BY YUYAN LU | The first time Emi Nietfeld heard the term “disaster bisexuals,” she thought it was made up.

“This is the identity marker that I needed when I was in high school,” she said. “Not just bi, but disaster bi.”

Nietfeld, a 30-year-old former Google software engineer, was sitting outside her favorite East Village coffee shop, Ninth Street Espresso, where she wrote most of her buzzy memoir, “Acceptance” (Penguin). She wore a black knit top that highlighted a round, golden-pendant necklace, her hair combed behind her head and held by a hair clip. Her cheeks flushed in the sun, as she joked about the culture of iced coffee and her plan later to watch “Saturday Night Live” with her husband on the new sofa they bought together.

It was hard to picture her as the high school “disaster bisexual” portrayed in her memoir.

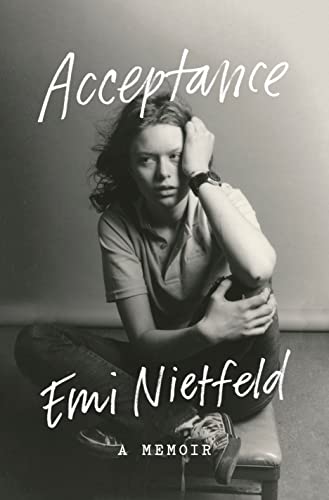

The book has been praised by New York Times bestselling author Bruce Feiler as “this generation’s “Prozac Nation.”” The Southern Review of Books called it “a gripping, urgent memoir in an era when social mobility feels beset from all sides.” The young East Villager’s memoir, published this past summer, chronicles her journey from foster care and homelessness to Harvard on a full scholarship and then on to a job in Big Tech.

In the probing narrative, through revisiting the hardships of the first 20 years of her life, Nietfeld questions the assumptions that survival should depend on personal excellence. In 2002, when Nietfeld was 10, her father came out as trans in days before the gender identity was well known, and her parents divorced. Her hoarder mother was given full custody while her father, who changed her name to Michelle, seemed to have completely disappeared from her life. They lived in a duplex in Minnesota where “the stench of mouse pee permeated every room.”

Later, Nietfeld was hospitalized at age 14 for anorexia at the Methodist Hospital Eating Disorder Institute. Her doctor told her that she could just choose to be well or to be sick “and get locked up for a nice long time.” But it didn’t make her any better, given the fact that her illness was not a “bad behavior” to fix, as she writes, but a condition compounded by a difficult home life.

“I don’t think it really works to tell people, “Oh, be tough,” she added.

Four weeks after physical therapy at Methodist, Nietfeld was sent to the Children’s Residential Treatment Center because she was deemed not stable enough. She was diagnosed with “psychosis,” which she believes she didn’t actually have. Nietfeld — not her pathological hoarder mother — was blamed for her own struggles, because why would a doctor choose to believe a teenager who “had recently been taken off her meds” over her “concerned mother who’d taken off work for an appointment?”

After Nietfeld had spent seven months in inpatient therapy, doctors and institutions recommended sending her to a foster family — though her mother objected, arguing she would be “losing her daughter.”

Nietfeld was ultimately sent to live with a family she knew nothing about, and at age 15 found herself struggling in the home of her strict Christian foster parents. She was told to “just be a teenager,” yet forbidden to ride in cars with her peers, then made to feel she was a burden by her foster parents, who complained of having to chauffeur her around.

“Do you think I want to spend my Friday night like this?” her foster mom asked.

The conflict culminated in Nietfeld coming out about her bisexuality, which seemed to threaten her conservative foster family. They demanded Nietfeld move out ASAP.

“In my family growing up, homosexuality was a sin, but bisexuality was worse,” she writes in “Acceptance.”

At the time, living in a conservative Christian family meant hearing that homosexuality was horrible, yet also that “people are born gay, therefore, it’s O.K. to be gay.” But no one told her whether bisexuality was O.K., Nietfeld recalled during the interview.

“That made it harder to even imagine that I could be bi, and let alone think that it would be O.K. to be bi,” she explained. “At the time that didn’t feel acceptable.”

She became mortified over the question of her identity.

“I’d be O.K. with being gay, but being bisexual still seemed so shameful I couldn’t even think about it,” she writes.

After moving out of the foster home, Nietfeld transferred to Interlochen Arts Academy, in Michigan, where she began to dream of another way to escape: getting into the Ivy League’s Harvard. To get accepted into the boarding school’s writing department, she wrote a gender essay about her father’s transition. for the first time, she opened her heart and told her true feelings about past experiences she usually kept hidden. Writing the article made her feel “a surge of power.”

Her father and her trans friends stretched her perception of who she could become.

“They made me believe that I could recreate myself — no matter who disapproved or tried to stop me,” she writes.

“It ended up becoming my college essay because it was so honest,” she said during the interview.

But her extreme candor about her trauma was not at first welcomed by admissions officers. In order to promote herself as the “perfect overcome,” she writes, she needed to rewrite her original essay to downplay the gory details of her experience. Even so, skeptical admissions officers still interrogated her closely.

When she wrote her memoir, Nietfeld realized she didn’t want to just pretend it was a simple story of overcoming — that her messy life and past trauma were more important than the brilliance of going to prestigious schools and working at big corporations.

“I am really critical of which stories we pick up on and say that is the important story,” she noted. “There’s all of these people who are around us who are super-resilient — but they didn’t go to Harvard and work at Google.”

Recalling the process of writing about her experience, Nietfeld explained she was inspired by Marya Hornbacher, author of “Wasted: A Memoir of Anorexia and Bulimia.” Hornbacher was also from Minnesota, also suffered from an eating disorder as a teenager and was even treated in the same hospital and treatment center as Nietfeld.

“Her book was very detailed [about having] an eating disorder,” she said. “We were just in the same spaces. It’s just such a specific perspective, to be coming from that younger voice.”

In the interview, Nietfeld mentioned she received a letter from a reader in a similar predicament: The reader’s parent was a hoarder and the young woman had also been put into treatment while preparing for a college application. That kind of feedback made Nietfield feel writing her memoir was worth it.

“I’m writing about things that happened to me when I was a teenager and that are happening to other teenagers all the time,” she said.

Toward the end of “Acceptance,” Nietfeld questions the idea of redemption: “I had to take tragedy and twist it into triumph. Otherwise, I would be pathetic,” she writes.

But she believes stories about flaws and weaknesses are just as valuable.

“Teenagers are humans, too,” she noted.

She gripped the tea she had ordered earlier, and turned to look at the street. New Yorkers passing by the coffee shop didn’t rush on this clear fall afternoon. Neither did Nietfeld. As our long conversation wound down about her past self, she reflected, “It can be messy figuring it out.”

Great story!