BY KAREN KRAMER | Longtime Village resident Adam Zucker has worked on some very powerful documentaries as an editor. But it is his latest documentary, “American Muslim” — which he produced, directed, shot and edited himself — that will have reverberations way beyond the confines of a movie screen.

A native New Yorker who grew up in Flushing, Zucker went to college in Binghamton (where he studied film and art). After graduating, he returned to live in New York, first in a loft in Tribeca, followed by a stint in the Meatpacking District, and finally to his home at Morton and Greenwich Sts., where he has lived for more than two decades

For many years he has had a successful career as a film editor, working on influential documentaries. However, it was the election of 2016 that stirred something in him that he couldn’t ignore.

“Like most people I know, I was pretty upset during the presidential campaign of 2016 with all the bigotry and hatred and vilifying people,” he said. “And when the election happened, I was just devastated. I had no idea what to do. I was just talking to everyone I met.”

He soon realized that “just talking” wasn’t enough when he learned that some New York communities were direct targets of this bigotry.

“About a week after the election I was invited to a Muslim/Jewish sharing circle at a shul,” he recalled. “There were mostly Jewish people but someone got up from the Muslim community and started talking about some of the terrible things that were already being experienced in her community.”

That person was Debbie Almontaser a prominent educator and activist. Almontaser’s Yemeni-American community had been hit particularly hard and her stories about anti-Muslim actions made a strong impact on Zucker.

“Debbie mentioned people in Queens who had their apartment leafletted with words like, ‘This is Trump country now’ and immigrant women wearing their hijab being accosted on the street. At that moment I said, ‘I really have to do something.’ Bigotry has always been present but it’s coming out in ways it never did before and it’s all because of Trump.”

It seemed obvious to Zucker to want to use his art and craft of filmmaking as an educational and organizing tool. But at first he wasn’t sure what the process would be.

“I didn’t necessarily think it was going to be a feature documentary,” he noted. “I thought maybe I would make some short films for the Web or do an advocacy film for an organization — which, in fact, I did. I did a couple of those films for people along the way. I didn’t even know where the films would go but I needed to contribute in some way.”

Thus began a two-year mission to bring his film “American Muslim” to fruition. And what started out as short advocacy pieces for the Web slowly turned into a feature documentary.

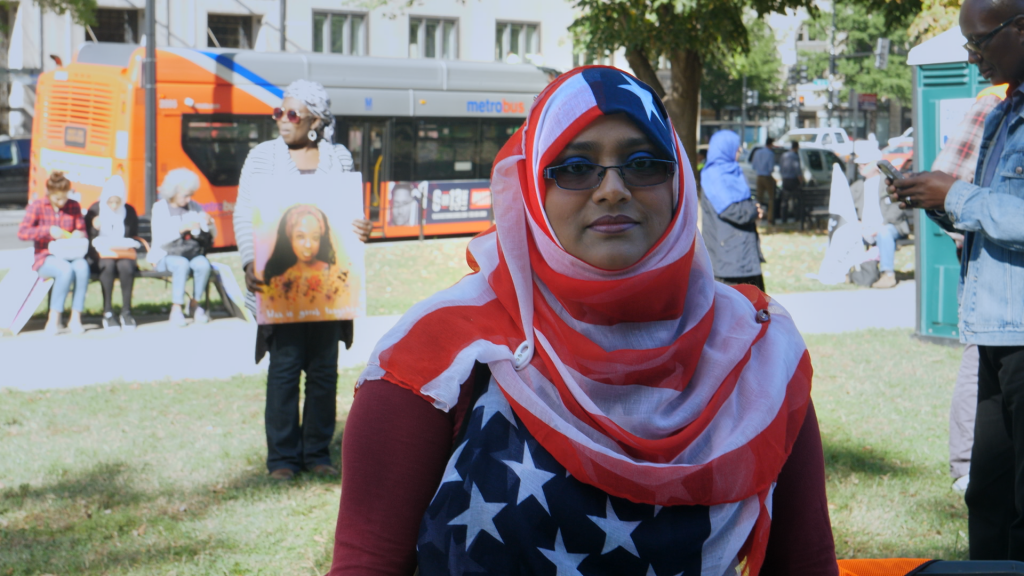

At the beginning of the project, he filmed a lot of pro-immigration rallies that started to happen after Muslims were put on Trump’s anti-immigrant list.

“I gave my footage to whoever wanted it, I did that all along the way,” he said. “But I wanted to film other things for the documentary. Those demonstrations — as important as they are media-wise — were not going to be an important part of my film. Because what audiences really connect with is people. And I went and I listened and I talked to people.”

Someone steered him to a group in Brooklyn called Muslims Giving Back, started by a dynamic young Algerian-American named Mohamed (“Mo”) Bahi. Determined to bring the best of the Muslim community to a wider neighborhood, the group has a monthly food drive for their Asian and Latino neighbors. Bahi also oversees weekly food pantries and Saturday night expeditions to feed the homeless, as well as running the first emergency women’s shelter in New York City.

Zucker contacted Bahi to learn what he was doing and eventually to ask him to be part of the film. The trust was immediate.

“He wanted me to film his activities and I wanted to film them,” Zucker said.

Bahi also spearheads Project Transform, which selects one immigrant family each month to help, often with housing. In one of the film’s more moving scenes, Bahi raises money from the community to help furnish an apartment — right down to the very details of wall hangings — for an immigrant family that otherwise would have nothing. When his wife complains about making too many holes in the wall to hang the pictures, Mo wryly jokes, “These people are from Syria. They know about having holes in the walls.”

“What became clear to me,” Zucker said, “as I was working on the film is I knew about Islam but I didn’t know any people well, and I hadn’t really been to a mosque except as a tourist when I was abroad in Turkey or Morocco. So for me going to the mosque and hanging out and talking to more people was eye-opening.

“And I realized that when I would talk about this project with friends and colleagues, many other people were in the same situation. They certainly supported the rights of Muslim-Americans and were unhappy about what was going on, but they didn’t really have any direct contact.”

Another individual in the film is Imam Shampi Ali, an Indonesian world figure who has written a book with a rabbi.

“He’s very committed to interfaith, as are other people,” Zucker said. “He told me he was going to Temple Emanu-El, and I filmed him doing a workshop there. He brings school groups there and even some school kids from Indonesia, who then meet with Jewish kids.

“A group of people from the synagogue would meet with a group of Indonesians students,” the filmmaker continued. “First, they would have dinner and then they would share. Jewish students were asked to bring in ritual objects and share what the meaning was. When a Jewish student brought in a prayer shawl and discussed its meaning, an Indonesian student mentioned they had something similar.

“Ali tells the students, ‘When you go back to Indonesia, I want you to tell your friends that there are people like this in America that are really interested in sharing and your job is to be ambassadors.’ So that’s interfaith.”

Greenwich Village is also represented in the film. The Islamic center at New York University, on Thompson St., is a progressive, open center that also works with community outreach and interfaith.

“The Friday night after the election, members of Congregation Beth Simchat Torah came to Islamic Center N.Y.U. and greeted Muslim worshipers as they were coming to their prayers,” Zucker noted. “They came there and handed people flowers as they entered. I filmed the greeters, as they’re known, twice over a couple of months. The Muslims attending services still talk about how meaningful these greeters were.”

Zucker feels that his Jewish background helped to heighten his sensitivity to oppressed people. He belongs to a progressive synagogue, The New Shul, where services are held in different venues around Greenwich Village.

“In my own synagogue, the New Shul, our rabbi brought an imam in to speak once for a Friday night service that was the largest service we ever had,” he recalled. “Everyone wanted to meet the imam.”

And for Zucker, the outreach will continue.

“What I have is the American Muslim Interfaith Project,” he explained. “It’s basically bringing together synagogues and mosques and church groups for a joint screening [of the film] at one of their community’s locations, followed by a discussion led by people in each of the communities. And after the screening, hopefully, to have dinner at the place and to continue talking.

“My mission is to open up the eyes of non-Muslims,” he said. “And it needn’t be faith based; it’s just that that’s a convenient way to go about it. I’d be just as interested if I was doing intercommunity work. I literally want to bring people together and talk about misconceptions and get them to know each other a little bit better.”

For December, Shampi Ali has invited the Union Temple of Park Slope to a center in Manhattan. And that same evening, members of The New Shul are going to the Muslim Community Center in Sunset Park, where Mohammed Bahi is hosting a screening of the film for his community, followed by a talk.

Although for the moment, these events are limited to members of the congregations, there will be others in the future that welcome the public. Please check the film’s Web site (www.AmericanMuslimFilm.com) for screenings. Other community groups that are interested in using the film can also contact Adam Zucker through that site.

“Hopefully, other areas outside of New York, where it is perhaps more necessary, will follow,” he offered. “There are interfaith activities going on everywhere. I really wanted to make a film that would open a window into a world.”

Be First to Comment