BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Updated Dec. 5, 11:30 a.m.: A new documentary about Corky Lee, the crusading Chinese-American documentary photographer, helps add to the growing appreciation of an unsung local journalistic hero.

Lee died of COVID in January 2021 at age 73.

He was born Young Kwok Lee in Queens. As a youth, he helped out working in his family’s laundry business. Finding his calling as a photographer, he would go on to relentlessly document all aspects of the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) experience in New York, from Lunar New Year to street protests, from Pakistan Independence Day to Diwali and more.

As word of Lee’s passing was reported in local outlets like The Village Sun, it soon snowballed and became a national story picked up by the mainstream and international media. In death, the modest Lee was finally getting the wider recognition that he had always so rightfully deserved.

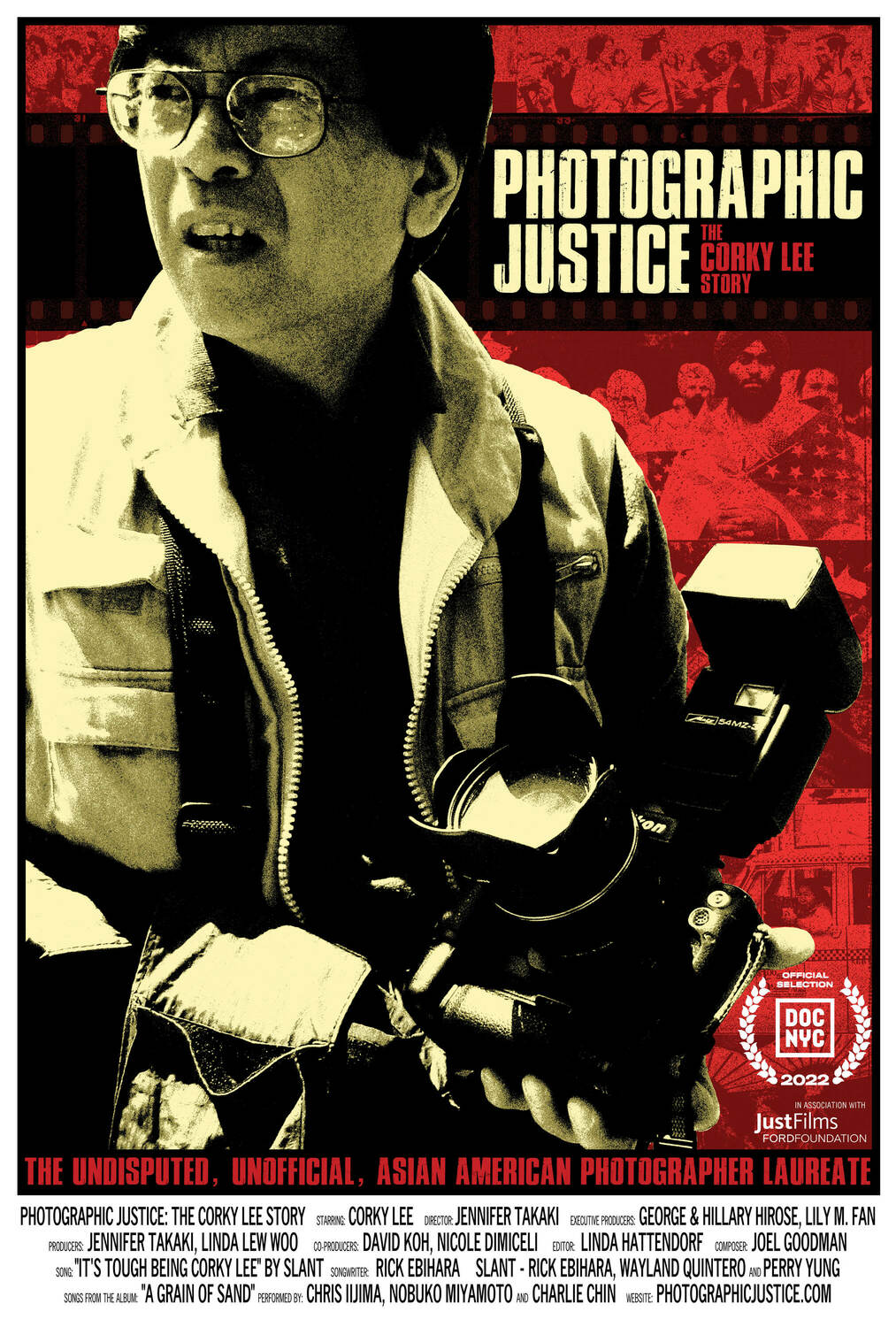

Director/producer Jennifer Takaki spent more than 19 years working on “Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story.” The finished product screened on Nov. 12 at the SVA Theatre as part of the DOC NYC festival, America’s largest documentary fest.

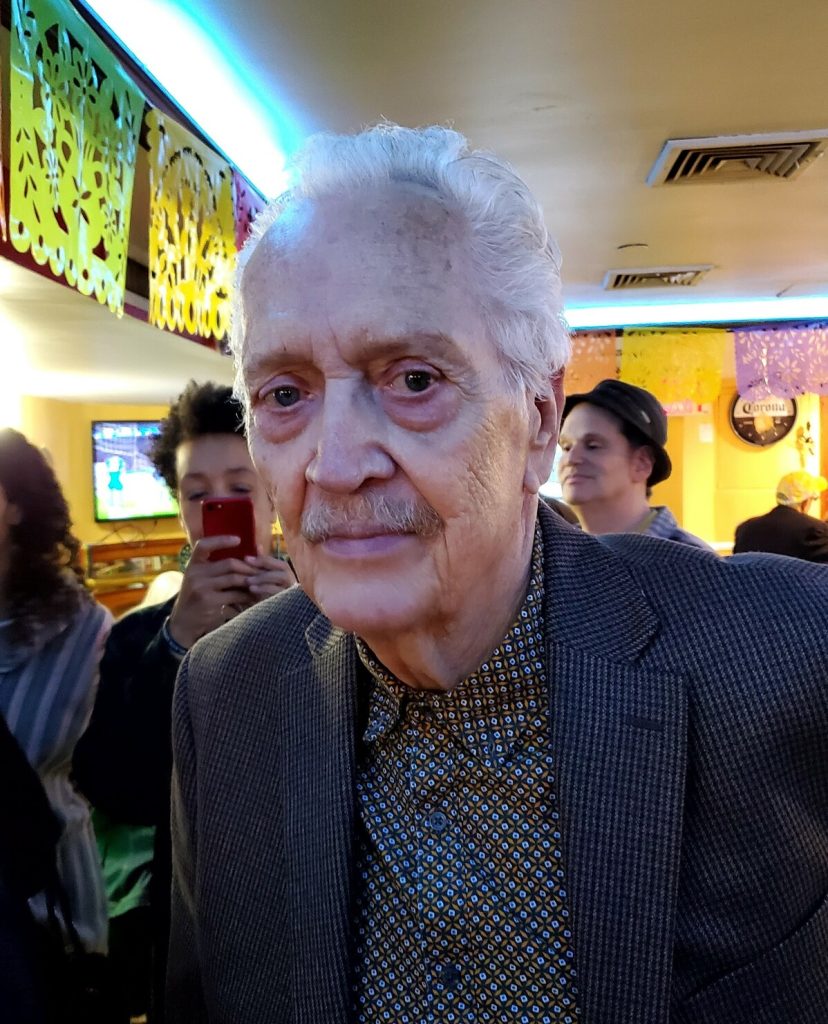

Although he was always out and about in public with his camera, Lee was intensely private. Takaki’s film shows us the man behind the lens.

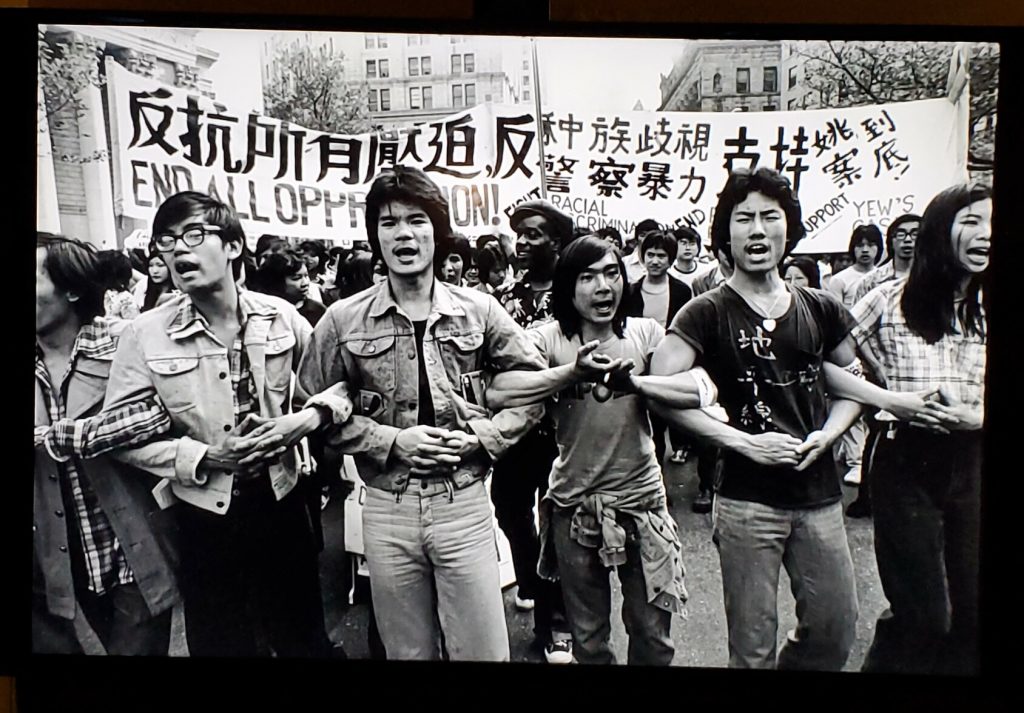

Lee’s humorous, almost self-deprecating, moniker was the “undisputed unofficial Asian American photographer laureate.” To his chagrin, however, early on, after he broke into the daily newspapers by covering protests, he became pigeonholed by the media as “the Asian demo photographer.” But he was much, much more than that.

The film reveals Lee as intensely driven — wise, articulate, creative, with an unflagging passion to chronicle the lives and events of Asians in this country in all their facets, to help them carve their rightful place.

He actually started out as an organizer in Chinatown, working on tenant issues and fighting to insure that at least some of the construction workers who built the Confucius Plaza apartment complex by the Manhattan Bridge were from the Asian community.

In one famous instance, in 2014, Lee used his lens to help right the historical record, restaging the classic photo of the driving of the “golden spike” on the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah. Only this time, his subjects were the descendants of the Chinese railroad workers who were excluded from the original photo.

Another time he traveled out to California to photograph a woman’s garden full of discarded toilet bowls that she had repurposed as planters. When whites had moved into homes formerly owned by Asians, they had all the toilets replaced.

He covered a New York City demonstration by Chinese women outraged over Opium perfume, charging that the Yves Saint Laurent fragrance’s name evoked painful memories of mass addiction fomented by the British.

But Lee also covered lighter subjects and many slice-of-life events, like the Nathan’s hot dog eating contest in Coney Island one year because it had two Asian women competing. It was important for that one to be firmly planted into the historical record, too, he insisted.

We also see the personal Corky. We learn about his demanding, emotionally distant father, who wanted him to be either a lawyer or a doctor. However, Lee knew inside that he would only be happy if he was doing something “creative.”

We see footage of an utterly devastated Lee talking about the loss of his wife — then later reflecting on finding love again with a younger photographer, Karen Zhou, who, he admits in the film, helped him to slow down “and smell the roses.”

In fact, Lee was so committed to his documentary photography work that, as he notes in the film, it was hard for him to take any time off — even just a single day — to work on a book project he had long been trying to do.

We even see him doing his old-school film-developing process (he never lost his love for traditional camera film, preferring it aesthetically to digital photography), as well as his meticulous archiving system, how he filed away all his countless photos and negatives.

Takaki said she was inspired to film Lee after meeting him at an event in 2003.

“I just wanted to do a five-minute video and put it on YouTube,” she quipped of how things started out. “Because Corky was so private, no one really knew Corky at all. I knew when I met him, I knew he was underappreciated. The idea was to give him a platform, so he would have a wider audience.

“That was his passion, that was his soul,” Takaki said, “documenting the community.”

Artist George Hirose, one of the film’s producers, said that, through Lee, he came to appreciate pan-Asianism, feeling that “it’s more powerful” than being siloed into separate Asian ethnicities.

Lee was able to see a rough cut of the final film before he died.

In related news, a book of Lee’s photos will be coming out soon published by Penguin Random House.

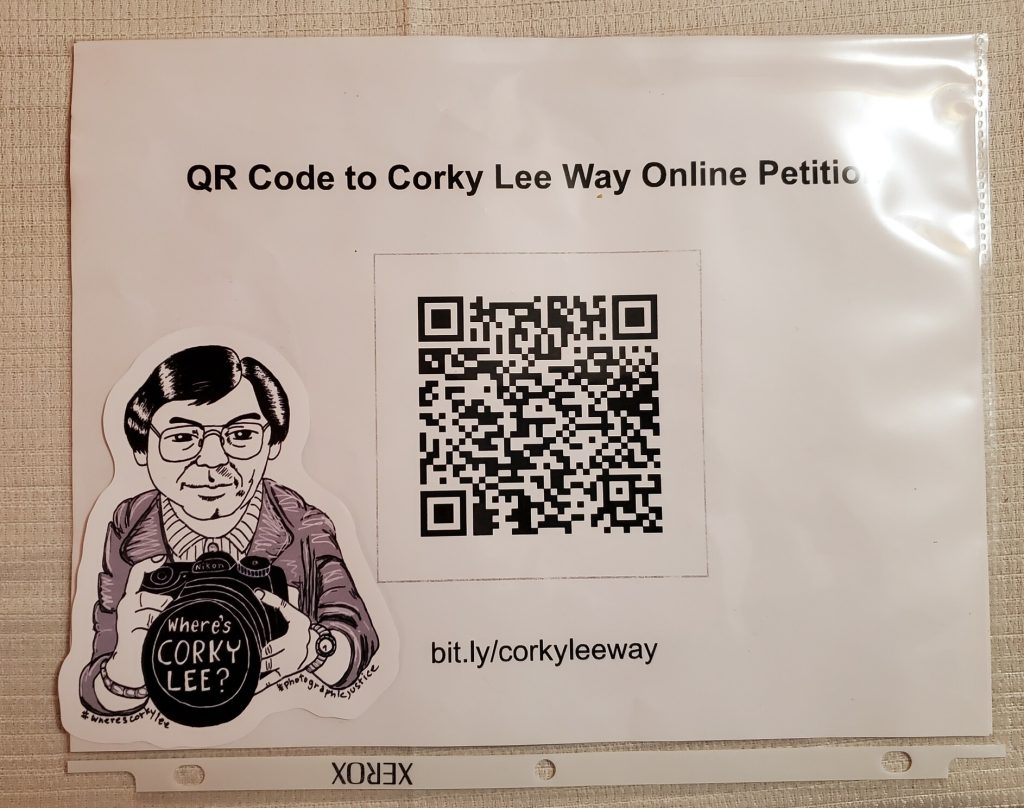

Also, a petition effort is afoot to rename the one-block-long Mosco Street in Chinatown as Corky Lee Way. (The steeply sloping street is currently named after community organizer Frank Mosco, who, among other things, helped create the Two Bridges Little League.)

In addition, “Photographic Justice: A Tribute to Corky Lee” — a curated photo exhibit featuring images by Lee’s friends and colleagues that evoke his spirit and values — will be on view through the end of December at the Charles P. Sifton Gallery, in the U.S. Courthouse for the Eastern District, at 225 Cadman Plaza East, in Brooklyn. The courthouse gallery’s hours are Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Be First to Comment