BY PHYLLIS ECKHAUS | On Aug. 26, we celebrate Women’s Equality Day, the 103rd anniversary of passage of the 19th Amendment giving women the vote. And we can use that auspicious occasion to relish a bright facet of Greenwich Village history. The Village — home to artists, writers, rule-breakers and change-makers — was a hotbed of women’s suffrage activists.

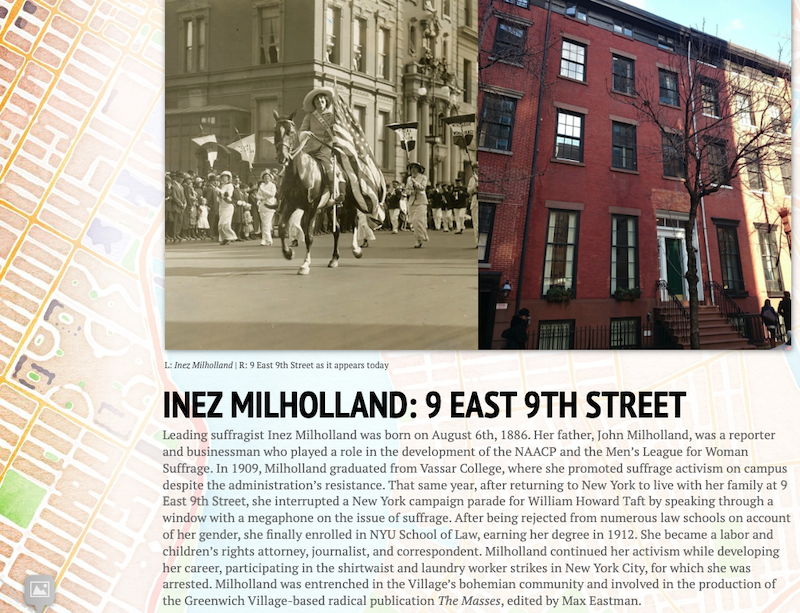

Indeed, if you’ve ever chanced upon a photo of the beauteous Inez Milholland mounted on a horse and leading a suffrage march, you’ve begun to make the Village connection. The year after Milholland graduated from New York University Law School — she attended classes on Washington Square in the 1895 building that now houses N.Y.U.’s Grey Art Gallery — she was at the head of two historic 1913 marches. Milholland led 30,000 suffragists down Fifth Avenue and months later fronted the first national suffrage march along Pennsylvania Avenue, where she charged into a horde of hostile and drunk male rioters, beating one off with her riding crop.

Onlookers gawked at the suffrage spectacle. For women to march was shockingly transgressive. At a time when respectable women were confined to home, women out in public were assumed to be out for no good, and possibly prostitutes. Marching, one marcher recalled, was a “privilege supposed to belong exclusively to men.”

The reputation of the Village made it a magnet for suffragettes, the once-pejorative term that radical suffragists embraced. Today, Village Preservation has published an online map of suffrage landmarks in our neighborhood, a great tool for self-guided tours.

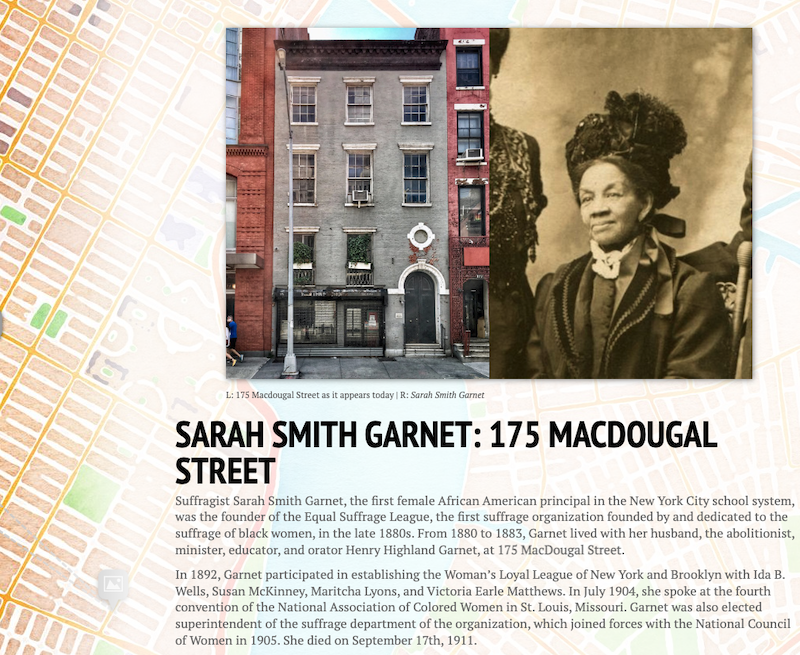

The map features an array of Village locations encompassing the many decades of the fight for the vote, and includes the women of color and working-class women whose contributions to the cause were long overlooked. For example, Sarah Smith Garnet, the city’s first female African American principal, founded the pioneering Equal Suffrage League to advocate for Black women’s suffrage and lived at 175 MacDougal St. from 1880 to 1883. L.G.B.T. trade unionist Rose Schneiderman, who eloquently linked suffrage to the uplift of struggling women workers, lived at 57-59 Second Ave. The Great Hall of The Cooper Union, at 7 E. Seventh St., witnessed countless historic suffrage meetings and celebrations, among them an 1860 women’s rights convention with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the 1916 rally that raised $100,000 for the successful 1917 campaign to win women’s suffrage in New York State.

Off the map is the institution that helped draw Milholland and her troublemaking peers to the Village. Remarkable numbers of daring, ambitious women gravitated to N.Y.U. Law School, the first U.S. law school to accept, recruit and graduate women in significant numbers. By 1920, N.Y.U. Law had graduated 303 women, far more than any other school.

As Elinor Byrns, N.Y.U. Law Class of 1907, observed, some of those newly minted women lawyers were “revolutionists” — their subversive zeal honed by the fight for feminism and suffrage. Byrns herself organized suffrage marches, served as the publicity director for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), and ran for office on the Socialist ticket in 1917, after New York State gave women the vote. Byrns’s campaign fliers proclaimed, “Let’s Send a Housekeeper to Congress!”

Law school alumna revitalized the fight for suffrage. Crystal Eastman, Class of 1907, joined Alice Paul and Lucy Burns in Washington, D.C., to form a history-making troika, the three-person congressional committee that jumpstarted the fight for a federal suffrage amendment. Their strategic shift away from state suffrage campaigns ultimately won the 19th Amendment.

For Crystal Eastman, suffrage was a family affair. Before her brother Max took the helm of The Masses, the radical Village monthly, he launched the Men’s League for Woman Suffrage out of his Village apartment at 118 Waverly Place.

Jessie Ashley, N.Y.U. Law Class of 1902, daughter of a railroad president and sister of the law school dean, strenuously sought to make NAWSA class-conscious. Herself the onetime lover of “Big Bill” Haywood, the leader of the Industrial Workers of the World, she served as NAWSA’s national treasurer and implored the “handsome ladies” of NAWSA to be “rid of mere ladylikeness” and focus on recruiting working women to the suffrage movement.

N.Y.U. Law grads pioneered media-savvy strategies under the leadership of Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Bertha Rembaugh, Class of 1904, discovered there was no legal bar to women being poll watchers. Beginning Election Day, Nov. 2, 1909, members of Blatch’s Equality League — who as women couldn’t vote — watched the polls, resulting in some scandal.

But it was Inez Milholland — the stunning and seductive daughter of a former newspaperman — who excelled in attracting media attention. In 1913, she proposed to and married Eugen Boissevain, prompting a New York Times headline lamenting “the taking of Milholland by the Dutch” as her new husband was a Dutch citizen. To Milholland’s shock, upon her marriage to a foreigner, she lost her citizenship and her license to practice law. Under federal law, her legal identity was subsumed by her husband’s.

Still, Milholland did not lose her fervor for suffrage. In the midst of a grueling 1916 suffrage speaking tour, she collapsed. Her death, weeks later at age 30, made her a martyr of mythic appeal. Milholland’s demand of Woodrow Wilson — “How long must women wait for liberty?” — multiplied across suffrage placards and banners. Suffrage “general” Alice Paul deployed Milholland’s tragic demise to launch the campaign of White House picketing, arrests and hunger strikes that riveted the nation and finally helped secure the vote.

Thanks, Phyllis, for such an interesting and informative article.

And I agree with Margo!

Would be a great walking tour!

Jane Williams

Thank you for writing this article. I look forward to sharing it with my daughters as we walk around the neighborhood.

This was an interesting read, Phyllis. Thank you!

Phyllis, great article, great research. You’ve found your audience and your stride! Look forward to more.

Phyllis, did you ever consider taking interested folks on a ‘tour’…an educational, fascinating tour, led by the author of the above…

Margo Moss

Thanks for the article but please, can’t even the progressive Village Sun get it right? It’s Suffragists not the diminutive ‘suffragette’.

Thanks but as I note in the article, radical suffragettes made the once-pejorative term their own.

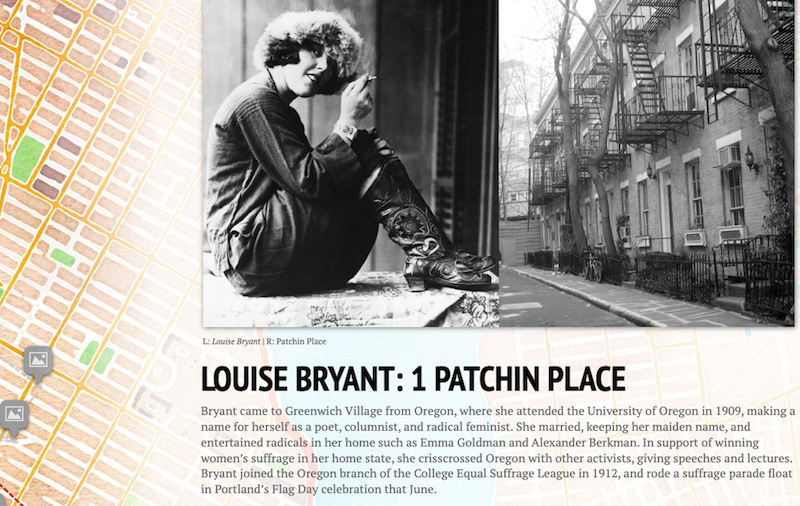

I often thought of the renowned residents of Patchin Place, including Louise Bryant and E.E. Cummings, when our kids were going to school next door, at P.S. 41.

Bryant was played by Diane Keaton in the 1981 film Reds, and her lover, John Reed, was played by Warren Beatty. I happened to walk past the building on West Tenth Street that was supposed to be the home of Eugene O’Neill, one evening, just as Diane Keaton alighted from the front door in the vintage guise of Louise Bryant.

It looked like Diane Keaton was just merely supposed to descend the stairs to he street, and keep walking, but the director wasn’t satisfied. I watched about five unsuccessful takes, until an old woman, who obviuously lived in the building, opened the front door, and angrily confronted the lights and cameras as she held two bags full of household garbage. After issuing a vivid and profane tirade at cast and crew, the woman dumped her refuse in a nearby receptacle, turned, and went back into her domicile.

“Cut, PRINT!!! yelled the director, Warren Beatty.