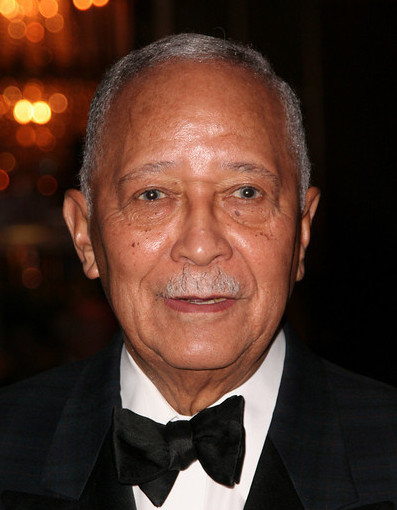

BY TOM FOX | I was saddened to hear of Mayor David Dinkins recent passing but certain that he is resting in peace with his beloved wife Joyce. Many New Yorkers are probably not aware of the critical role Mayor Dinkins played in the creation of the Hudson River Park and I appreciate this opportunity to recognize his contribution publicly.

I first met then-Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins when we were appointed to the West Side Task Force in July 1986 after the city and state withdrew the Westway proposal. A federal judge found that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers misrepresented data regarding the impact its project would have on the Hudson River’s striped bass and other marine life. That resulted in the judge’s barring any landfill until new studies were done, which effectively ended the Army Corps’ plans to landfill the Hudson River from Chambers St. to West 36th St.

A 22-member task force chaired by Arthur Levitt Jr., then chairperson of the American Stock Exchange, consisted of many important New Yorkers, such as Herb Sturz, chairperson of the New York City Planning Commission; Sandy Frucher, president of the Battery Park City Authority and former secretary to Governor Mario Cuomo; Mayor Koch’s Deputy Mayor Rob Esnard; M.T.A. board member Ronay Menshel; city and state Department of Transportation commissioners; labor leaders; business people; Borough President Dinkins, and four citizens.

Our primary assignment was to recommend a replacement roadway configuration for a new West Side Highway. We all agreed that it was important to have meaningful community participation since top-down planning had killed Westway.

After a five-month public planning process, task force members decided that the replacement roadway should be an at-grade boulevard built on the existing West St. right-of-way, which eliminated the need for the landfill in the Hudson that had killed Westway. Landfill was taken off the table and that decision reserved for a future entity.

The city and state wanted that entity to be a development authority with a small board, controlled by the governor and the mayor. A number of agencies and institutions would be required to implement whatever replacement roadway was recommended, and all the task force members agreed that these efforts should be coordinated; but we didn’t agree on the governance structure of the new entity.

Dinkins argued that, as an elected official with considerable responsibility for the future of the area, the Manhattan borough president should have appointments to any new body. He also insisted that citizen appointments be required, and that mandatory public participation was essential to the success of the project.

The final compromise was to recommend a planning entity whose board included appointments made by the governor, mayor and Manhattan borough president and that several of the appointees must be citizens. The task force also recommended that any new entity be required to follow existing city and state land-use review procedures, including all public-review requirements.

However, in January 1987, the night before the recommendations were to be released, the task force was at an impasse. Three of the citizen members refused to approve the recommendations unless a publicly financed waterfront esplanade, that had been agreed to but reneged on by the city and state, was included. A number of pro-development task force members were adamantly against public funding for an esplanade. They understood that a public esplanade, that opened the waterfront to local communities for the first time in 200 years, would seriously reduce the probability of future real estate development on landfill or platforms — or both — out in the Hudson River. At the time, Sandy Frucher proposed filling in 90 acres between Chambers and Canal Sts. to expand Battery Park City.

However, citizen members felt strongly that the esplanade needed to be included in the recommendations for them to sign on. After all, we were all Westway opponents who were just a token representation of everyone who couldn’t be at the table and we needed to fulfill our responsibilities. Our chairperson, Arthur Levitt Jr., wanted a consensus recommendation.

The logjam held tight until the night before the recommendations were to be released, when David Dinkins said, “If the citizen members won’t sign on without the esplanade, neither will I.” By siding with the people, he insured that the public esplanade, which was the first element of the future Hudson River Park, was included in the final task force recommendations the next morning. Those recommendations were accepted by the city and state.

We served together again on the West Side Waterfront Panel, chaired by Michael del Giudice, for which Borough President Dinkins and his staff helped craft a “Vision for a Hudson River Waterfront Park.” The panel recommended that landfill and platforms be prohibited, along with residential, commercial office and hotel use outboard of the highway. Another new entity was recommended to oversee the creation of the proposed waterfront park, but a major obstacle to moving forward with the project was a lack of funding.

At the end of 1991, the state and city were crafting a memorandum of understanding (M.O.U.) to establish the new entity to oversee the park’s creation and secure the required funding. These were incredibly tight times for public funding; many city and state services, especially parks, were experiencing serious reductions in their operating budgets. However, David was now Mayor Dinkins and he far exceeded park advocates’ early hopes when he signed the M.O.U. creating the Hudson River Park Conservancy (the predecessor to the Trust) and included $100 million in the city’s 10-year capital plan for the park’s construction.

Governor Mario Cuomo however, was more reluctant to commit scarce state resources and announced that his $100 million match would come from a $1.9 billion Environmental Quality Bond Act that he placed on the ballot in 1992. However, that initiative was rejected by voters and the state didn’t commit to match the city’s funding for the park until 1996.

Mayor Dinkins’s support for the Hudson River Park, insistence on a public waterfront esplanade and community participation, and his $100 million commitment toward construction of the park were catalysts in creating what is now the 21st-century equivalent of Central Park for Manhattan.

The park remains a work in progress. But without David Dinkins there wouldn’t be this $1.3 billion waterfront park that has created new recreational and open-space opportunities for local communities, enhanced our sustainability, the image of our city and our quality of life.

May he rest in peace.

Fox was a member of the West Side Task Force and West Side Waterfront Panel, the first president of the Hudson River Park Conservancy (which completed the Hudson River Park’s general project plan), a founding board member of Friends of Hudson River Park from 1999-2011, and a current member of the Hudson River Park Advisory Council. Fox is currently writing a first-person history of the Hudson River Park, to be published by Rutgers University Press and scheduled for release late in 2021.

If only David Dinkins had been as thoughtful with TOMPKINS SQUARE PARK.

Mt memory of Dinkins is his paving the way for the Giuliani administrations, his dividing the city against itself and his facilitating the gentrification to come.

As the city’s first Black mayor, he evicted homeless encampments all over the city, including outside of the New York Coliseum (now “Time Warner Center”), the base of the Manhattan Bridge and Tompkins Square Park.

I’ll always remember Mayor-elect Dinkins sending his two lackeys Michael Karfen and Bill Lynch to Tompkins where they ASSURED the homeless that they could winterize their tents because there would be NO removal from the park. They also told the homeless that their anarchist supporters who had been getting them food and supplies and had fought off attempts at evicting them, were using the homeless for their political ends — a pathetic attempt at dividing us.

Sure enough, a week or so after Dinkins’s lackeys’ visit, on the coldest day of the year in December 1989, an army of kops, led by Captain Savage (his REAL name), raided Tompkins Square Park. The homeless, angered over Dinkins’s betrayal, burned their tents and belongings in protest.

A famous moment that day was homeless man Terry Taylor holding a mirror to Savage and his goons.