BY STEPHEN DiLAURO | If you were around the Village and Soho at the end of the 1970s, chances are you remember SAMO© and the mysterious messages that began appearing everywhere, with that tag.

“Samo was an experiment in hype,” says Al Diaz. “Though I doubt we were capable back then of expressing it that way. We were hyping a product that didn’t exist.”

The “we” he refers to are his 19-year-old self and the late Jean-Michel Basquiat — Diaz’s then-17-year-old partner in SAMO©.

SAMO© the “product” was the guilt-free religion from a short story Basquiat wrote for the school newspaper at the experimental high school where Diaz and Basquiat first met as students.

“We did not mean it as ‘Same Old Shit,’” Diaz says. That explanation of the tag was foisted upon the public in a Village Voice article by Philip Faflick, published in December 1978. Faflick paid $100 to the two youths behind SAMO© for their story.

“Once it came out that we were two teenagers, I figured that was it,” says Diaz. For him the mystery and mystique were bound to dissipate. For Basquiat, however, it was his first taste of fame, and he wanted and got more.

“He started telling people he was SAMO. Soon, we went our separate ways,” says Diaz. They remained friends, but at a distance.

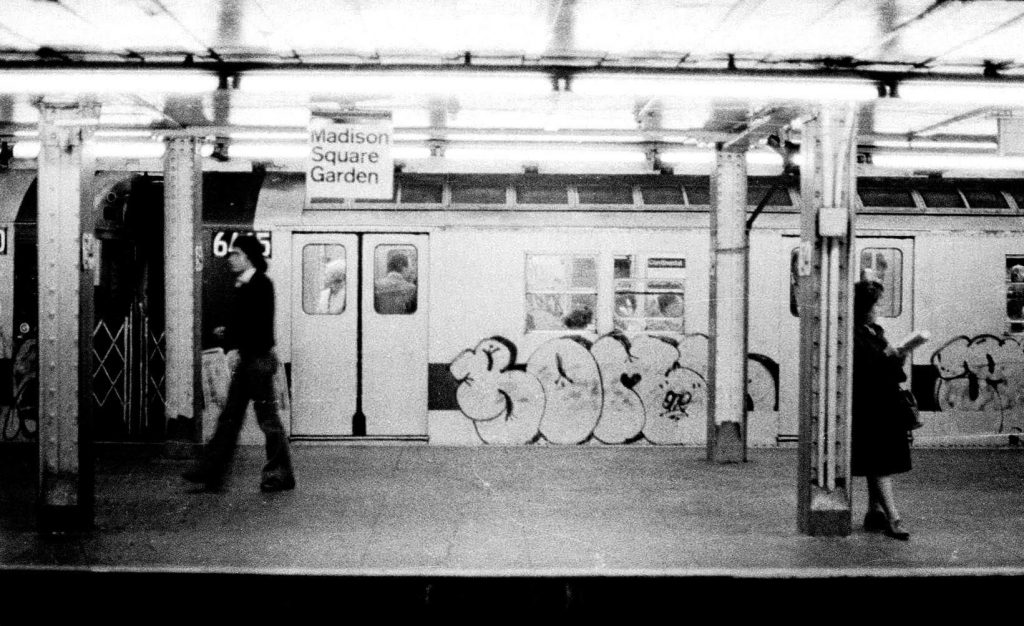

Before there was SAMO©, there was BOMB1. That was the tag Diaz used for his graffiti from age 12 to 16 or 17. He grew up in the Jacob Riis Houses development on Avenue D in the East Village. But it was while visiting relatives in Washington Heights that he became enamored of big, colorful, bold tagging. It was as BOMB1 that he introduced street art to Basquiat, who was from Brooklyn.

Diaz says his political philosophy, as such, was forged in the time and place where he was raised.

“’Question authority’ was a big thing then,” he recalls. “I mean, why wouldn’t you question authority?”

As happens every 10 years, one decade morphed into the next and the 1970s became the 1980s. The East Village began to boom as a new mecca for artists and gallerists. Graffiti and street artists began to find galleries that appreciated and displayed their work. The mainstream media began to glorify investment bankers and Wall Street greed. Junk bonds were all the rage and made Michael Milken very rich, even if he did go to prison. Gentrification became an unstoppable force Downtown. Rents soared.

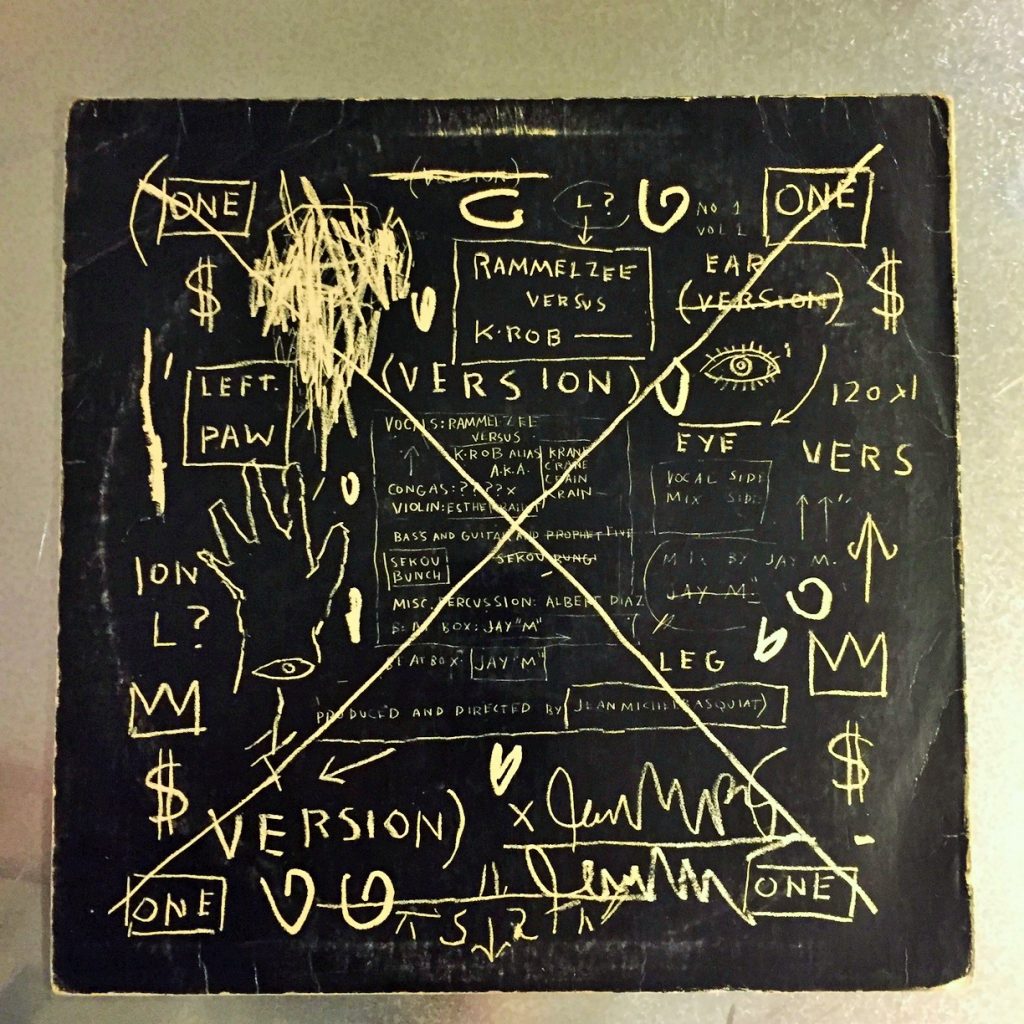

It was in the early ’80s that Diaz and Basquiat did their last collaborative effort — a musical offering titled “Beat Bop.” It was a 12-inch vinyl single of a song by hip hop artists Rammellzee (who eventually also gained acclaim for his visual art) and K-Rob. Basquiat produced the record and Diaz played all the percussion on the recording.

In 2017, Rolling Stone named “Beat Bop” one of the 100 best hip hop recordings of all time. The original pressings had cover art by Basquiat. Extant copies of that record are, as one might imagine, very collectible.

As Basquiat’s artistic reputation grew, he dropped the references to SAMO© and reverted to his given name. Then, suddenly, he was dead of an overdose.

Al Diaz, meanwhile, maintained a low profile. Then, in the new millennium, political discourse in America descended into the obfuscation, disinformation, misinformation and nonsense that persists to this day. Diaz decided it was time to resurrect SAMO©.

His elegant coffee table book “SAMO©. . . Writings: 1978 – 2018” is available through his Web site (www.al-diaz.com). It presents the story of the early years with Basquiat, profuse with illustrations, as well as documenting many of his more recent SAMO creations. His works on canvas are available through Van der Plas Gallery on Orchard Street on the Lower East Side.

For many, Diaz is an éminence grise in the world of street art. He is a prominent element of the international touring art show “Beyond the Streets,” which is billed as “the premier exhibition of mark makers and rule breakers.”

The work, both past and present, is represented in the book in all its literary glory. Closer to haiku (or text messaging or tweeting) than either abstract or representational painting, Diaz’s efforts are in demand across the United States. His installations, both public and private, can be found from Hollywood, California, to New Mexico to Miami, Florida, and far-flung places beyond the shores of this troubled nation. Diaz is as much a littérateur as he is a visual artist.

A recent SAMO© mural in an East Village community park was tagged and obliterated by members of a new generation of graffiti street artists. Diaz seemed unfazed by the whole thing.

“There are a couple of entire generations who have no idea who or what Samo is,” he shrugs.

Other artists from the neighborhood quickly transformed the tags into a message: “Respect Samo.”

Let’s add to that: SAMO© 4ever!!!

DiLauro is a playwright, critic and musician.

Be First to Comment