with 12 artists, at a loft in Soho. It was titled, “Eating Andy Warhol.” The next morning, Andy Warhol died in his sleep at age 58.

None of the artists, including Dernini, knew that Warhol had gone into the hospital for routine gall bladder surgery. Was it a coincidence or something paranormal? Who knows? It was an event that influenced me and was recounted in two of my plays: “The Secret Warhol Rituals” (produced in 1995) and the recently written, yet-to-be produced “Dinner with the Devil.” (Inquiries welcome.)

Whether “Eating Andy Warhol” and his death were connected is irrelevant. It makes a damn good story.

There are so many artists, scientists, educators and performers who participated in Plexus over the decades. Now, there are even second-generation artists who grew up in Plexus and participate as adults. During my own participation in Plexus over the years, Dernini assigned me official titles: dramaturg and impresario. Looking back, it seems others contributed so much more. Sometimes I recall doing no more than observing with enthusiasm.

At 40 years, Plexus is the longest-running avant-garde art movement ever. For example, Dadaism lasted about 15 years. Fluxus kept on for less than 20 years. How is it possible that the Plexus art operas are barely a footnote, if that, in contemporary art annals?

My visit to Rome turned out, in large part, to be an effort to remedy this situation. Dernini and I spent our time together every day working on a proposal for a multi-episode documentary series about Plexus and the art operas. The Plexus archives — including videos, photos, written records, artworks and more — are meticulously catalogued and organized here in Rome. All that’s required now is an established documentary production company.

Dernini, now 73, lives with is life partner, Glaucia Coelho Demnjour, a Brazilian food artist and photographer, in a sprawling penthouse overlooking Via Portuense in Rome.

Reiterating what he has espoused since the beginning, Dernini told me, “For me, in addition to art as a biological human necessity, Plexus must be about environment over economics, ethics over aesthetics, community over art world stardom, human love over greed. Hopefully, we can get the rest of the world to think more about these ideas, through art.”

Time may be running short. But it’s still worth a try.

DiLauro is a playwright and roving cultural correspondent for The Village Sun.

Be First to Comment