BY HARRY PINCUS | Just recently, I was telling my son about how current events remind me of my own political awakenings, more than 50 years ago.

I was talking to him about the days when I first read Malcolm X and Richard Wright, took an active part in the shutdown of Hunter College, and worked the graveyard shift, loading trucks from midnight until eight in the morning at the F.D.R. Station Post Office on E. 55th Street.

I’d started out there as a sorter and only lasted a day or two doing that. The sorter was leaned up on something called a “posture bar” and expected to continuously stuff envelopes into cubbyholes.

You could not sit and you could not stand. You could not speak, and you certainly could not listen to music. Most of all, the poor sorter could not stop. If you did happen to cease for so much as a discernible instant, a nasty, sagged-out old man called a supervisor came along and reminded you of your utter lack of human rights.

As I was not hesitant to express my disdain, they soon transferred me to the loading docks, where I was tasked with feeding the splintered guts of the 18-wheelers with mailbags that weighed more than I did.

It was summer, the miasmic heat bled onto the loading bays at night, and they worked us until we collapsed onto the rough wooden skids.

I was young and strong, though, and I felt free. There was a rhythm to the loading, and an honest pride to the hard work. The foreman even allowed for an occasional transistor radio, and we could bop along to Mungo Jerry’s hit “In the Summertime.”

Across the street was the legendary P.J. Clarke’s bar, a vestigial stub of the old Third Avenue, famed for the elevated subway and Ray Milland’s dive in the 1945 film “The Lost Weekend.”

Some of that old New York still existed in the summer of 1970, when I was 17 years old. But when I took lunch at 4 a.m., the avenue was populated by what Lou Reed called “the wild side.” Just getting an egg salad sandwich at Smiler’s required navigating around invitations for sex acts I’d never even heard of.

I had an hour for lunch, an hour to watch as hustlers looked for tricks, lovers kissed in doorways, and garbage trucks hauled off the remnants of another summer’s day. I dreamt of who I would love, and who I would be, and then I went back to the steamy docks to haul the endless sacks of mail.

Some of the old-timers were beaten down by the drudgery, like the guy who pushed a linen cart around all night and wore a Martian headdress made out of clothes hangers. He made crazy sounds, clicked out jazzy riffs, and never said a word to anyone.

My favorite was the night watchman, a great man named Arthur Hackey. We used to gather around his broken office chair in hopes that he would feel up to spinning a tale or two, because his yarns were golden. He told us about his life as a Black man in America, what it was really like back in the Thirties, and all of the twists and turns that had befallen him since.

He offered up advice about women, and spoke of artists and communists in Harlem, back in the day. Of buying weed from Mezz — “y’know, Mezz Mezzrow, the Reefer Man” — a Russian Jew who insisted he was Black, and played clarinet and sax with the great Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet.

Hackey had also been involved in the fight game, and was working the corner for the “Old Mongoose,” Archie Moore, on the night when young Cassius Clay gave the ancient warrior a whupping. The sage old champion had been Clay’s mentor, but now he was superannuated, though ageless and legendary. According to Hackey, “The fight was fixed. But it didn’t have to be.”

Like my father, Hackey’s convictions were borne of hard experience. He didn’t hate America, he just saw it from its underbelly. For men like Hackey and my father, the only way out was the dream of socialism.

Hackey created a good atmosphere around the loading docks, where it was easy enough for tempers to flare as the foreman bore down on us to move even more mail. The situation grew even hotter when a large, shirtless white man, with the broken nose of a fighter, joined the line and began spewing the mailbags at a select few.

This big Southern heavyweight alighted upon me, the Jewish kid, and started tossing mailbags at my head. The sweaty beast was speeding up the line for everyone, and one day, at “lunch,” surrounded by vending machines, I announced that I could take it no more. The crew listened to me and kind of snickered into their sandwiches. But I was shaking and terrified as I returned to the docks. What would I do? What could I do?

When the line started up again, it wasn’t five minutes before a massive sack of mail came hurtling at my head. The line stopped, and I stopped. I knew I had to confront him, now. All of the actors stood in place, beneath an upper deck with handrails and more sacks of mail.

It was high noon, all-night style, as I stood there in my leather work gloves, facing my adversary. I could feel my heart pounding, beads of sweat pouring down my neck. The air that I was pulling into my lungs was constricted and hot.

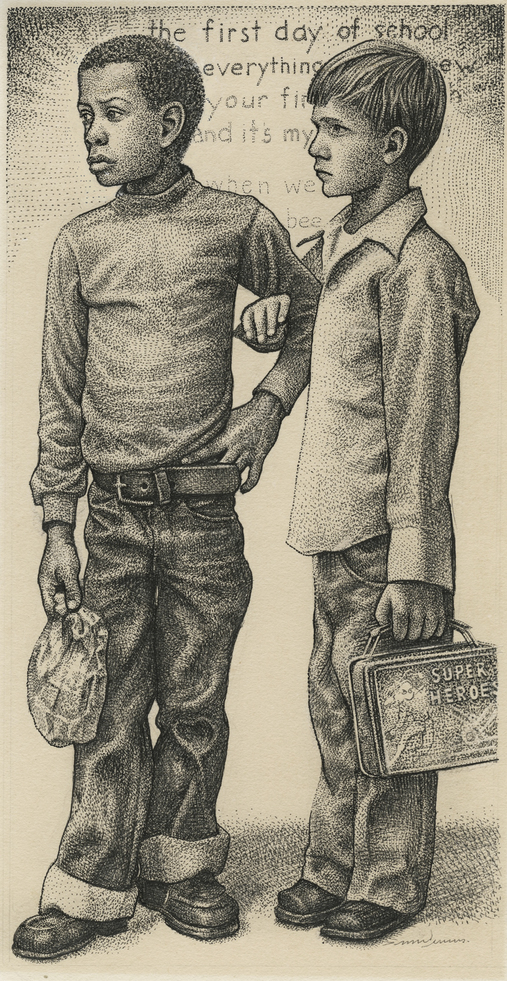

Suddenly, an enormous mailbag, easily weighing more than a hundred pounds, came flying down from the upper deck. It landed with the proverbial thud at the foot of the sweaty beast, brushing by his face and nearly decapitating him. All of the actors looked up at the gallery, and there was my friend Bill. Beautiful Bill, a young black middleweight, shirtless and powerful, glistening and laughing. Bill pounding a fist into his glove.

“Sorry,” he said, looking down with glee upon the Monster. “It was a accident.”

One night I met Hackey at the Lexington Avenue subway station, and he invited me to join him in a cab ride to the post office.

“I’m a poor man,” he said, apologetically, “and I hate to take a cab. But I just can’t make it anymore.”

Perhaps he was looking at the scruffy growth of hair I was trying to raise on my face. Because somewhere along the way, my friend allowed that it was his ambition to grow a beard, as he put it, “just once in my life.”

Toward the end of the summer, Hackey stopped coming to work. It was time to go back to school, and we couldn’t just leave the old post office without a proper farewell.

As the morning sun rose on our final labors, and droves of office workers poured out of the subway holes, another young worker and I decided to visit Hackey. We marched all the way down to a hand-scrawled address for a tenement building on Ninth Street and Avenue A, but when we rang the bell, there was no answer.

After a few minutes, a woman came out on her way to work, I guess, and we asked about our friend.

“Oh, Hackey?” she said, her eyes alight with pleasure. “You mean, Hackey.”

Then the light left her face. She told us that we had just missed him. He had died a few days ago.

“I don’t know what happened,” she said. “He was tired, and then he stopped coming out, your know. He was growing a beard, you know.”

So many things have changed in these 50 years, and yet so many things remain the same. We seem to cling more fiercely than ever to our tribes, our sense of entitlement and our fears.

When I look at things as they were before 9/11, the world seems naive. It was a place where people still seemed to work for a collective future and not just our own narrow self-interests.

Perhaps the loss of our innocence, the rise of our cynicism and the demise of the future arrived in that one fell swoop, when the daggers cut down our crown.

I know that my friend Hackey would never have given up on the future. That’s why he was bothering to teach us, and that’s why he was growing a beard. The summer was over, and I returned to school, but I was a man now.

Pincus is an award-winning illustrator and longtime Soho resident.

Superb, in every way. Thank you, Mr. Pincus.

Great story! Thank you for sharing. Love the drawing!