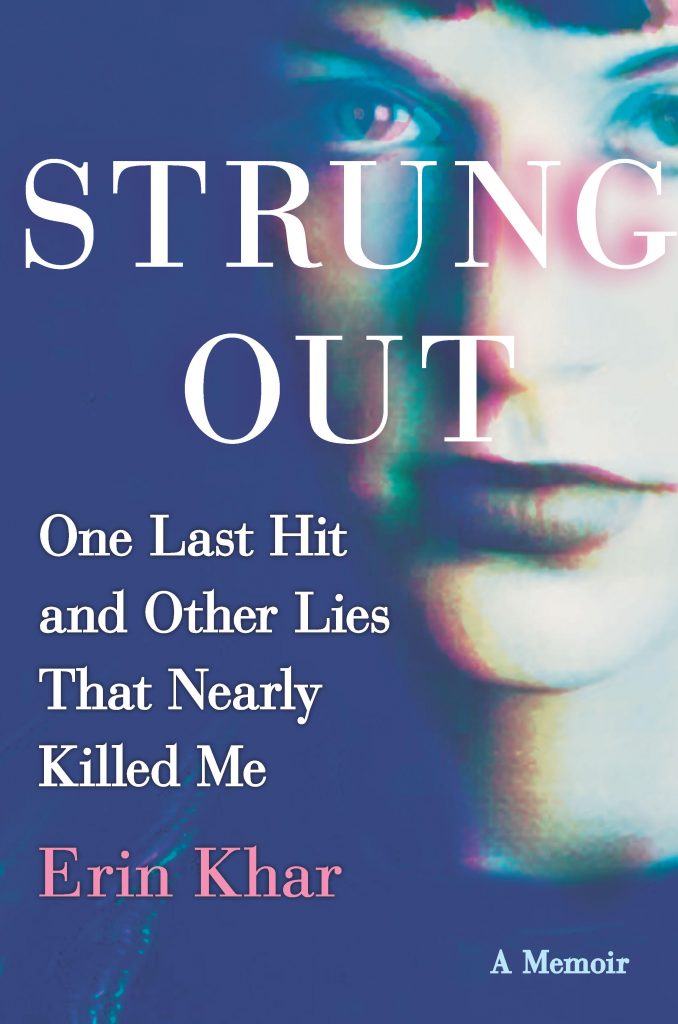

BY LETICIA LABRE | No wonder Greenwich Village has such an electric vibe. It is overflowing with residents who have riveting stories to tell. One such resident is Erin Khar, who recently published her addiction memoir, “Strung Out: One Last Hit and Other Lies That Nearly Killed Me” (Park Row Books).

The memoir itself is addicting, following Khar’s journey from the time she started stealing pills from her grandmother’s shelves when she was 8, to finding the strength to get clean in her late 20s as she gave birth to her first child.

Khar is an editor at Ravishly and the author of the wildly popular advice column “Ask Erin.” (She’s made all the mistakes, so you don’t have to). Of Persian/Swedish descent, she is 46 and has been drug-free for 17 years.

A California native, she finished her B.F.A. at The New School. She lives with her husband and two sons in Greenwich Village.

I recently caught up with Khar to discuss her book, her writing process and her insights on addiction.

L.L.: Erin, congratulations on your memoir. The addiction memoir genre is so popular. How did you differentiate your work from others in the field?

E.K: Thank you. While there have been other addiction memoirs written by women, I think what sets my book apart is that it’s written from the point of view of a young female heroin addict. There’s an extra stigma attached to heroin compared to other types of addictions. I wanted to explore that and help destigmatize it, so that it can be more effectively addressed.

The book is such a gripping read. It’s shocking, heart-wrenching and even hilarious. What enabled you to be so honest?

The distance of time, therapy and working on myself helped. Also I didn’t want to write anything that wasn’t completely honest. I wanted people to see beyond caricatures, and grasp the full picture of what the experience is like. Yes, there were some horrible moments. I lied, I stole, but I was also a human being.

What do you want readers to come away with after reading your book?

I want readers to realize that addiction is not a moral failing. It’s a human condition that people struggle with. In sharing my story, I want people who have experienced addiction, or who have loved ones who have, to feel a renewed sense of empathy and compassion. I want them to feel less alone, and feel less shame.

I hope the book encourages people to talk about addiction in both public forums and at the dinner table. Approximately 50 percent of Americans have a family member or close friend in the throes of addiction. There are over 20 million Americans struggling with a substance use disorder. One hundred and thirty Americans die every day of opioid overdose. This is not a rare problem. There is still so much stigma and judgment attached to it and that’s what I really hope to erase.

In your book, you openly share that racial and financial privilege played a huge part in your struggle with addiction and recovery. Can you talk more about that?

Addiction memoirs are popular with some readers. But many more people only see addiction through what’s reported in the news, in the wake of the opioid crisis. Those images are caricatures of what the struggle looks like. Part of the reason I was able to hide my struggle for so long was because people around me had a preconceived notion what addiction looked like and I wasn’t it. In sharing my story, I hope to shatter preconceptions because they’re a stumbling block to giving and receiving help.

I was struck by the flow of your writing and how you were able to combine incredible detail with pace and poignancy. Can you talk about how you found your writing style?

Aspects of certain books influenced me. Through Elizabeth Wurtzel’s “Prozac Nation,” I realized I wanted my voice to have an intimate relationship with the reader, so that it really felt you were in there with me. Lidia Yuknavitch’s “The Chronology of Water” showed me the importance of writing from the body. Sometimes, I put on music, closed my eyes, and literally just sat with how my body felt during specific moments in my past.

As for my voice, part of it was practice, and just not wanting to sound like anyone else other than myself. I wrote the first draft very quickly. There was very little intellectualizing about it, which helped it come out in an authentic way.

You’ve talked about policy work. Could you expound on your plans in this area?

I’d like to continue speaking on panels with policy makers and law enforcement officials. I hope we move away from punitive policies, toward meeting people where they’re at. I’m talking about harm-reduction services. Heroin users who go through the traditional rehab model experience a nearly 80 percent relapse rate. It’s about half that for those who enter treatment through harm-reduction services. This includes interventions that are controversial but proven to be effective, like medicated assisted treatment, access to stable housing, safe injection, fentanyl testing strips, and needle exchange programs.

People who go into treatment by first accessing harm-reduction services are much less likely to relapse. A big part of that is because they’re walking into services without feeling stigmatized and judged.

What was the best part about writing a memoir?

The best part by far is connecting with people and finding out what resonated with them. Knowing that my work helped people feel seen or gave them new understanding is very rewarding.

I’ve been trying to find a book I read Manny years ago and can’t remember the name. It was about Greenwich Village. One off the main character is named Nell. Does this one have her? Or would you have any idea on the one I’m looking for. Thank you