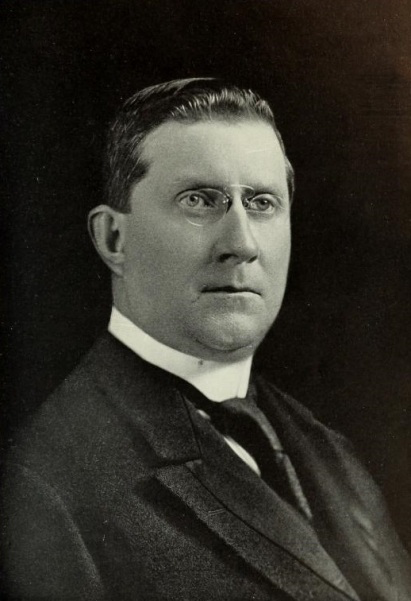

BY THOMAS F. COMISKEY | When Charles Francis Murphy was born in 1858, his Irish immigrant parents could never have imagined that their second of eight offspring would one day hold court in Delmonico’s restaurant as the kingmaker in New York City, State and even national politics.

The future Tammany Hall boss’s political progeny are credited with introducing unprecedented labor and social reforms in the early 20th century. But Charles F. Murphy a.k.a. “Silent Charlie” began his life in dire poverty in the Gas House District, one of the city’s worst slums. A male growing up in this predominantly Irish and German neighborhood — concentrated in the teens and 20s blocks bordering the East River — was typically condemned to an unhealthy childhood followed by an abbreviated life of backbreaking labor.

Growing up Gas House

“The gas-house district is not a pleasant place in the daytime, much less at night,” warned a 1907 article in The Outlook magazine. Charles F. Murphy’s tenement at 322 E. 21st St. was in the 18th Ward, a befouled neighborhood where Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village arose after World War II. It was a run-of-the-mill pre-Civil War tenement, with no hot water or bathrooms. Toilets were in outhouses behind the building.

In their book “Astor,” Anderson Cooper and Katherine Howe depict the overcrowded tenement blocks of Murphy’s era. An apartment had two rooms: One was for cooking and washing, and could be used as a workroom for garment piecework or cigar rolling. It measured 8 feet by 10 feet. The sleeping room measured 7 feet by 8 feet. Total room space: 136 square feet. The halls were 3 feet wide. The two rooms may have held two or three families at a time, and there were six to eight apartments per floor. Waves of immigrants poured into the same squalid buildings. Until the adaptation of steam-shovel technology around 1870, unyielding bedrock blocked new housing development in central and northern Manhattan.

When young Charlie Murphy left his building to step out into the street, things only got worse. Sewers were uncommon in the 1860s. Animal manure and garbage clogged the curbside gutters. In 1863, Manhattan had the highest death rate in the world: 1 in 35. By contrast, the death rate in the United States in 2021, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, was 1 in 119.

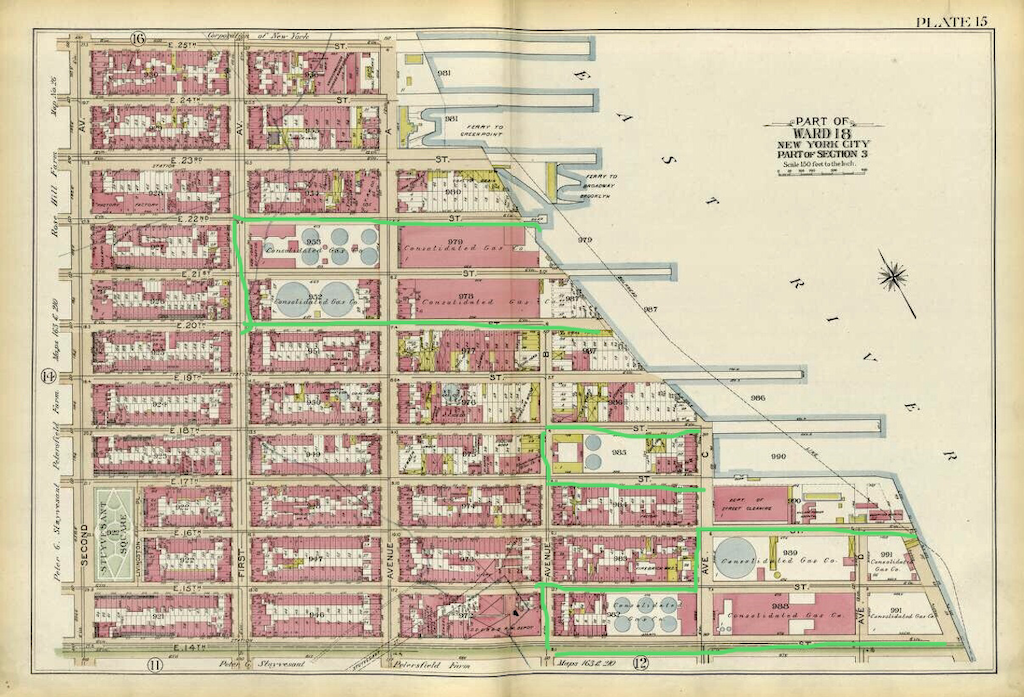

And then there was the gas. As the 1894 City Atlas depicts, Consolidated Gas Company’s gas works (marked in green, below) dominated the district along the East River from E. 14th Street to E. 22nd Street.

The gas company blasted crushed coal with steam to produce gas for Manhattan’s streetlights. Giant smokestacks pumped into the surrounding blocks the noxious chemical byproducts, including carbon monoxide, methane and carbon dioxide. Dr. H.M. Field observed in a report on sanitary conditions in the 18th Ward in 1865, “The ground all about a gasometer is as barren of trees and verdure as a desert of sand.”

City sanitary inspector Dr. Elisha Harris testified in February 1869 that when the fluid mixture was exposed to the atmosphere, it gave off deadly gases and sulfide of ammonium, which “may float far over the city, so far as to become dangerous to health to a great distance.” According to one writer, “It was a neighborhood of potent ugliness, a wasteland of rubble and rust strewn with monstrous gas tanks, and belching gas works.” Murphy’s tenement was across the street from massive gas tanks and gas works that covered four square blocks. The oldest gas tanks were on 22nd and 21st Streets, and they leaked.

The path to power

Although Charles F. Murphy was baptized in the Church of the Immaculate Conception, at 505 E. 14th St. (the Murphys once lived at 503 E. 15th St.), he attended Mass every Sunday at the Church of the Epiphany on E. 22nd Street, which became known as the “Tammany Church.” He left school at 14 and began a prospective career of manual labor, first at a local wire factory, and then as a caulker at America’s largest shipbuilder, John Roach & Son, on the East River at 10th Street.

In 1875, Murphy took the reins of a horse-drawn streetcar that wound its way from the East River at 23rd Street, south on Avenue A to 18th Street, west to Broadway, south to 14th Street, then west to the Hoboken ferry. He also took a part time job as a handyman in the saloon of former Republican Assemblyman and Kips Bay District Leader Bernard “Barney” Biglin.

Murphy first displayed his leadership and organizational skills in 1876. Recruiting his Gas House friends and co-workers, he formed a social and athletic fraternity, the Sylvan Club, and a baseball team, the Senators, of which he was captain. Charlie Murphy’s Senators toured the state, winning stakes in town after town. Murphy, an athletic catcher, received offers from professional baseball teams.

By 1880, Murphy had saved $500, and he leased a saloon at Avenue A and 19th Street. He called it Charlie’s Place. Murphy situated the Sylvan Club on the floor above his saloon. Poor immigrants regarded saloons as much more than a place to drink. They were the social and political center of the neighborhood, and the bartender was a confidant and leader. At Charlie’s Place, gas house workers, stevedores, shipyard laborers and politicians paid a nickel for a schooner (15 ounces) of beer and a cup of soup. Though he drank little, Charlie was an observant and solicitous bartender. Murphy refused to serve women, in part because so many saloons that did were promoting prostitution. He also banned swearing in the bar.

Charlie’s Place did well, and Murphy opened two more of what he called his “poor man’s clubs,” including one at 20th Street and Second Avenue, where the local Tammany Hall Democrat branch, the Anawanda Club, settled on the second floor. Another Murphy saloon, The Borough, at Lexington Avenue and 27th Street, was an elegant, posh establishment geographically and socially more aligned with the Kips Bay neighborhood than the Gas House District.

Gas House vs. Kips Bay

Rowing was a very popular spectator sport in the second half of the 19th century. Thousands cheered from the riverbanks, betting on their favorite oarsmen. The winners became celebrities. Barney Biglin and his brothers — sons of Irish immigrants — won dozens of big-stakes races and were popular culture heroes. In 1872, the great portrait artist Thomas Eakins painted “The Biglin Brothers Racing.” It hangs in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Barney Biglin cashed in his pop star status for a political career. He was a district leader and state assemblyman for the Republican Kips Bay neighborhood, which bordered the north end of the Democrats’ Gas House District. Barney’s Republican godfather was Chester A. Arthur, collector for the Port of New York Customs House. After the Civil War, the “spoils system” at the Republican federal level was the equivalent of the Democratic Tammany patronage machine at the municipal level. New York customs income was the largest source of federal revenue. Chester A. Arthur awarded Barney Biglin two jobs in the Customs House, plus a decades-long contract to collect and deliver immigrants’ luggage after they arrived at Castle Garden. Immigrants complained that some of their luggage was “lost” after Biglin’s hired hands took custody.

In the fall of 1880, Republican presidential nominee James A. Garfield was running with Chester A. Arthur for vice president. A political “grudge” match was arranged: Gas House election district captain Charlie Murphy’s Democratic Sylvan Club oarsmen versus Kips Bay Republican district leader — and rowing legend — Barney Biglin and his brothers. The Sylvan Club’s rowing team was drawn from muscular immigrant shipyard workers.

Gas House laborers and residents bet heavily on the Sylvan Club. The rival crews met on the East River at 100th Street. Fervent fans rubbernecked north to 129th Street. Then the word spread quickly: The Sylvan Club stroke was too sick to row — and he claimed he was drugged. Fights erupted among Sylvan and Biglin supporters. The Biglins proposed they row over the course to win by forfeit. English journalist Maurice Low reported a riot was “imminent.”

“Just when the prospect was blackest, Murphy stepped down to the river bank,” Low wrote. “He took off his hat, coat, and collar, handed them to a friend, and calmly took his place as stroke of the Sylvan boat.” Sylvan fans “began to bet again for their men, taking all the money the Biglin crowd could rake and scrape together.” Murphy set a steady cadence from the start, matching the Biglins stroke for stroke. Near the finish line Murphy added a powerful surge and the Sylvan crew was victorious.

That night, Murphy rode on the shoulders of ecstatic immigrants around the Gas House District.

“He had won the day, and by winning it saved thousands of dollars for the poor men who had wagered on his crew,” The New York Times said. Thanks to Charlie, Tammany Hall triumphed. Charlie Murphy was a hero, and his political and economic future was limitless.

Taking on the Tammany Tiger

In 1883, the Tammany Hall Democratic machine refused to endorse Charlie Murphy’s friend Assemblyman Edward Hagan for reelection. Murphy told Hagan to run as an independent, and Murphy managed and financed his victorious campaign. Murphy’s support was also crucial to the winning campaign of Gas House District Leader Francis Spinola for Congress in 1885. That same year, Tammany Hall located its 18th District political organization, the Anawanda Club, on the floor above Murphy’s saloon at 20th Street and Second Avenue. In 1892, Murphy became the Anawanda Club’s district leader and joined Tammany Hall’s executive committee.

Silence is golden

Charles F. Murphy was a man of so few words that friends, colleagues and journalists couldn’t stop talking about it. His reputation for reticence may have begun when he became district leader. Every night Murphy stood under a gas lamp outside of his saloon at 20th Street and Second Avenue, where constituents approached with their requests. Conversations with Mr. Murphy were brief. The petitioner spoke for a minute or two, followed by a yes or no nod by Mr. Murphy. Local politicians from the Anawanda Club stood nearby, ready to turn Murphy’s yes into reality.

Murphy left no records, no correspondence and no formal speeches. His interviews, few and far between, were inconsequential. “Never write when you can speak; never speak when you can nod; never nod when you can blink,” Murphy advised. If asked for the time, Murphy would pull out his pocket watch and display it. When he became the Gas House district leader, Murphy negotiated face to face, by telephone or through intermediaries. Murphy always remembered what he promised, and what was promised to him.

Murphy’s aversion to verbosity was epitomized at a Fourth of July celebration at Tammany Hall. Two thousand people were on their feet, singing the national anthem — except for Silent Charlie Murphy. A journalist asked Tammany secretary Tom Smith, “What’s the matter with the Boss? Can’t he sing?” With a wink, Smith replied, “Of course he can. Perhaps he didn’t care to commit himself.”

Friends with benefits

In 1897, Tammany boss Richard Croker’s mayor, Robert Van Wyck, appointed Charles F. Murphy to the Dock Commission. Murphy served only for four years. But for the rest of his life, Murphy was addressed as either “commissioner” or “Mr.,” the latter a title reserved for just one other person in New York at the time: John J. McGraw, the legendary manager of the New York baseball Giants.

In 1901, Murphy, his brother, John, and two friends from the Anawanda Club opened the New York Contracting and Trucking Corporation (NYCT). Soon the city leased docks to NYCT at bargain basement prices. NYCT then sublet those docks to shipping companies for huge profits. After obtaining contracts for excavation work on West Side subway lines, NYCT was able to use their piers and dumping privileges to get rid of their own rubble and be paid for it.The city Board of Aldermen blocked the building permits for Penn Station and its tunnels, until NYCT was awarded a $2 million construction contract. NYCT’s bid was $400,000 higher than the low bidder. By 1905, NYCT and its subsidiaries had garnered $15 million in city government contracts.

The ownership of a large number of NYCT stock shares was never revealed. In 1905, future Supreme Court Justice Charles Evan Hughes led an investigation into New York utility companies. Charles F. Murphy swore at a hearing that he did not own any NYCT stock.

In the four years that Charles Murphy was a dock commissioner, his personal wealth grew from the $400,000 he saved during 18 years of running saloons to at least $1 million. When Boss Murphy died, his estate was worth $2 million. He had expanded his country home at Hampton Bays from 50 to 500 acres, including 1,000 feet of bay frontage. He owned 14 properties in Manhattan, including his residence at 305 E. 17th St., a four-story brownstone overlooking Stuyvesant Square Park. He also owned 301 E. 17th St., 228 E. 21st St., an entire blockfront on the west side of Lexington Avenue from 26th to 27th Streets, 82 and 86 Lexington Ave., 127 to 131 E. 26th St. and 151 E. 18th St.

The Boss

In September 1902, Charles F. Murphy was elected the new leader of the Tammany Hall Democratic machine, and he held that position until his death, 22 years later. Located on E. 14th Street between Third Avenue and Irving Place, Tammany Hall was the headquarters for the 35-member executive committee of the New York County Democrats. The Tammany leader, or “boss,” was an unsalaried, non-public position who wielded power while the Democrats controlled city and state government. The executive committee members could be, and often were, gamblers, former prizefighters or criminals banded together into a political party to enrich themselves.

Before Charles F. Murphy became its leader, Tammany Hall was synonymous with organized municipal corruption, thanks in part to the thievery of boss William M. Tweed. The infamous boss died in prison after leading a conspiracy that embezzled millions of dollars in public funds from 1868 to 1871. Murphy’s predecessor, Boss Richard Croker, retired to his mansion in Oxfordshire, England, with his millions after allegations arose that he extorted bribes from whorehouses, gambling halls and illegal bars in return for protection from police.

In his 20 years as Tammany boss, Richard Croker never elected a governor. Charles F. Murphy elected three governors, three mayors, two United States senators and numerous state legislators.

Two of the finest politicians Murphy placed in power were Robert F. Wagner, Sr. and Alfred E. Smith. Wagner served as the majority leader of the State Senate, lieutenant governor and a New York State Supreme Court judge. In 1926, Wagner was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he was crucial to the implementation of New Deal legislation.

Al Smith served 10 years in the State Legislature, was president of the city’s Board of Aldermen and a four-term governor. Al Smith’s governorship was noted for social and political reform, and his nonpartisan appointment of highly qualified administrators.

“I shall be asking you for things, Al,” Boss Murphy once told Smith. “If I ever ask you to do anything which you think would impair your record as a great governor, just tell me so and that will be the end of it.”

If he had lived, Murphy might have elected Al Smith to the presidency.

Legacy

Three days after Charles Francis Murphy died a century ago on April 25, 1924, the city and state’s political elite packed Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. Outside, more than 50,000 mourners assembled to pay their respects to Mr. Murphy — the biggest funeral turnout since the death of President Ulysses S. Grant. Quite an outpouring for a taciturn man who held a single public position more than 20 years prior to his passing.

Murphy cited his separation of Tammany Hall from the New York Police Department as one of his most significant accomplishments. The police had long been recipients of kickbacks, payoffs and bribes from the city’s vice trade, which Murphy despised. In red light districts, like the Lower East Side and the Tenderloin, where prostitution and gambling flourished in saloons, opium dens and brothels, those payments inevitably made their way into the hands of district leaders and local elected officials. Under prior Tammany regimes, police officials had worked for and contributed money to Tammany tickets. In return they received Tammany’s support for promotions, transfers, light duty — or political and legal protection when they broke the law. Murphy urged the appointment of non-Tammany police commissioners and reform mayors.

Like Tammany bosses who preceded him, Murphy issued handouts to his working-class constituents: turkeys and clambakes, coal in winter, ice in summer. When civil service tests were instituted to curtail the patronage power of political bosses, instead of fighting reform, Murphy directed his district leaders to organize classes so that their constituents would pass the exams. But after the horrific 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory fire left 146 garment workers dead, Murphy knew that handouts and patronage jobs no longer cut the mustard.

While Murphy was no progressive ideologue, he did know that good policy was good politics. Growing up in the Gas House District instilled empathy in Murphy for the working class. Nancy J. Weiss argued in her masterwork, “Charles Francis Murphy, 1858 to 1924: Respectability and Responsibility in Tammany Politics,” that Murphy’s greatest contribution was unprecedented in Tammany history: Murphy nurtured and placed into office a group of young men who governed responsibly. With Murphy’s power and support, these men became mayors, governors, senators and congressmen. They enacted and administered dozens of pieces of social and economic legislation that advanced factory safety, restricted child labor, reduced working hours, created workers’ compensation, provided widows’ pensions and regulated tenements.

When Murphy concluded that the 19th Amendment would succeed and give women the right to vote, he directed his men in the State Legislature to support its passage. And then he made certain that women were integrated into the city’s district executive committees. In 1920, Tammany included a female delegate-at-large in its convention attendees.

Murphy’s support of reforms crucial to the welfare of his immigrant constituency transformed Tammany Hall into a political organization that secured the votes of the massive waves of new immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. And these laws served as a blueprint for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration when America was driven to its knees during the Great Depression.

Thomas F. Comiskey is the author of “The East Village Mafia,” which reveals the previously unknown, 70-year Mafia stronghold in the blocks just south of East 14th Street.

Wow! What a history! This is such a revelation!