BY JUDITH MAHONEY PASTERNAK | Longtime West Villager Evan Morley, a former executive editor whose home was a cauldron of radical feminist thought during the 1970s, died Oct. 1 of kidney disease after a long battle with cancer. She was 88 and died in the Perry Street apartment where she had lived for more than 50 years.

Morley was not a women’s liberation movement luminary like her old friends, theorist Susan Brownmiller and novelist Alix Kates Shulman. Her name has appeared only once in The New York Times, decades after the heyday of radical feminism, in an article written about an ongoing weekly poker game at Brownmiller’s apartment: “Morley was a short, gray-haired woman with a weathered, impish face, who would describe her age only as ‘old enough to collect Social Security.’” (“The Poker Night Mystique: Veterans of Feminist Movement Meet to Raise Bets, Not Consciousness,” The New York Times, Feb. 10, 2000.) “In some sense,” Morley noted, “this poker group is a small remnant of a community of political women.” Indeed, the community as such had largely dissolved by then, but its members still influenced much feminist thought.

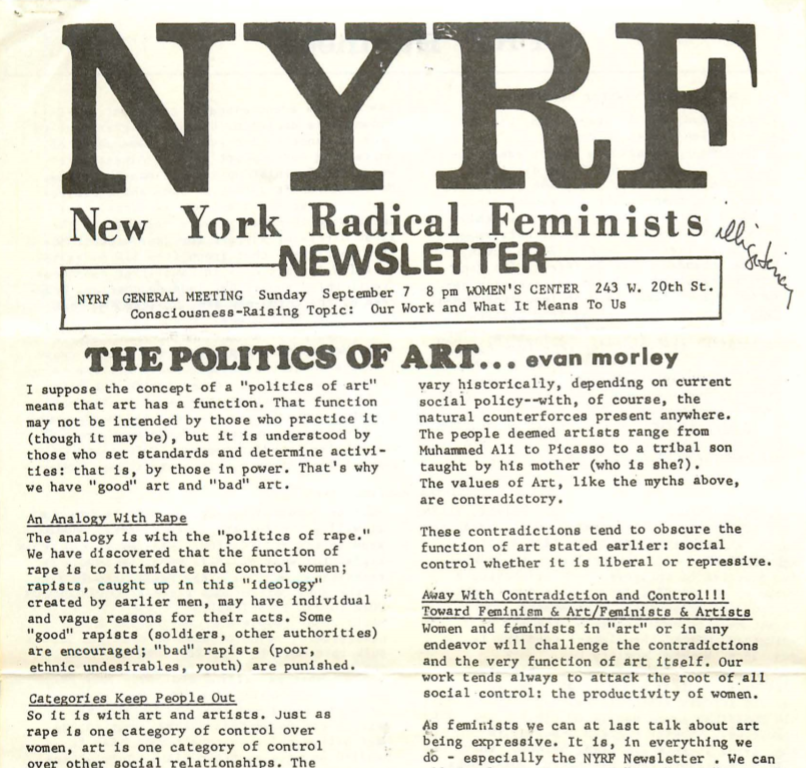

Morley’s contribution to that feminist thought was as a facilitator, a mover and shaker who, without holding elected office, puts candidates and constituents together. Earlier, she had been a leading figure in New York Radical Feminists (NYRF), whose groundbreaking conferences on rape, prostitution, marriage and motherhood brought small-group consciousness-raising to larger audiences. In the smaller venue of her Perry Street living room, she hosted gatherings that were part ongoing salon and part floating women’s center, a recurring brainstorming party where ideas were tossed around informally and fruitfully.

She may have looked “weathered” in 2000, but the age she would not give was in fact barely old enough to collect Social Security — she was 65. She was born in Upstate New York’s Lake Placid, and her last name at birth was not Morley, but Epstein. As a teenager in Lake Placid, she met the slightly older Shulman, and a few years later she and Brownmiller were classmates at Cornell. It tells volumes about her character that seven decades and counting later, she still numbered them among her close friends.

Around 1954, she left Cornell, changed her name to Evan Morley (it was about the same time that Susan changed from Warhaftig to Brownmiller) and came to New York City, where a succession of jobs led to the editorial work that became her career. Early on, she found jobs for Shulman, who had also arrived in New York. That too became a pattern; decades later, as a senior editor of books like “Nancy Drew Secret Codes” and series like “Your Day-to-Day Horoscopes,” she would parcel out paid subediting work to the women who came to Perry Street.

Morley herself, though influential, was hardly doctrinaire. She was a slight, elfin lesbian who wore trousers and tweed sports jackets, smoked Lucky Strikes and, as noted above, played poker. Yet at a time when many feminists were politicizing their sexual orientation, she treated her lesbianism as a personal preference, like the Lucky Strikes.

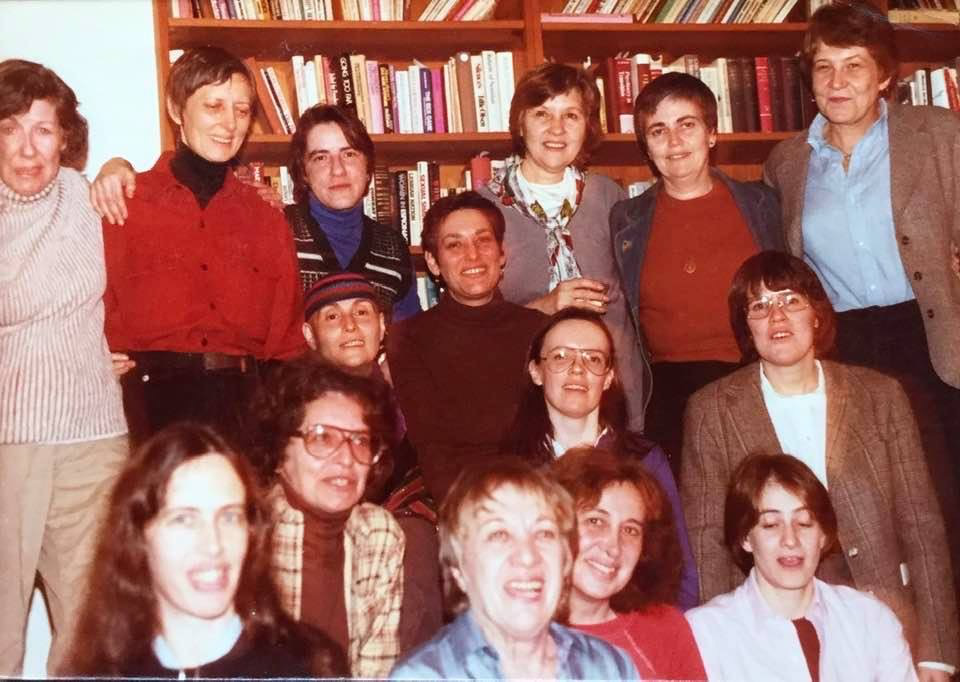

On almost any evening in the Perry Street apartment, a young lesbian like Deborah Glick, who would later become a fiery advocate for gay rights and women’s reproductive freedom in the New York State Assembly, might meet and talk with women who were articulating those ideas. Brownmiller was a frequent visitor, as was the late Florence Rush, author of “The Best Kept Secret,” the first feminist work to politicize the sexual abuse of children. So were Noreen Connell, co-author of “A Sourcebook on Rape,” and gay historian Karla Jay, author of “The Amazon and the Page: Natalie Clifford Barney and Renee Vivien.” Also part of these gatherings were women who were putting feminist theories into practice, like the late Dolores Alexander, a founder of Mother Courage, New York’s first feminist restaurant, and Fabi Oak, one of the founders of the Upper West Side bookstore Womanbooks. Eleanor Batchelder, a friend who cared for Morley in her last days, was another of the Womanbooks founders.

Morley believed passionately in the power of women, and always noticed their efforts and tried to support their projects with her enthusiasm, her ideas and labor, and her money. Lesbian projects were of special interest to her, and the Women’s Coffeehouse, which was open from 1974 to 1978, was one of her pet projects, providing both sustenance and socialability.

Morley personified the tenets of radical feminism in being always, first and foremost, a woman bent on living as she chose. One Thanksgiving, she invited a lot of women who were not with their families to come to Perry Street for a turkey dinner, only to find her oven out of order. Chelsea Dreher, one of that night’s guests, says Morley shrugged, set the roasting pan on a radiator, and served the dinner a little late. And in 1973, when the lead story in the NYRF newsletter contained assessments of a weekend spent at a women’s retreat in the Catskills, half a dozen women wrote about “sharing lifestyles, fears, hopes, and personal testimonies.” Morley’s dry comment was only, “A cocktail party is a valid form of alternate lifestyle.”

Now living in Paris, writer and journalist Mahoney Pasternak was a longtime West Sider and a member of New York Radical Feminists in the 1970s.

To my nieces, nephew, others in my family: I am sorry the only image with my name for all my time in the Women’s Liberation Feminist movement comes up with this article. It doesn’t represent my work or philosophy of my work at all.

A view of a 1970s collective-oriented feminist activist with 2020 social media celebrity-oriented eyes.

We shared many good laughs together on Perry St. as we reminisced about the good old days of the Village. Evan, you were a treasure and will be dearly missed!

Thanks, Lynne!

Judith

The photograph from my camera was from 1982 going-away party to San Diego for two of the women in the photo at Florence Rush’s home. Specifically about New York Radical Feminists: Evan kept the group going from 1972 to 1977 as treasurer, meeting space provider, newsletter publisher.

Viewing last century’s feminist collective member activism paradigm with this century’s feminist celebrity paradigm.